By Peter Gray

See original post here.

Work is a word with several different but overlapping meanings. Here I’m using it as a synonym for paid employment.

Work, by this definition, dominates our lives. We live in a world of work. It is how we survive. It is how, on most days, we spend half or more of our waking hours (not counting the commute).

It is a source of constant concern. We fret about too much work, or sometimes we brag about too much work, and we worry about too little of it. Work is how most of us define ourselves. “I’m a journalist… or a plumber… or a lawyer.” Why does work dominate our lives and dictate our identity?

In a previous post, I noted that in 1930, the economist John Maynard Keynes (1930/1963) predicted that, by the end of the 20th century, because of automation, the average workweek would be about 15 hours. That, he predicted, would be sufficient to produce everything we need for a comfortable life. In one sense he was right: Automation has greatly reduced the amount of human work, whether physical or mental, required to produce everything we reasonably need. But he was wrong in his prediction that we would work less. The average work week for most today is little different than it was a hundred years ago. Why?

One answer to this question, which I described in the previous post, has to do with the economy. We live in a world where less work is needed, but we have not adapted our economic system in a way that permits less work for most people. We still have a system of work for wages as the means of distributing what people need, and we still have wages set at a level that, for many people, necessitates many hours of work to support themselves and their family. The powers at the top of our economic hierarchy (the so-called “job creators”) have no interest in increasing wages (for anyone other than themselves), so most people still need to work about 40 hours a week to support themselves and their family.

