Red tape, fraud-prevention efforts, and overwhelmed agencies left many Americans without benefits.

By: Shawn Donnan and Reade Pickert

Barb Ashbrook, who lost her part-time job at a food court in downtown Indianapolis in March 2020, was denied unemployment benefits because she was earning more than $121 a week from a second job at a Dollar Tree store. Ray Rand, laid off by an RV rental company in Las Vegas, was rejected after missing a 48-hour deadline to respond to an inquiry while in the hospital. Anthony Barela, an Albuquerque barber, spent months trying to find out why he didn’t get benefits.

They’re three of at least 9 million Americans thrown out of work by the pandemic who didn’t receive any unemployment benefits despite the largest deployment of economic aid in U.S. history, according to a Bloomberg Businessweek estimate based on a review of more than a year’s worth of U.S. Department of Labor data. That’s a hole in the safety net as big as the population of Virginia.

Now, as the U.S. reopens, unemployment assistance has become the focus of a political debate. Critics say the programs enacted during the pandemic may be undermining the recovery by discouraging jobless Americans from looking for work—an argument challenged by many labor economists and top White House advisers.

More than half the states, almost all with Republican governors, have announced they will stop paying a $300-a-week federal supplement before it’s set to expire in September. A majority of those are also ending a program created for workers not previously eligible for unemployment insurance.

The controversy has deferred a frank assessment of the system that will remain: an 85-year-old New Deal creation that proved woefully inadequate in an emergency.

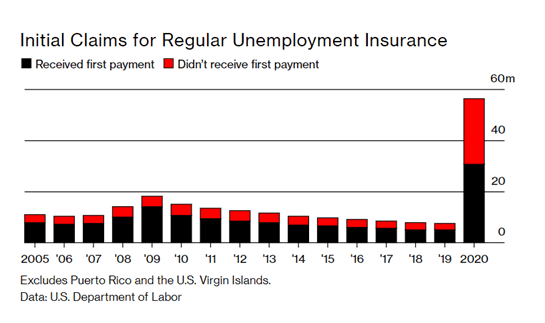

Half the 64.3 million people who sought help through the regular unemployment program from March 1, 2020, through March 31, 2021, were rejected or not paid, the data show. That’s twice the rate during the Great Recession.

Many of them then applied for Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), a program designed by Congress to provide a cushion for gig workers and the self-employed, only to be turned down for that as well.

To be sure, the scale of the help has been remarkable. About 49 million workers—30% of the U.S. labor force—received at least one weekly payment, according to the data. More than $750 billion in unemployment benefits has been paid by the U.S. Treasury, compared with $28 billion in 2019. Yet this crisis has illustrated the system’s frailties, including aging IT infrastructure, understaffed state agencies, and often arbitrary rules.

The data also highlight stark differences among states. California paid more than 70% of claims for regular unemployment during the 13 months beginning in March 2020, while Montana didn’t pay benefits to 89% of those who applied. The maximum payment ranges from $235 a week in Mississippi to $855 in Massachusetts. Almost all states offer 26 weeks of benefits in normal times, though in Alabama the limit is 14 weeks. “Depending on where you live when you lose your job, you either have a program that will help you bridge to your next job or you’re in danger of losing your apartment,” says Rebecca Dixon, executive director at the National Employment Law Project, a research and advocacy group.

The data are as messy and uneven as the system itself, complicated by the way states report their numbers and what officials say have been millions of cases of suspected fraud. Florida hasn’t filed monthly reports about payments for the PUA program since September 2020, a lapse state officials won’t explain. In Nevada officials say their PUA figures are inflated by 1 million suspected fraud cases, but the state has reported just one fraud payout in that program, worth $3,108, to the U.S. Department of Labor.

“The unemployment system is broken,” says Senator Ron Wyden, the Oregon Democrat who chairs the Senate Finance Committee and is leading a push for more generous benefits, a wider eligibility pool, and automatic adjustments in hard times. Before the pandemic, Wyden says, “state after state sabotaged their unemployment system by making benefits as hard as possible to access.”

A spokesperson for the Labor Department said in an email that the new programs created by Congress greatly expanded coverage. But he acknowledged that an unprecedented increase in new claims, coupled with low administrative funding, a fragmented system of state programs, limits on eligibility, and a wave of fraud, contributed to the large number of people “who weathered the pandemic without the aid of unemployment benefits.”

