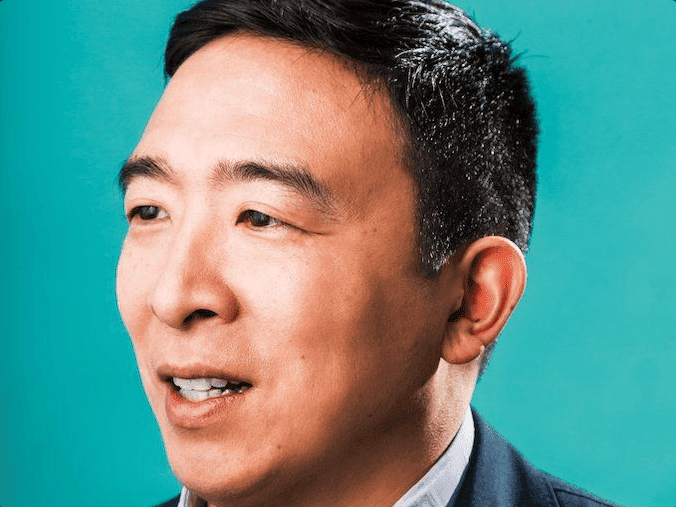

• Elon Musk has endorsed serial entrepreneur Andrew Yang’s run for Democratic presidential candidate, mostly based on the latter’s supper of universal basic income (UBI).

• UBI is at the center of Yang’s platform. It promises a set of guaranteed payments of $1,000 per month, or $12,000 per year, to all US citizens over the age of 18.

• The ideas behind UBI are centuries old, but they’ve been gaining traction within the Democratic field thanks to the support of candidates like Yang.

Over the weekend, Elon Musk shared his support for a Democratic presidential candidate – the serial entrepreneur Andrew Yang – and a radical social policy initiative, universal basic income (or UBI).

In a series of brief tweets, Musk said that he supported Yang, who previously founded Venture for America, and that UBI is “obviously needed.”

UBI is at the center of Yang’s platform, and, indeed, the motivating force behind it. As his campaign website declares:

Andrew Yang is running for President as Democrat in 2020 to implement the Freedom Dividend.

This form of UBI that he is proposing for the United States is a set of guaranteed payments of $1,000 per month, or $12,000 per year, to all U.S. citizens over the age of 18. Yes, that means you and everyone you know would get another $1,000/month every month from the U.S. government, no questions asked.

It’s fair to say that Yang’s candidacy provides the most public advocacy for UBI in America to date. Under his plan, every adult gets the 12 grand a year, regardless the cost of living associated with where they are in the country. It would stack with Social Security. He promises that it would be paid for through “consolidating” select welfare programs and implementing a value added tax, or VAT, which is part of why the rich, as well as the poor, would receive the monthly funding.

Yang’s idea has a long history – and promising recent results.

An old idea gets newfound interest

UBI is gaining newfound interest, but the system itself stretches back to the 16th century, when Spanish-born humanist Juan Luis Vives praised a system of unconditional welfare. “Even those who have dissipated their fortunes in dissolute living – through gaming, harlots, excessive luxury, gluttony and gambling – should be given food, for no one should die of hunger,” Vives wrote in 1526.

Over the next few centuries, political scientists and sociologists honed the idea of a minimum income even further. In 1797, the American revolutionary Thomas Paine advocated for a “national fund” in the pamphlet “Agrarian Justice,” for which every American would be awarded fifteen pounds sterling when they turned 21, with another ten pounds per year after age 50.

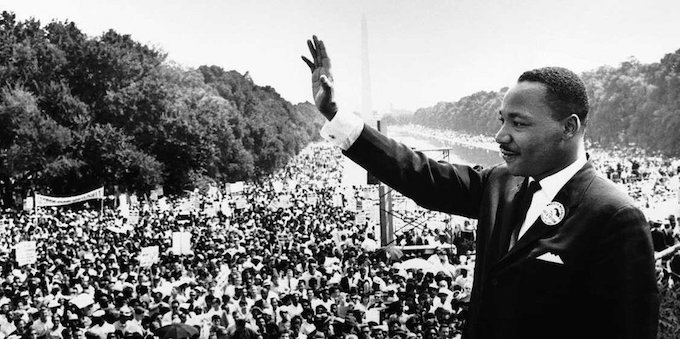

Even Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. declared his support for basic income at a Stanford lecture in 1967.

“It seems to me the Civil Rights Movement must now begin to organize for the guaranteed annual income and mobilize forces,” King said, “so we can bring to the attention of our nation this need … which I believe will go a long, long way toward dealing with the Negroes’ economic problem and the economic problem many other poor people confront in our nation.”

In his final book, Where Do We Go From Here: Chaos or Community?, King observed that “no matter how dynamically the economy develops and expands it does not eliminate all poverty.” Hence the need for the nation to create full employment – or create incomes.

A big experiment, briefly lost to history

The decade between 1969 and 1979 marked a crucial turning point in the basic income movement for two reasons.

The first was President Richard Nixon’s 1969 proposal of the “Family Assistance Plan.” The legislation promised to give an additional $10,400 (in 2016 dollars) each year to families who had kids, depending on income. While the FAP easily made it through the House of Representatives, it ultimately died in the Senate.

The second was the “Mincome Program” that took place in Manitoba, Canada. Between 1974 and 1979, residents in the city of Winnipeg and smaller nearby town of Dauphin received additional monthly income, again based on their income levels.

It wasn’t until University of Manitoba economist Evelyn Forget discovered the Mincome files 20 years later that anyone realized what a success the program had been.

Forget’s research showed hospitalization rates fell by 8.5%, high school completion rates went up, and new mothers could afford to work less. And in general, few people stopped working – one of the key fears that’s often cited about basic income.

By nearly all measures, the conclusion was clear: Basic income held serious potential as a way to lift people out of poverty.

A radical idea tiptoes toward the mainstream

Forget’s research was critical because it helped revive the basic income movement after two decades of dormancy. Advocates had been praising the concept all the while, but only within the last decade have mainstream economists considered putting it back into action.

Some of the biggest names in business, particularly the tech world, have endorsed UBI, including Musk, Mark Zuckerberg, and Richard Branson.

In over a dozen countries and many more cities around the world, academics and policymakers have launched basic income experiments of their own – some completed, some ongoing. Many of the projects have already replicated the effects Forget found in the late 1970s. Much of the contemporary research on UBI and related programs has been carried out in the developing world; the World Bank largely found that the global poor spend the money on household goods, health care, and that various costs that come with schooling.

As has been observed elsewhere, the biggest issue with basic income is that it still needs more large-scale, years-long empirical study in developed countries to figure out where or not it “works.” Given that UBI remains something of a political Rorschach test – the term “government handout” remains a lightning rod in 2019 – it needs more to be more tested than debated. With the right studies ran, the policy could be based on evidence, rather than argument.

That’s why Yang’s campaign, and the Freedom Dividend its wrapped around, doesn’t fail if the technologist doesn’t end up in the White House. As UBI becomes more mainstream, it stands a stronger chance of being better researched – and ending up as viable policy.