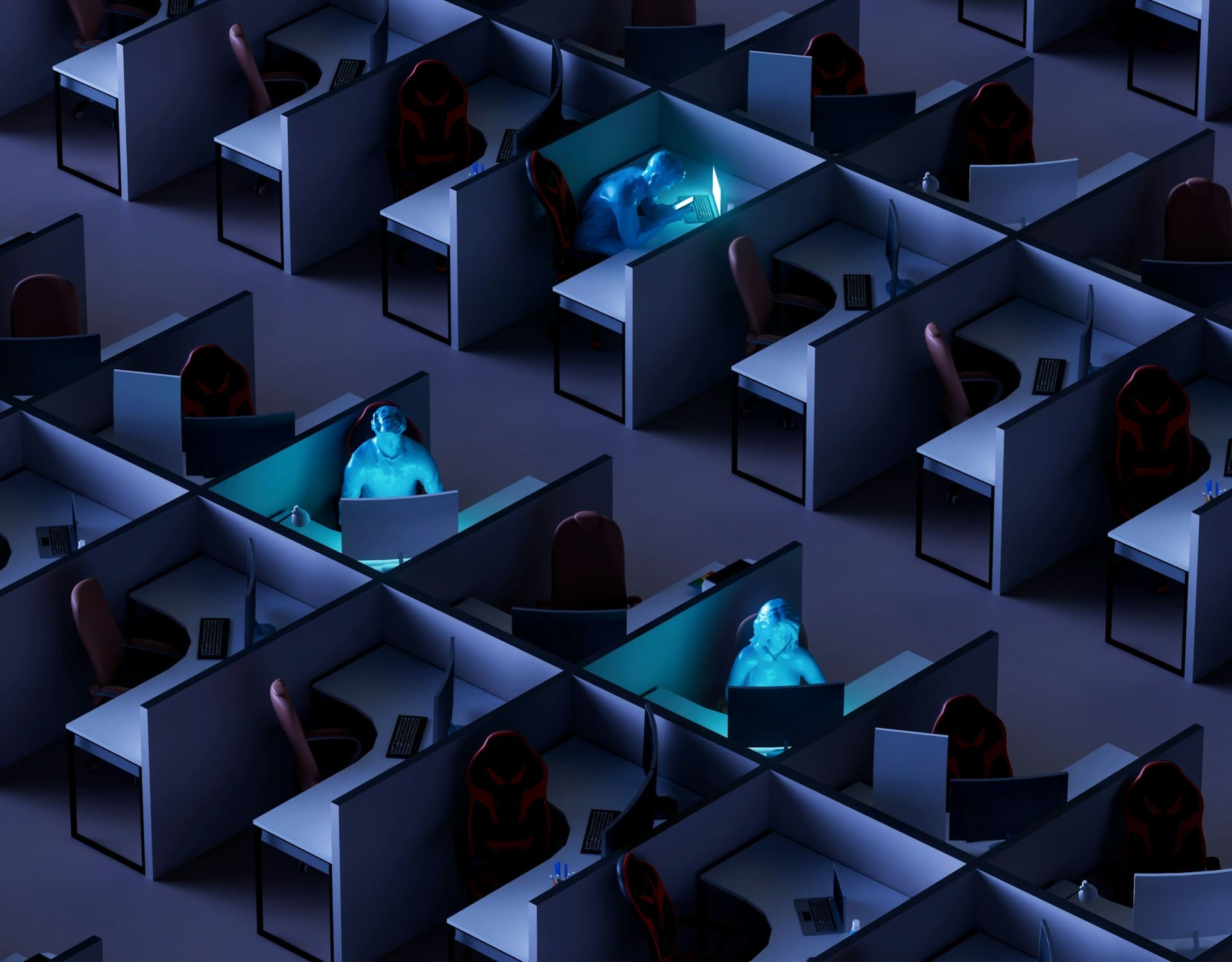

Instead of reducing work, our approach has been to continuously create new jobs Some of these jobs are useful, with social value, but many are not. In fact, as anthropologist David Graeber has argued in his book Bullshit Jobs (2018), many add no social value or are even harmful to society and the environment (see my previous post for examples).

We could, if we had the political will, reduce through legislation the hours people must work, thereby improving lives and, at the same time, benefiting the environment. We could increase the minimum wage and decrease the workweek gradually, over time, in steps that would not dramatically disrupt the economy, eventuating in something close to the 15-hour week predicted by Keynes.

Or we could, as some have proposed, provide a universal basic income, paid for by increased taxes on the very rich. Again, this could be instituted on a gradual basis. The powers that be—the ones who profit most from things as they are—provide roadblocks to such changes. But I think there are other reasons, too, why the rest of us have not demanded those changes.

We Are Products of a Culturally Ingrained Work Ethic.

We are raised to believe in the moral virtue of work. Historians attribute this in part to the Protestant Reformation, going back to the 16th century, whose leaders viewed work as God’s will and play as the breeding ground of sin, and even more to the Industrial Revolution of the 18th and 19th centuries, when the economy changed from primarily agricultural to factory-based industrial. The schools that arose in the Protestant era and became compulsory and state-supported in the 19th century and continue essentially unchanged today (but even more consuming of children’s time) were designed explicitly to promote the ideology of work and suppress the natural human desire to play (more on the history of schooling here).

Our continued implicit beliefs that work is good for us derive not just from our cultural history and our schooling (where learning is turned into work), but also from the continued propaganda deriving ultimately from those who profit most from the work of others. We are made to feel ashamed if we take what is called a “handout,” even if we are disabled or burdened with the unpaid labor that comes from caring for others who need our care.

Our culturally ingrained work ethic may also lead us to humblebrag about being overworked. We may “complain” to friends and relatives about being too busy with work and not having time to do the things we would really like to do, but research by Silvia Bellezza and colleagues (2016) suggests that this may often be more boast than complaint. In a series of studies, these researchers found that people—at least in the Unites States (it didn’t hold up in Italy)—accord higher status to those who work more, other things being equal, than to those who have more leisure time. The assumption is that long hours of work imply that the person has desirable qualities that make them much valued by employers. This is only true, however, for people who work more by choice, not for those who work more out of necessity.

And so, as a society, we don’t push as hard as we might for reduction in work. Instead, we push for more jobs.

Too Many Have Forgotten How to Play Outside of Work.