In Indiana, 1 in 3 people who applied for unemployment didn’t receive any help. Among the denied was Ashbrook. The 64-year-old, who lives alone, had cobbled together a variety of part-time jobs in the Indianapolis area. When the lockdown hit, she was logging 16 to 20 hours a week as a $9-an-hour customer service representative at Dollar Tree and about as many hours for similar pay as a cashier at the food court in an office building downtown. Aramark, the company that operated the food court, laid her off in March 2020.

She applied for unemployment, hoping to take advantage of provisions designed to fill in for lost income. But her application was rejected. “They told me I couldn’t get unemployment because I was making more than $120 a week at Dollar Tree,” Ashbrook says. Under Indiana’s rules, earning more from a part-time job than you would get in benefits disqualifies you for any help for lost income.

That meant she couldn’t access the $121 in regular unemployment benefits each week she might have been entitled to or the $600 weekly federal top-up. She didn’t appeal or apply for PUA, believing she wasn’t eligible. Then in August, $5,892 turned up in her bank account. A month later an additional $900 landed. Recognizing what she thought was a cruel mistake, she sent $4,000 in money orders back to the state. In November, Indiana officials acknowledged the error and she was forced into a repayment plan for the rest that’s haunted her since. After a payment went missing in the mail in March, the state threatened to garnish her wages and tax refunds. “I didn’t get anything out of the deal, and I ended up owing money,” she says. She’s turned to the courts to try to have what by mid-June was $1,700 in debt forgiven, but she hasn’t succeeded. A spokesman for Indiana’s labor department declined to comment about the case.

Jennifer Terry, Ashbrook’s lawyer at Indiana Legal Services, a nonprofit that provides free assistance to low-income state residents, says the case isn’t unusual. More than a year into the pandemic, she and her colleagues are still working through hundreds of requests for help from people denied benefits retroactively by state officials. That’s often because employers objected to claims months after they were filed, saying workers left voluntarily or declined to return. Terry says businesses have an incentive to do that because their unemployment insurance premiums are determined in part by how many claims laid-off employees file.

The federal government doesn’t track denial rates for unemployment benefits. To establish how the system performed during the pandemic, Bloomberg Businessweek examined data filed by states, including the number of claims and those receiving first payments for regular unemployment and PUA.

This was supplemented by public information obtained from states and in response to queries.

The number of people not paid is incomplete and likely higher than the 9 million estimate. The analysis excluded Arizona and Pennsylvania because of data distortions. Arizona reported receiving more than 4 million PUA applications despite having a workforce of 3.6 million people. Officials there blamed fraud, the extent of which they say they’re still trying to determine. Officials in Pennsylvania said the incomplete statistics reflected how the crisis had strained the system.

Available data on fraud illustrate the opaqueness of the system. Many states can’t say how extensive it is and haven’t reported numbers to the federal government. The U.S. Department of Labor’s inspector general estimates potential fraud could be worth “tens of billions of dollars.” States by the end of March had reported paying out less than $2 billion in fraudulent claims since the start of 2020.

But there’s also evidence that innocent people have been caught up in efforts to clamp down on fraud. Federal data show officials in Nevada made payments on only one-tenth of applications for PUA in the program’s first 13 months. Nevada says the number of applicants is inflated by fraud, but lawyers say the state has used the label too liberally. “They just deny, deny, deny,” says Mark Thierman, a Reno lawyer leading a lawsuit on behalf of gig workers denied benefits that’s before the Nevada Supreme Court. “Their definition of fraud is they disagree with you.”

One plaintiff is Rand, 53, who lost his main income when tourists vanished from Las Vegas and the company where he was an IT consultant closed. He was denied regular unemployment benefits and applied for PUA that May. He was approved for $240 a week, but the money didn’t turn up. Then in January he was denied benefits altogether after missing a deadline to respond to an inquiry.

This month his fortunes shifted. On June 18, more than a year after he filed his claim, $12,876 landed in his bank account. He also got a job as a computer technician for the local school district. By then, Rand, who lives alone, had sold his Kia Sedona and other belongings. He eked out a living on food stamps, rental assistance, and stimulus payments, stressing over a possible eviction. His credit report is ruined, and he owes money to the IRS. “It’s been hell,” he says.

