By F. Amanda Tugade and Virginia Barreda

See original post here.

Until last July, Kelli Wright was living with her four sons in a snug two-bedroom apartment on Des Moines’ north side.

The single mother says she dreamed of moving her children into a bigger home and in a safer neighborhood. But she couldn’t afford to on her salary alone.

She says she could only do so with the help of a guaranteed income program that paved the way for financial stability. Through Uplift – The Central Iowa Basic Income Pilot, Wright was one of 110 people who has since last May received $500 a month to help pay for basic needs like food, rent, utilities and child care.

“To some people, that doesn’t seem like a lot. But when you are struggling paycheck to paycheck to pay your bills, that $500 actually goes a long way,” she told the Des Moines Register after speaking about the program on a panel Wednesday night at the Windsor Heights Community Center. “You’re actually able to pay off some of the debt you’re in and then get caught back up.”

Wright said the extra cash gave her room to save money and time to find a place more suitable for her family.

The guaranteed cash assistance program is meant to test if an unrestricted, no-strings-attached monthly check is an effective way to reduce poverty, according to Ashley Ezzio, senior project coordinator at The Tom and Ruth Harkin Institute for Public Policy & Citizen Engagement, which is coordinating the study.

The year-one update also comes on the heels of a new law the Iowa Legislature passed in May that bans local governments from adopting guaranteed income programs, leaving cash assistance pilots like UpLift on shaky ground.

Program coordinators said UpLift, initially financed with $2.5 million from 11 public and private sources, will continue as planned through 2025 with donations.

One year into the two-year study, here’s what we know:

How have participants used their $500 monthly income?

Ezzio and Michael Berger, another program coordinator, said many participants have used the funding for the essentials, including housing and food costs, to create safer spaces and bring stability to their families.

Food and groceries have made up the largest portion — just under 42% — of participants’ spending over the past year. Retail follows at 26%, which includes places like Target and Walmart, Ezzio said.

More:New basic income program gives central Iowans $500 a month — no strings attached

But Ezzio said many also have taken “healthy risks,” including entrepreneurial ventures and investments in education.

Skye Onyx and Nicole Wilson, who joined Wright and two others Wednesday, said they used the money to cover their expenses while searching for stable work with better pay and planning out their next steps. They credit the funding to giving them the financial wiggle room to rethink their careers and figure out how to best invest in their futures.

Onyx went on to earn a certificate in sterile processing, helping her land a full-time job. Wilson used the money to expand her nonprofit, Let’s Convo, which aims to reduce social isolation for older adults through conversation. Wilson said she also used the money to help kick start her husband’s lead abatement businesses.

Before UpLift, Wilson was laid off from two jobs and struggling to pay insurance — a situation, she said, many others face. She said she and her husband have used assistance programs such as food stamps, Medicaid and Section 8 vouchers but have found the UpLift program is unique.

Because the guaranteed monthly income comes without strings, Wilson said she had the freedom to “nourish” her nonprofit and solidify its services.

“When there’s a program like this, there are people like us who will benefit from it. It’s that ripple effect,” she explained. “It’s going to benefit not just us. It’s going to benefit our children. It’s going to benefit the community as a whole.”

Who are the participants?

- Of the 110 participants, a majority — 81% — are Polk County residents, according to a news release from the Harkin Institute. Ten percent live in Dallas County, and 9% are from Warren County. Program leaders sought to focus on those three counties to see how the monthly checks would affect people in need living in rural, micropolitan and metropolitan areas.

- The Harkin Institute also provided a breakdown of the participants’ racial demographics: 55% of them are white. Twenty-six percent identified as Black or African American, while 10% said they are multi-racial or another race. Roughly 5% shared they are Asian, and another 5% said they are Latino.

- Participants also reported they are working and earning an average household income of just above $24,000 a year. Many participants said they are working full time and spend roughly 44% of their income on rent or other housing costs, about 14% above the national standard.

- Participants’ average age is 37 and 85% are female. The majority — 63% — of participants said they were single, while 26% are married, and another 11% are in a relationship, the Harkin Institute reported. The average number of people in the household is four, with two children per household.

How is the Harkin Institute tracking participants’ spending?

