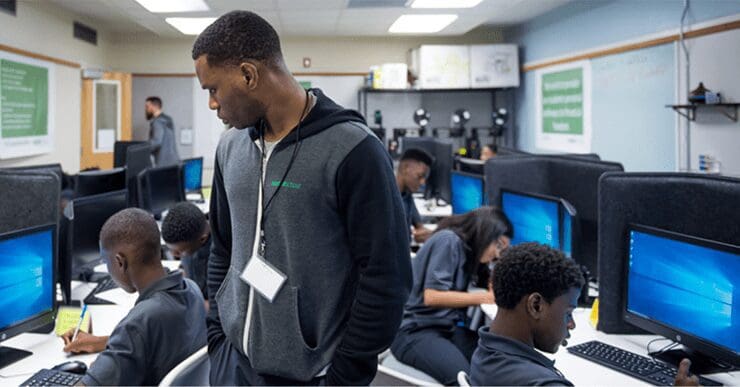

Could $50 a Week Empower High School Students to Set and Meet Education Goals? This New Orleans School Aims to Find Out

By: BETH HAWKINS

Amid the steepest economic decline in recorded U.S. history, there is renewed interest in the concept of universal basic income — cash payments to low-income families. Now, with no end to the pandemic yet in sight, a New Orleans high school is poised to carry out a first-of-its-kind small-scale pilot to see whether modest grants to seniors will boost their prospects.

Launched three years ago with the goal of closing the Black-white wealth gap in its students’ lifetimes, Rooted School hopes to give 52 weekly transfers of $50 via a cash app to 10 members of the Class of 2021, starting in September. In partnership with the New Orleans education innovation incubator 4.0 Schools, which is funding the grants and the study of their effectiveness, Rooted’s leaders hope to hire two university researchers to track its results.

The micro-pilot has a goal of graduating students from high school with the job skills to guarantee the economic stability to enable them to stay in college.

“We want to ask the question, could cash transfers in the high school setting improve the lives of the people we’re trying to serve?” says Hassan Hassan, CEO of 4.0. “Having access to a guaranteed transfer every week for a year — how does that affect stress? Academic achievement?”

While cash transfers can take several forms, the central concept is to provide a financial floor. Given the certainty that money will be available on a specific date, people will spend it on things that improve their quality of life and help them climb out of poverty.

In May, Santa Clara County, which surrounds San Jose, California, announced it would provide $1,000 a month to 23-to-25-year-olds transitioning out of foster care. Stockton, in the heart of California’s Central Valley, is in its second year of a mayoral initiative to provide $500 a month to 125 residents for 18 months and study how the money is used.

Hassan and Rooted founder Jonathan Johnson want to hire the researchers who are tracking the Stockton experiment to monitor the high school’s micro-pilot, as they are calling it. Both are experts in cash transfers; Stacia Martin-West is an assistant professor at the University of Tennessee College of Social Work, while Amy Castro Baker is on the faculty of the University of Pennsylvania’s School of Social Policy and Practice.

The decision to start with a handful of students and a modest amount of cash stems from past research that showed that even small grants of $500 a month can have unintended consequences, such as boosting a family’s income just enough that its members no longer qualify for health care or housing subsidies, but not enough to replace those benefits.

Although critics of universal basic income worry that recipients will use the money for frivolous or even harmful things, for the most part researchers have found that the purchases are for basic necessities.

“It’s proven that when you invest directly in people who live in poverty, they make the best decisions about what will improve their circumstances,” says Hassan.

The notion of handing cash to teenagers raises concerns, he acknowledges. “It makes … a lot of adults uncomfortable,” he says. “But if you are a young person growing up in New Orleans, it still remains a fact that you don’t have access to cash.”

Fifty dollars a week could buy gas to get to a job, contribute $200 a month to a family’s bottom line or make college preparation more realistic, he adds. And if the Rooted-4.0 micro-pilot goes the way larger-scale ones have, the psychological security provided by knowing the money will be there will lessen participants’ anxiety and enable them to plan for the future.

Some students might squander their cash transfers, Hassan concedes. But better they learn money management skills in high school than in college, where hard experience has shown leaders of high-performing high schools that small missteps by students often make it hard for them to persist and earn a degree.

Both Hassan and Johnson have personal experience with the way poverty creates instability for economically disadvantaged students. Hassan was born in Sudan, where his educational prospects were dim. When his mother won the U.S. diversity immigrant visa lottery, Hassan was the only one of her four children who was the right age to accompany her.

“I still feel like I shouldn’t be here, just by the odds,” he says. “I feel a sense of responsibility.”

See original article here: https://www.the74million.org/article/could-50-a-week-empower-high-school-students-to-set-and-meet-education-goals-this-new-orleans-school-aims-to-find-out/