Joe Manchin dealt the final blow to the Child Tax Credit. But the reasons it lapsed are deeper than one man.

By: Dylan Matthews.

See original post here.

I wrote a long piece last week about how and why I failed to predict just how bad inflation would get. That got me thinking about some other current developments that caught me by surprise. The biggest among them: the death of the expanded child tax credit put in place by the Biden administration as part of the American Rescue Plan.

Before Biden came into office, the credit maxed out at $2,000 per child ($1,400 for kids in families too poor to owe income tax), was bundled with tax refunds, and specifically left out families with little or no earnings. About one-third of children were excluded from the full credit, including over half of Black and Hispanic children, as well as 70 percent of kids raised by single moms. That’s precisely the population in most need of financial help.

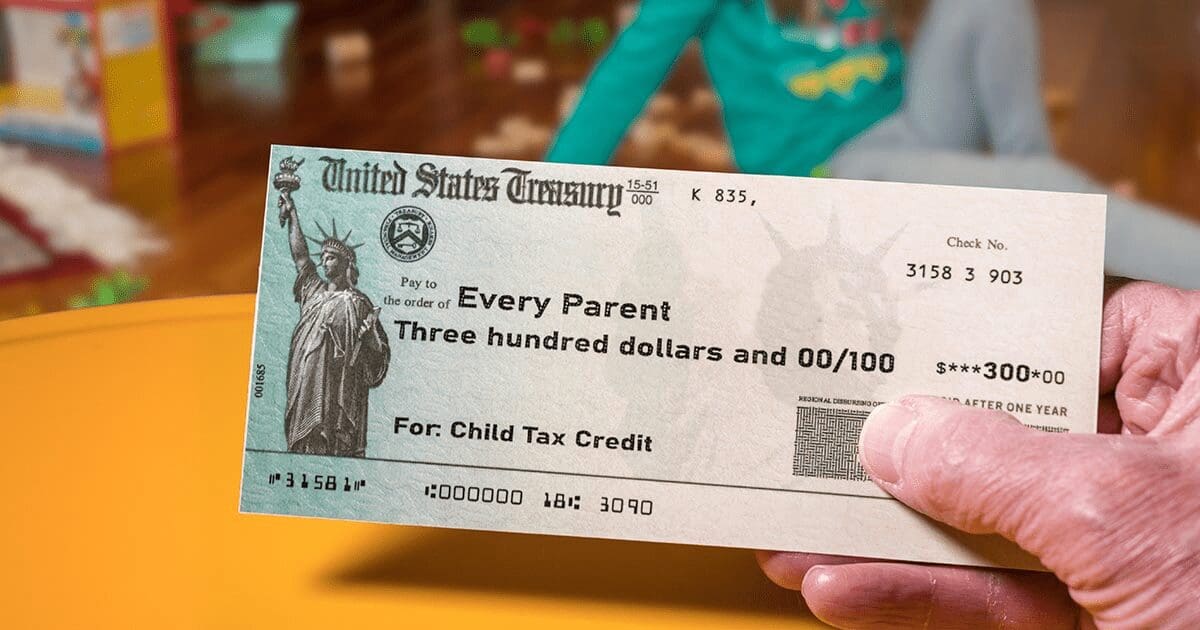

The Biden changes dramatically increased the credit to $3,000 per kid aged 6 and over, and $3,600 per kid under 6; paid it out monthly; and made the full credit available to all poor children, eliminating the previous “phase-in” rule that capped the credit at 15 percent of a family’s income.

The Columbia Center on Poverty and Social Policy estimated that in July 2021, when the first monthly checks went out, the US child poverty rate dropped to 11.9 percent, from 15.8 percent the month before. It was the lowest rate on record since reliable data started in the 1960s, and likely the lowest rate in American history. Some polling data suggested that the share of households reporting problems with hunger dropped substantially after the credit went out.

Giving families money, it turns out, is a simple way to reduce poverty, and given that child poverty imposes hundreds of billions of dollars of social costs a year, I thought it was a very worthwhile investment. But the expanded credit expired at the end of December. The Columbia team estimates that 3.4 million more children were in poverty in February 2022 than in December, a slide into need due almost entirely to the loss of the credit.

So why did Congress let one of the most important child poverty policies ever enacted lapse?

The Joe Manchin failure, and the larger failure

There’s a very simple answer to why the child credit didn’t continue: there weren’t 50 senators willing to support its extension. And most public reporting suggests the main holdout was Sen. Joe Manchin.