In a research study conducted in the late 1980s, Mihaly Csikszentmihalyi and Judith LeFevre (1989) found that many workers were happier at work than during free time at home. Their reports on what they were doing at work and home help us make sense of this seemingly paradoxical finding. At work they were often engaged, in a social setting, in challenging, skill-stretching tasks that were within the range of their competence and over which they had a good deal of control. These are the conditions that lead a person to experience work as play, or at least as highly play-like. At home, in contrast, they tended to engage in passive activities, such as watching television or lying on the couch trying to sleep, with relatively little social engagement.

The primary message I take from this study is that many adults in our work-obsessed society had, by the 1980s, forgotten how to play. At work, at least in some kinds of jobs, they found themselves in a situation that had play-like qualities. During leisure time away from work, they became, by comparison, both mentally and physically passive. They saw themselves as relaxing, recovering from work, but in fact were depriving themselves of the joy they might gain from more engaging activities.

I don’t think this was just because they were exhausted at work and needed to rest at home. In earlier decades, when work was, if anything, more exhausting than in the 1980s, adults often engaged in active, play-like activities during their free time. At least this is my impression, though I don’t know of any quantitative research showing it to be true. I recall, in the 1950s when I was a child, my parents and other adults engaged in softball games on summer evenings and weekends, socializing with friends over cards, skill-demanding hobbies of various sorts, gardening, and chores such as lawn maintenance and home repairs that people tend to hire out today. Such activities seemed to be a great source of satisfaction and perhaps more effective in rebounding from work than hours on the couch.

Are We on the Cusp of Change Toward a “Post-Work Society”?

The world keeps changing, and we are now experiencing a revival of calls for less work. Some are proposing change toward what they call a “post-work society” (Minerva, 2023; Rattee, 2023). Nobody suggests we can do away with work entirely, but many believe that Keynes’s idea of a 15-hour workweek is well within reach. Another idea in this movement is that we could change the nature of work, so it is more varied and everyone could choose a balance of physical and mental work rather than just one type of work, which would improve health and make work less tedious.

The post-work movement has been brought on by several social forces. The work shutdown during COVID led some to see advantages—for workers, employers, and the environment—of a world in which people aren’t traveling back and forth to work five days a week. Digital technology has made it possible for more people to work from home, which means they can live wherever they want, including near friends and relatives and at places where they like to play, and can choose their own hours of work.

More people are choosing to work less, even though it means less income, so they have time for other activities that are meaningful to them (for many examples, see Balderson et al., 2021). Dramatic advances in artificial intelligence have led to predictions of a raft of jobs becoming obsolete and revival of concern that there won’t be enough work for everyone if we insist on maintaining 40-hour workweeks.

It will be exciting to see what the next few years will bring.

Final Thought

Play apparently does not come naturally to us adults today. Ironically, for many it seems to occur more when at work than during free time at home. Perhaps, if we want more play in today’s world, we must plan for it, arrange for it—dare I say, even discipline ourselves to come home to something other than the couch. Once we get started on some hobby we used to enjoy, or join a social group, or create a vegetable garden, we won’t regret it. We will start having more fun away from work than at work.

As always, I welcome your thoughts and questions. Psychology Today does not allow comments, so I have posted this on a different platform where you can comment and read others’ comments here.

References

Balderson, U., et al. (2021). An exploration of the multiple motivations for spending less time at work. Time & Society, 30(1), 55–77.

Bellezza, S., Paharia, N., & Keinan, A. (2016). Conspicuous consumption of time: when busyness and lack of leisure time become a status symbol. Journal of Consumer Research, 44, 118-138.

Csikszentmihalyi, M., & LeFevre, J. (1989). Optimal Experience in Work and Leisure. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 56, 815-822.

Graeber, D. (2018). “On the phenomenon of bullshit jobs: a work rant”. Strike Magazine. August 7.

Graeber, D. (2018). Bullshit jobs A theory. Simon & Schuster.

Keynes, J. M. (1930/1963). Economic possibilities for our grandchildren. Reprinted in John Maynard Keynes, essays in persuasion. New York: Norton.

Minevich, M. (2023). Charting the roadmap to a post-work society. Forbes, July 27.

Rattee, A. (2023). A new model of work in a post-work society. Medium. June 18.