It’s not uncommon in the United States for two parents to spend long hours working hard — but the one who works outside the home is paid for it, while the one who does housework and child care is paid nothing.

Now, several Democratic presidential candidates are proposing that parents who stay home to care for children be paid, too. It’s a twist on typical family policies — like paid leave, subsidized child care or the right to work part-time — all of which make it easier for parents to have jobs outside the home. Instead, this proposal would make it easier for them not to.

It’s an idea that blurs partisan lines. On the left, there have long been calls to recognize the economic value of unpaid domestic labor by paying for it. At the same time, many on the left fear that paying at-home parents — who are most often women — would reinforce unequal gender roles and set women back in the labor force.

“The question is: What do we mean by work?” Andrew Yang said on The Daily last month, and gave as an example his wife, who stays home with their sons.

On the right, proponents appreciate that the proposal supports traditional families and allows young children to be home with a parent. Yet many on the right resist the expansion of government benefits, especially without work requirements.

The tax code already tends to favor couples with a single earner over dual-earner couples who earn similar incomes. But the other ways the tax system helps parents require that they work outside the home. Two are tax credits aimed at families with children: the earned-income tax credit for low earners, and the child tax credit, which is given to most families. Two others are for buying child care: the child and dependent care credit, and dependent care flexible spending accounts.

Democratic presidential candidates have proposed some type of payment that would benefit at-home caregivers of young children and other relatives.

“The question is: What do we mean by work?” Andrew Yang said on The Daily last month, and gave as an example his wife, who stays home with their sons. “I know my wife is working harder than I am, and I’m running for president. And right now, the market values her work at zero. So we have to think bigger about what we mean by work and value.”

Cory Booker and Julian Castro have focused on poor families, proposing to expand the earned-income tax credit to include at-home caregivers — essentially eliminating the tax credit’s work requirement for people who are doing unpaid care work.

Others have proposed sending a monthly check to parents for any caregiving needs, as Canada, Australia and most European countries do (or, in Mr. Yang’s case, sending a check to every American). Six of the senators running for president support the idea: Michael Bennet, Kamala Harris, Amy Klobuchar, Bernie Sanders, Elizabeth Warren and Mr. Booker.

They are co-sponsors of the American Family Act of 2019, introduced by Senator Bennet. It would send all but the highest-earning families $300 a month for each child up to age 5, and $250 for each child 6 to 16. People who don’t work for pay would be eligible — in contrast with the existing child tax credit — and it would be paid monthly, not just at tax time.

“Caregiving is the most meaningful work a parent can do, but for some reason, we’ve made it harder and harder on families,” Mr. Bennet said. The proposal would “give parents the opportunity to make decisions that are best for their families,” he said.

Mr. Booker included this “child allowance” and the expanded tax credit in a plan he presented on Thursday to reduce child poverty.

Other candidates, including Ms. Warren and Mr. Sanders, also want to create a Social Security credit for people who take time out of the work force to care for family, “to compensate the more than 43 million unpaid family caregivers for their work,” according to Mr. Sanders’s campaign. (Ms. Warren, in her 2003 book, “The Two-Income Trap,” proposed giving at-home parents a subsidy, though she did not include that in her 2020 campaign plan for subsidized child care and preschool.)

The general idea behind the proposals is that children need care — and families take a financial hit to provide it, whether they buy child care or stop working. Child care costs have been rising, and in many places it’s difficult to find high-quality care.

Also, more than half of Americans say they believe young children should have a parent at home, and more than half of mothers say they would prefer to stay home (even though most parents work).

Most of the Democratic candidates have proposed some form of subsidized child care or public preschool, and some say that a corresponding subsidy for at-home caregivers would allow parents to choose who cares for their children. (President Trump made a similar proposal when he was running for president, but did not include it in his tax plan.)

But they’re also acknowledging something else: Often, staying home is not really a choice at all. If parents’ jobs are too inflexible to accommodate children’s needs, or pay too little to afford child care, taking care of their child has to come first.

As long as people have debated the idea, there has been disagreement over whether paying women for unpaid labor is liberating or oppressive.

In the United States in the late 1800s, Charlotte Perkins Gilman, the writer and social reformer, wrote that unpaid labor took away women’s independence and ought to be done by paid experts. Around the same time, the United States for a period paid single mothers a pension, on the belief that it was best for children if mothers did not work outside the home (though black women were largely excluded).