Axios’s Hans Nichols, the DC press corps’ premier Manchin-whisperer, reported last October that the West Virginia Democrat was demanding that the credit include a “firm work requirement” and not go to families making over $60,000 a year.

That’s a huge departure from the Biden CTC, whose major attraction was that it didn’t phase in with income and went to all poor households. The credit also went to many families with six-figure earnings, and changing that as Manchin desired would force a de facto tax increase on upper-income folks.

Some reports have also suggested that Manchin thought the money would go to buy drugs — an evergreen concern about cash programs for the poor (Manchin’s office declined to confirm or rebut that he expressed this concern privately). This suspicion is ill-founded; the best evidence review on the question I know of concluded there’s little reason to believe cash transfers increase drug or alcohol abuse.

Manchin’s fear that the credit would disincentivize work is more credible, and the subject of some scholarly disagreement. The old child credit “phased in” with income, with beneficiaries getting 15 cents for each extra dollar in earnings. That in theory encouraged people to work, and University of Chicago economists Kevin Corinth and Bruce Meyer argued that getting rid of the phase-in would lead many people to drop out of the labor force. Other economists disagreed. But even if you think the credit mildly disincentivizes work, it still substantially reduces poverty. I’d argue that even if Corinth and Meyer are right, the policy was still worthwhile.

So why does Manchin oppose it anyway? I suspect it has a lot to do with being a Democratic senator from a state that Donald Trump won in 2016 and 2020 by about 40 points. Manchin barely hung onto his seat in 2018 during a heavily Democratic year, and it’s understandable he doesn’t want to go too far out on a limb for a big government spending program. Millions of West Virginians benefited from the policy, but it’s ultimately a very conservative state skeptical of liberal policy initiatives. (Not to mention voting against your immediate economic interests is pretty common — plenty of wealthy people in blue states like California and Connecticut vote for candidates who’ll raise their taxes.)

The structural challenge

At some point, though, focusing too much on one man can mislead more than it informs.

The bigger questions, I think, are a) why beneficiaries weren’t able to fight to keep the benefit, like the beneficiaries of Obamacare successfully did in 2017, and b) whether doing this kind of legislation on straight party lines is viable.

The 2017 rescue of Obamacare was a great illustration of a classic political science theory from Berkeley’s Paul Pierson. Pierson noted that even conservative leaders like Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan hadn’t been able (or even really attempted) to roll back foundational welfare state programs like the National Health Service and Social Security. He argued that beneficiaries became invested in these programs and would revolt against any politicians who threatened them.

That’s basically what happened in 2017: Republicans should have had the votes to repeal Obamacare after Trump took the White House, but the prospect of throwing millions of people off Medicaid started to look so politically poisonous that several GOP senators bolted and killed the effort.

I thought this would happen in 2021: letting the child tax credit expire would so enrage parents benefiting that Congress would be forced to extend it.

That wasn’t so.

Maybe the three rounds of stimulus checks primed voters to think of the child credit payments as temporary, that, like pandemic aid, the money would naturally come to an end. Maybe the people for whom the credit mattered most were too poor to have the time or resources to organize. Maybe the pandemic inhibited organization. Maybe it’s a matter of status quo bias: the credit was set to expire, and it’s always easier for Congress to do nothing than to pass new legislation to extend a program.

Whatever the reason, beneficiaries couldn’t and didn’t save the credit. And this kind of policy reinforcement is the main reason Democrats have been able to expand the welfare state on party lines in the past (see, again, Obamacare, or Bill Clinton’s earned income tax credit expansion in 1993). Normally, Republicans could just repeal policies like this when they next take power, just as they reversed Obama’s upper-income tax hikes of 2012; but because the policies create their own constituencies, Republicans can’t actually do that.

But if that kind of constituency doesn’t develop, it means policies like this are inherently vulnerable and can be cut off the next time there’s a change in party control.

That suggests to me that the only path forward is some kind of bipartisan deal on the child tax credit.

The Niskanen Center’s Samuel Hammond and Robert Orr have a great piece on what this would look like. It’d probably entail keeping an income phase-in and excluding households with absolutely no earnings. Hammond and Orr suggest keeping a very-young-child credit that’s fully available to people with no earnings, but concede that even this might have to fall by the wayside to earn Republican votes.

That’s tragic, to me, because it excludes people who profoundly need help. But it might be the only way to make a policy like this work in America.