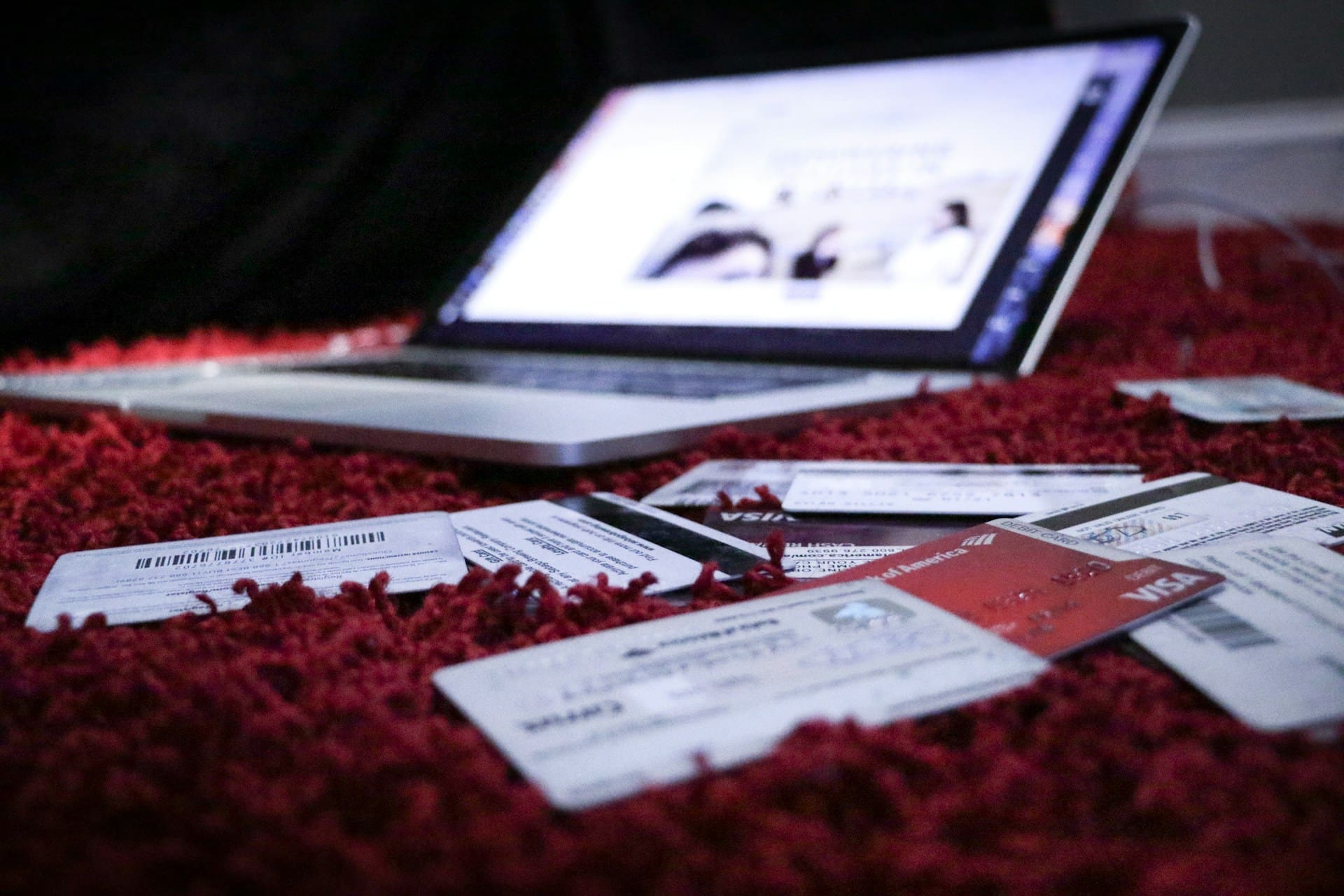

While researchers aren’t tracking participants’ specific purchases when they swipe the prepaid debit card, they are tracking categories, such as food, retail, education or transportation, Ezzio said.

Participating families also are being asked to take periodic surveys throughout the study that will allow researchers from the University of Pennsylvania’s Center for Guaranteed Income Research and Des Moines University to determine if the money has an impact on their physical, mental, emotional and financial well-being, Berger said. Surveys come in every six months for 30 months.

About 80% participated in the first survey, Berger said. The Harkin Institute is in the midst of its second round.

Data from the surveys, as well as qualitative interviews with participants, are going to give insight into how the money is used. The findings will be available publicly after the two-year pilot ends. But what happens with that data will be left up to the community, Ezzio said.

How has legislation affected UpLift program?

In early May, Gov. Kim Reynolds signed into law Republican-led House File 2319, which prohibits cities and counties from participating or enforcing programs that make “payments to individuals under a guaranteed income program.” The bill was spurred in part by UpLift.

Republicans who backed the law’s passage criticized guaranteed income programs as the wrong direction to take while addressing poverty and expressed concern that they could become more widespread. Rep. Steve Holt, R-Denison, called the programs “socialism on steroids.”

Ezzio said she was disappointed to hear of the bill’s passage but said the program is set to continue under private funding, with final findings set to be published in 2026. She said the bill’s passage doesn’t reduce the importance and value of the data and stories being collected throughout the study. The concept behind UpLift is meant to help find best practices to address poverty, she said.

“I think that the point of starting UpLift was to really do a pilot and say, ‘Is this one solution? Can we glean some insights into how to best effectively mitigate the effects of poverty in our community?'” Ezzio said.

Ezzio said the 6,000 applications the Harkin Institute received from eligible participants at the start of the program is an indication of the need for innovative ideas to tackle the root causes of poverty. The applicants were not just people living under the poverty line but the working poor who still are not able to meet their basic needs, she said.

“We know that 110 (people) is just a drop in the bucket but we’re really hoping that with the research that comes with this, it informs future decisions around how we can really be helping our community,” Berger said.