For some, the assistance arrived too late. Ralph Wyncoop, a former bus driver who moved to Las Vegas a few years ago to drive for Uber, applied for PUA benefits as soon as Nevada began accepting applications in May 2020. He’d already lost two months of income and been rejected for regular unemployment. He was told he was eligible for $455 a week backdated to March 15 based on his income history. When the money didn’t come through, he joined Thierman’s lawsuit.

In July, Wyncoop’s PUA application was rejected. Officials said they couldn’t confirm his identity even though he submitted copies of his driver’s license, Social Security card, Veteran ID, a car insurance bill, and tax returns. Leah Jones, one of his lawyers, says Wyncoop was told he needed to present a utility bill. It was something he couldn’t provide, Jones says, because his landlord paid for utilities.

Wyncoop’s health deteriorated. He had a heart attack late last summer and was hospitalized. In October he was evicted from his bungalow for failing to pay rent. He began sleeping in his car. “I have no idea why I was denied and cannot reach anyone to clear up my problem,” Wyncoop wrote to the state labor department. “By not paying me what I am entitled to under the CARES ACT, I am now homeless, bankrupt, and in declining health daily. Please Help Me.”

Wyncoop finally started receiving benefits the day before Christmas, after a judge found the state in contempt of an order to speed up payments to an estimated 100,000 PUA recipients like him. By then his health had worsened. He was found dead in a motel on March 17, almost a year after he first applied for unemployment.

The Nevada labor department said in an email that its decisions were based on federal guidance. “These guidelines ensure that people eligible for benefits are paid and those that are not eligible are not paid,” a spokeswoman wrote. Officials declined to comment on individual cases, citing privacy laws.

A plan pushed by Wyden and Colorado Senator Michael Bennet, a fellow Democrat, would set base unemployment benefits at 75% of lost pay compared with the roughly 45% that’s the norm now. It would establish federal benefits for anyone looking for work, create a permanent stopgap scheme akin to the PUA, and increase benefits automatically in times of economic turmoil. The Department of Labor said the crisis illustrated the need for widespread reform of the unemployment system, something President Joe Biden has called for.

Delays in payments and denials have led to lawsuits in states including Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Oregon, and Virginia. Their success has been limited.

In Oregon and Virginia, court-approved settlements required officials only to speed up efforts to clear backlogs. The lawsuits have done little to address the holes in personal finances and damaged credit scores many of those denied benefits are confronting.

Barela, a plaintiff in the New Mexico case, had to quit working as a barber when the state locked down last year. Like many in his profession, Barela rented a chair in a barbershop, which made him a contractor. More than a year later, he’s still trying to recover from the state’s refusal to approve him for any benefits.

He spent months trying to get someone to explain why he was rejected for PUA, a program set up to help contractors like him. Once he was on hold for four hours, waiting to speak with a supervisor, Barela says. “He said: ‘Well, we’re not going to help you. You’re not going to get any help from us. Don’t call back.’ And then they hung up on me.” Lawyers for the state said in a written response to the lawsuit that they didn’t have enough “identifying information” to comment on Barela’s circumstances.

To support his fiancée and the three school-age kids they have between them, Barela worked nights at a UPS warehouse and afternoons at a Container Store outlet for a few months starting last October. He’s back cutting hair in Albuquerque, but this time as an employee instead of as a contractor, earning $10.50 an hour.

Barela says he has some sympathy for those who describe unemployment as a generous handout keeping people out of the workforce. But he also feels ignored. “I’ve heard a lot of people speak and say that they’re making more money than they would when they’re working in their jobs,” Barela says. “But then I see people in my situation who really needed the money.”

Methodology

To figure out how many Americans fell through the cracks of the unemployment system, Bloomberg Businessweek used state and federal data to calculate the difference between the number of claims filed over a 13-month period and the number of people who received first payments, both for regular unemployment insurance and the new Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA) program. After consulting with federal and state officials, as well as independent experts, we used three different methods to calculate the number of applicants in each state who weren’t paid. We defaulted to the lowest number to arrive at the estimate of at least 9 million. Arizona and Pennsylvania were excluded from the analysis because of questions about the quality of their submitted data. While it’s not possible at this time to determine the extent to which initial claim numbers have been inflated by fraud, our estimate is below the more than 16 million people U.S. Department of Labor data show didn’t receive any payments after filing claims for PUA, which has been the main target of scammers.

______________________________________________________________

Original post can be found at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/features/2021-06-23/can-outdoor-dining-fix-its-accessibility-problems