The fundamental building block of a strong social contract is citizens being able to trust their Governments. UBI is becoming part of the new social contract.

By: Dr Stephen Kidd

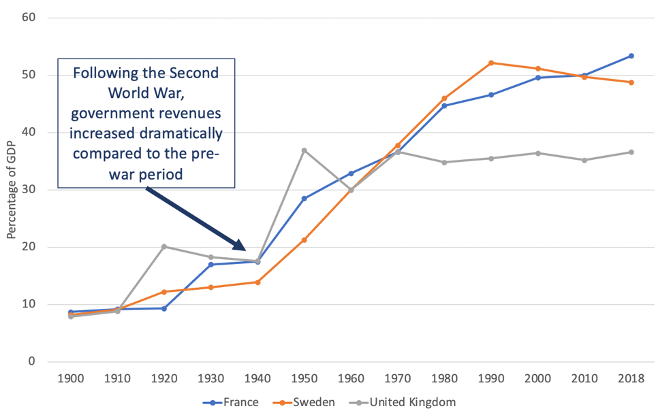

A strong social contract is a precious resource in any country. Without it, citizens will be reluctant to pay their taxes resulting in governments being unable to collect the revenues they need to offer good quality public services to their citizens. Indeed, one of the main challenges facing countries across the Global South is low government revenues: in most, revenues are less than 20 per cent of GDP, similar to those of Europe prior to the Second World War when poverty, inequality and the Great Depression reigned, and fascism was able to flourish.

The fundamental building block of a strong social contract is citizens being able to trust their Governments.

As Sweden’s Ministry of Finance argues, governments build trust through the provision of universal public services.

The introduction of universal public services – including universal social security – following the Second World War transformed Western Europe. Whereas, prior to the war, social assistance for the poor dominated social policy, the Second World War marked a paradigm shift in European social policy. Progressive politicians were elected who, as a priority, established universal public services, including schemes such as universal old-age pensions and child benefits. In a relatively short period of time, they built trust among their citizens, enabling governments to vastly increase levels of taxation. As Figure 1 shows, in some of the most successful countries government revenues increased to over 50 per cent of GDP. Western Europe was transformed: social cohesion was strengthened, inequality was tackled, peace was maintained, economies grew, and prosperity was shared among the many, not the few.

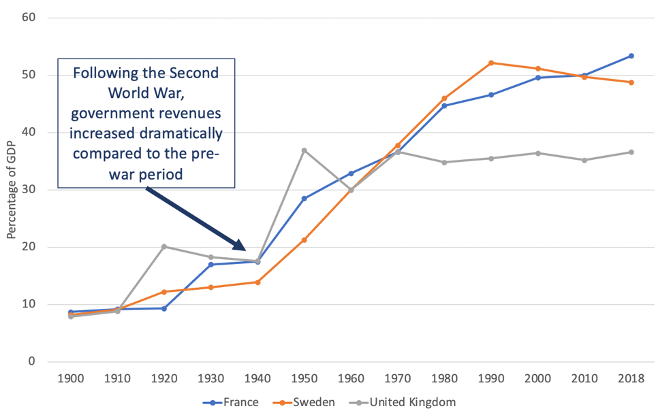

Following the Second World War, therefore, many countries in Europe were able to recover from the shock of the conflict by creating a virtuous that delivered decent societies by building greater trust in government. As illustrated by Figure 2, by receiving good quality universal public services, the trust of European citizens in their governments grew, which strengthened the social contract.

As a result, citizens became more willing to pay taxes which generated higher government revenues which, in turn, enabled governments to invest in even more high-quality public services.

As a result, the virtuous circle continued and, to a large extent, conflict in Europe disappeared while societies became more peaceful, cohesive, equal and prosperous.

How trust is undermined in the Global South through poverty-targeted social security

An underlying cause of low tax revenues across the Global South is the limited trust that citizens have in their governments. This is due, in part, to the low quality of public services which undermine social contracts and discourage people from paying taxes. In fact, in many countries, the middle class and rich have abandoned state-financed health and education services and opted for private provision. This, naturally, deepens their reluctance to pay the taxes that would fund the public services that they no longer use.

The model of social security that is prevalent across today’s Global South has a strong emphasis on programmes targeted at the poorest members of society, following the model not only of pre-War Europe, but of 19th Century Europe. This model contributes heavily to the undermining of trust in government. As a result of targeting the poorest members of society, the majority of the population – the so-called ‘missing middle’ – are, by design, excluded from the national social security system while the ‘poor relief’ programmes that are delivered tend to be of poor quality: targeting errors are high while selection is widely perceived by citizens as arbitrary and unfair; transfer values are low, with their real value falling year on year; conditions and sanctions are often used, which undermine dignity and self-respect; recipients are often stigmatised; and, local elites often use programmes as a means of exercising power and control over recipients. Indeed, the proxy means test – a targeting mechanism that is particularly arbitrary in its selection of recipients – functions as if it were designed with the sole purpose of undermining trust in government. Yet, it continues to be strongly promoted across the Global South, often in the guise of social registries.

A strategy to rebuild trust in government across the Global South through universal social security.

Building trust and a strong social contract is particularly important in fragile states. Unfortunately, normal practice is for donors and governments to implement poor quality, poverty-targeted social security schemes that contribute to undermining trust among the citizens of fragile states: in effect, they are in danger of fanning the flames of an already dangerous fire. Universal social security is the answer to fragility.

Just as the fragile states of Western Europe were healed after the Second World War through universal public services – including social security – the same solution must be applied to today’s fragile states across the Global South.

The answer is not “there is no fiscal space:” instead, finding the fiscal space, which is almost always available for universal social security – such as an old-age pension or child benefit – if there is political commitment, is the only answer. It worked in Europe and, arguably, it has been successful in other previously fragile states, including Georgia, Kosovo, Nepal, South Africa and Timor-Leste. A national old-age pension and/or child benefit in countries such as Afghanistan, Iraq, Myanmar, Somalia, South Sudan and Yemen could be a game-changer in building national social contracts and in signalling to everyone that they are part of the nation-state.

Conclusion

In conclusion, trust in government is the basic building block of any successful nation-state. It needs to be at the very top of the list of government priorities since, once trust is undermined, the state itself can be threatened. History tells us that a key factor in building trust is the provision of universal public services, since they can be enjoyed by everyone on an equal and impartial basis. And, if trust is to be built quickly, the best means of doing so is through universal social security.

COVID-19 has created a major crisis across all countries and has highlighted the failings of the prevailing social and economic policies in most countries in the Global South. A key question is whether COVID-19 can be the catalyst for the type of paradigm shift in social and economic policy that occurred across Western Europe following the Second World War. If this change in paradigm is to happen, it will need progressive politicians and development partners to come together and move away from the poor relief model that has dominated policy thinking across the Global South. Instead, they need to have an unremitting focus on building the type of universal social security system that transformed the social contract in Europe. Listening to Sweden’s Ministry of Finance could be a good first step.