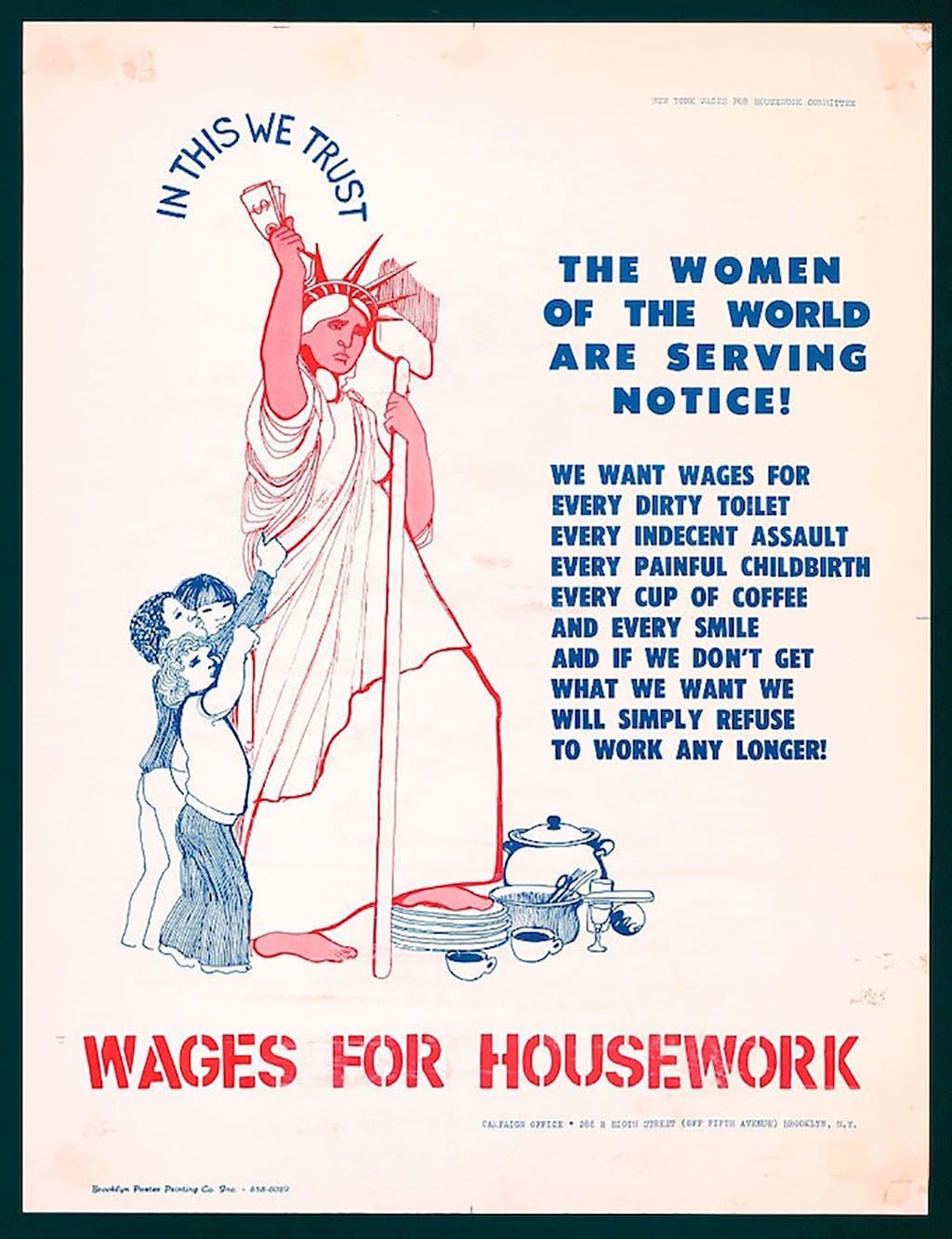

The idea resurfaced during the feminist movement of the 1970s. That period is well known for the rush of women into the work force. But there was a parallel movement, which began in Europe and spread to the United States: wages for housework. The argument was that women should be paid for the work they were already doing, and that men’s paid work depended on it, as Louise Toupin described in a history of the movement last year.

Similar debates continue today in countries that pay a child allowance. In Finland, for example, the policy is seen as giving women “freedom to choose,” while in Sweden, it has been called a “trap for women.” (The policies are usually gender-neutral, but it’s mostly women who use them.)

In the United States, some critics of the idea say that if more mothers took breaks from outside work, it could erase their gains in the labor force and stall progress toward sharing labor at home.

“Without strong incentives for dads to take on some of those duties, this would simultaneously cement women’s second-class place in the work force and perpetuate men’s second-class place in family life,” said Stephanie Coontz, the director of research and public education at the Council on Contemporary Families.

Class and race complicate the issue. Historically, African-American women have always been expected to work, and federal benefits for poor families increasingly include work requirements.

Family policies can have different effects on children and parents, said Chris Herbst, an associate professor of public affairs at Arizona State University. Research is clear on the benefits of high-quality care for children from low-income families. But he found that work requirements can result in worse outcomes and lower-quality care for children. Other research has found that for children from richer families, the benefits of child care were smaller.

A popular policy would be one that all parents could use, said Kimberly J. Morgan, a political scientist at George Washington University who has studied the politics of family policies internationally. Societies that value caregiving have policies that assist parents who work outside the home (like paid leave and subsidized child care) as well as parents whose work is at home.

The more widely appealing message, she said, would be: “It’s not just supporting working mothers, but it’s about investing in children broadly.”

Claire Cain Miller writes about gender, families and the future of work for The Upshot. She joined The Times in 2008 and was part of a team that won a Pulitzer Prize in 2018 for public service for reporting on workplace sexual harassment issues.