Democratic presidential candidate Andrew Yang is putting his money where his mouth is: He’s giving families $1,000 a month to promote his proposal for a universal basic income — a recurring, government-funded stipend for all American adults with no strings attached.

The 44-year-old New York City entrepreneur turned presidential hopeful will distribute $1,000 of his personal fortune to one family in Iowa and one in New Hampshire — the first two states on the presidential caucus and primary calendar — every month this year to prove the efficacy of his so-called Freedom Dividend.

“This would enable all Americans to pay their bills, educate themselves, start businesses, be more creative, stay healthy, relocate for work, spend time with their children, take care of loved ones, and have a real stake in the future,”

Yang says on his campaign website.

A handful of countries including India, Canada, and most recently, Finland, have experimented with versions of a universal basic income (UBI), which some studies show help boost an economy and allow workers to find better jobs. Preliminary results from Finland’s nationwide test show that it did not lead to gains in employment, but did improve beneficiaries’ health and well being.

Andrew Yang pushing universal basic income

“On the basis of an analysis of register data on an annual level, we can say that during the first year of the experiment the recipients of a basic income were no better or worse than the control group at finding employment in the open labour market,” said Ohto Kanninen, Research Coordinator at the Labour Institute for Economic Research.

But the handout reduced recipients’ stress levels. “The recipients of a basic income had less stress symptoms as well as less difficulties to concentrate and less health problems than the control group. They were also more confident in their future and in their ability to influence societal issues,” said Minna Ylikanno, Lead Researcher at social services agency Kela.

In the U.S., the Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration, or SEED, this month will begin testing a program in Stockton, California, that distributes $500 a month to approximately 100 residents — making it the first American city to experiment with free money.

A UBI at the level Yang proposes would expand the U.S. economy by 12.6 percent to 13.2 percent — or $2.5 trillion by 2025 — and would increase the labor force by 4.5 million to 4.7 million people, according to the Roosevelt Institute.

“The most direct and concrete way for the government to improve your life is to send you a check for $1,000 every month and let you spend it in whatever manner will benefit you the most. The government is not capable of a lot of things, but it is capable of sending large numbers of checks to large numbers of people promptly and reliably,” Yang says on his website.

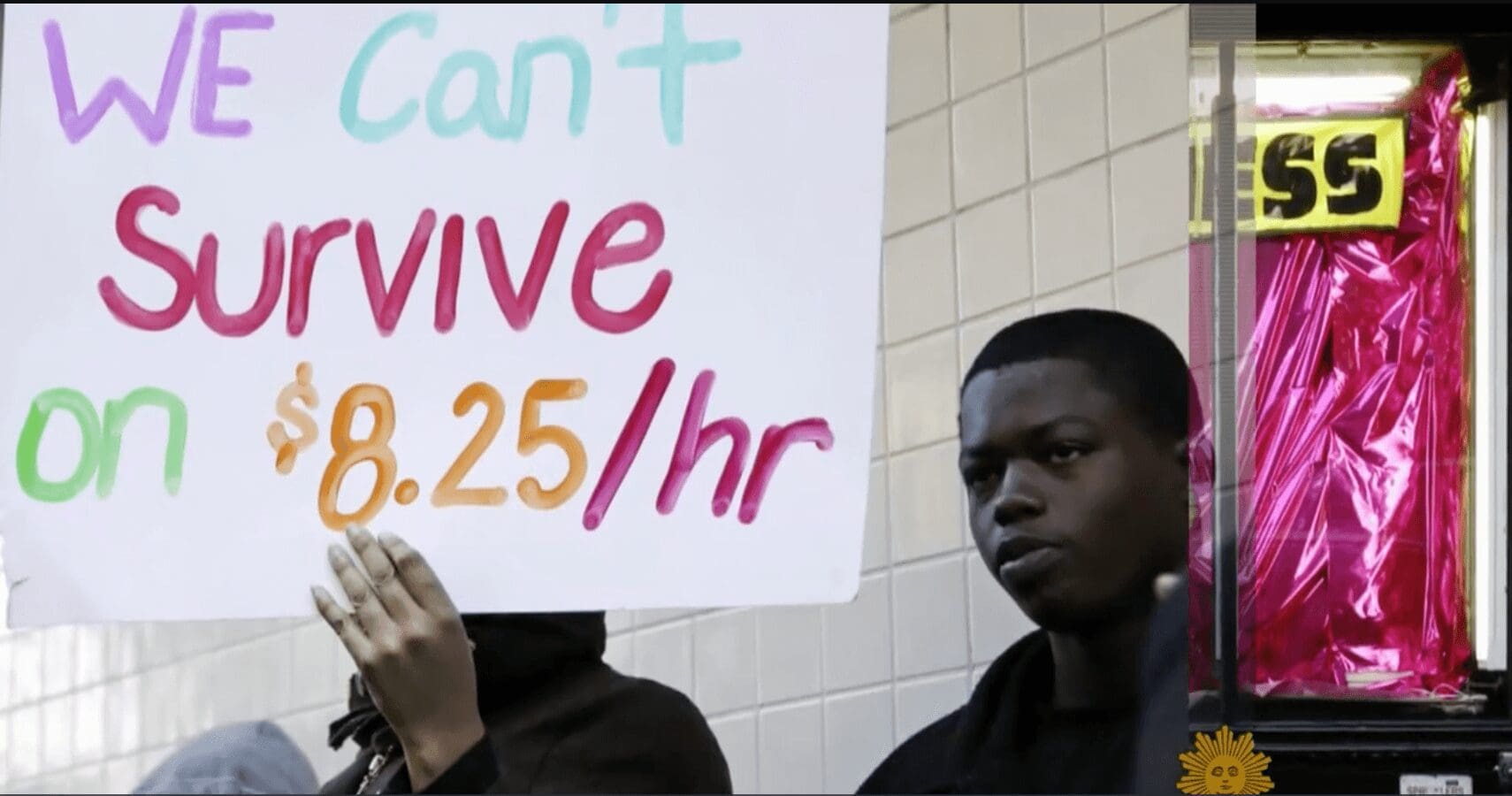

Putting money in Americans’ pockets

Yang cites advances in technology — automation is expected to displace one-third of American workers by 2030 — as the main force behind the idea. He also said putting money directly into the pockets of American consumers will “turbo-charge” the consumer economy.

The Fassi family in Goffstown, New Hampshire, was selected from a pool of applicants to receive the first handout, Fox News reported. They’re two months into the experiment, while an Iowa family has yet to be selected, according to the report.

Yang said his UBI would be funded by a 10 percent value-added tax, or VAT, on the production of goods and services that would generate $800 billion in revenue.

Self-defeating?

But critics of the funding mechanism argue that it would disproportionately burden low-income families. Marshall Steinbaum, one of the authors of the Roosevelt Institute report, said a regressive VAT would work in direct opposition to a UBI’s goal.

Stockton mayor on universal basic income

“If the point of the universal basic income is to rectify wage stagnation, poverty, or to have some sort of response to rising inequality, that’s great. But if we pay for it with a VAT, you undo all of those gains because you’re causing poor people to pay for this, which undermines the argument for why we need a UBI to begin with,” he told CBS MoneyWatch.

Instead, he thinks taking on government debt would be a better way to fund the program. “It’s much more expansionary if you have the government take on debt to pay for it,” he said, “because then you have transferred household debt to the government.”

First published on February 12, 2019 / 12:29 PM

© 2019 CBS Interactive Inc.. All Rights Reserved.