Estimates are that Congress needs to spend 4 times more than it is currently proposing, according to one estimate. Can we afford NOT to do it?

By Emily Stewartemily | stewart@vox.com

What it would really take to save the economy? About four times what Congress is currently proposing, according to one estimate.

The clock is ticking on much-needed stimulus for the economy amid the Covid-19 pandemic. Not only is it too late to stop some of the damage, but chances are, any stimulus that does come is going to be much, much too little to be effective.

The latest bipartisan offer on the table in Congress is a $908 billion stimulus bill. It’s a substantial number that’s about $500 billion more than Republicans recently proposed. But according to a new paper from economists Adam Hersh and Mark Paul commissioned by the Groundwork Collaborative — a progressive economic think tank — really reviving the United States economy could require three, even four times that: The pair estimates Congress would need to pass $3 to $4.5 trillion in economic relief in the near term to get the economy to reach its full potential.

“Economics has given us all the tools we need to address the crisis, and we just need the policymakers to open up the checkbooks of the US government,” said Paul, a political economist at the New College of Florida and a Roosevelt Institute fellow.

While the Federal Reserve has taken extraordinary measures, such as slashing interest rates and resuming securities purchases, to boost the markets and economy using the tools it has available, Congress has not followed suit. And that’s likely to cause long-term damage as well as a slower recovery, with the people at the bottom of the economic ladder left behind. Hersh and Paul make the case that the best way to avoid this scenario is for lawmakers to inject trillions of dollars into the economy to achieve full employment — and create a new normal that is better for all Americans.

The researchers also say it’s important to enact automatic triggers that will renew key parts of a stimulus package as long as necessary. The extra $600 a week in expanded unemployment insurance ended in July, and other stimulus programs are set to expire at the end of the year. But that isn’t because the economy is running on all cylinders and the pandemic is over. It’s because Congress put in place arbitrary — and overly optimistic — timelines on when support would no longer be necessary.

What the economy really needs: A lot of money to a lot of people, now

The United States economy added 245,000 jobs in November. Pre-pandemic, that would have been a decent amount, but in the current moment, it’s woefully insufficient. The US is still 10 million jobs short of the employment level when the coronavirus hit, and if this pace of recovery holds, it will be years before those jobs are recovered.

The economy isn’t as bad as some people feared at the outset of the pandemic — the current unemployment rate is 6.7 percent — but it’s not great. What’s more, that 6.7 percent number masks the number of people who have given up on job searching and dropped out of the labor force altogether. Women, in particular, are leaving the workforce at an alarming rate. If the labor force participation rate matched the rate in 2007 before the Great Recession, Hersh and Paul estimate that the unemployment rate would be 13 percent — nearly double the official number.

“We know that right now and over the past several business cycles, a lot of people have been disappearing from the labor force who otherwise should be working,” Hersh said. “They’ve dropped out by the millions, so we’re dramatically undercounting what the real rate of unemployment is.”

Digging out of that hole would require trillions of dollars, though the exact amount depends on the multiplier — basically, how much bang the federal government could get for its buck.

One particularly effective way of increasing that multiplier would be to give cash assistance, like the $1,200 checks that went out to many Americans in the spring. Money that goes to those that need it most is generally a more successful stimulus arrangement, because those people tend to spend the money and put it back into the economy instead of saving it.

And millions of Americans are increasingly in need:

According to Census Bureau data, one-third of adults in the US are having trouble paying for usual household expenses.

“We know that [money] is just going to right back out the door when they get it,” said Hersh, the director of Washington Global Advisors and a research associate at the Political Economy Research Institute at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Analyses from the Congressional Budget Office find that each dollar of net spending given to corporations generates about $0.40 in extra economic activity and every dollar given to high-income people generates $0.60. But Hersh and Paul say that a dollar in direct transfer payments to an individual generates $2.10. The impact is higher when it goes to people who are financially stressed and have less disposable income, and when it goes into regional economies that are particularly impacted. People need money, and so do state and city government whose budgets were slammed by the pandemic.

One unknown regarding multipliers like direct transfers is the effect of social distancing — as long as the virus is still spreading, spending habits will be far from normal, and the economy can’t get back to normal.

But the main takeaway is that Congress should inject a lot of money — and do it fast — to repair the damage caused by two recessions arriving over the span of about a decade. One important lesson from the Great Recession is that fiscal stimulus efforts fell short, and in turn, the recovery was slow, as Hersh and Paul write:

Michigan did not return to its pre-Great Recession level of output until 2015. Arizona did not surpass its pre-recession level of output until 2016. Connecticut’s economy never recovered: by the time the pandemic began, Connecticut’s gross state product stood 4.2 percent below its 2007 level, after adjusting for inflation. As a nation, relative to pre-Great Recession trends, an estimated seven million potential workers have gone missing from the labor force in the face of poor job prospects resulting from insufficient macroeconomic policy support.

The US risks making the same mistake now, particularly if Congress doesn’t spend enough money to really boost the economy and get the unemployment rate so low that workers are pulled back into the market. Doing so would help workers of color, especially Black workers, who historically have a much higher unemployment rate than white workers.

“In order to bring all those people back into the labor force and see wage gains extend to those groups, we need to get unemployment down to a very low level,” Hersh said.

Some critics will point to the federal deficit and say such an expenditure would add too much to the country’s debt and endanger the US economy long term.

Republicans in Congress have already begun making this argument, claiming that Democrats’ plans for a multi-trillion-dollar stimulus go too far. But Republicans also passed a tax cut bill that disproportionately benefited corporations and the wealthy in 2017 without worrying very much about the estimated $1.5 trillion it is projected to add to the debt.

The Federal Reserve has said it plans to keep interest rates low for a long time, meaning borrowing costs will remain low. If there were ever a moment to invest in the US economy, it’s now.

“Without this kind of fiscal support, we’re going to leave a gaping hole in the economy,” Hersh said.

Congress is all but certain to fall short on the economy

It’s not hard to imagine a scenario where the Covid-19 pandemic played out much differently in the US. Had the country been able to get the coronavirus under control, and had Congress put in place economic supports that were predicated on metrics of recovery instead of hoping things would be fine by July or December, the picture in America might be quite different from what it is now.

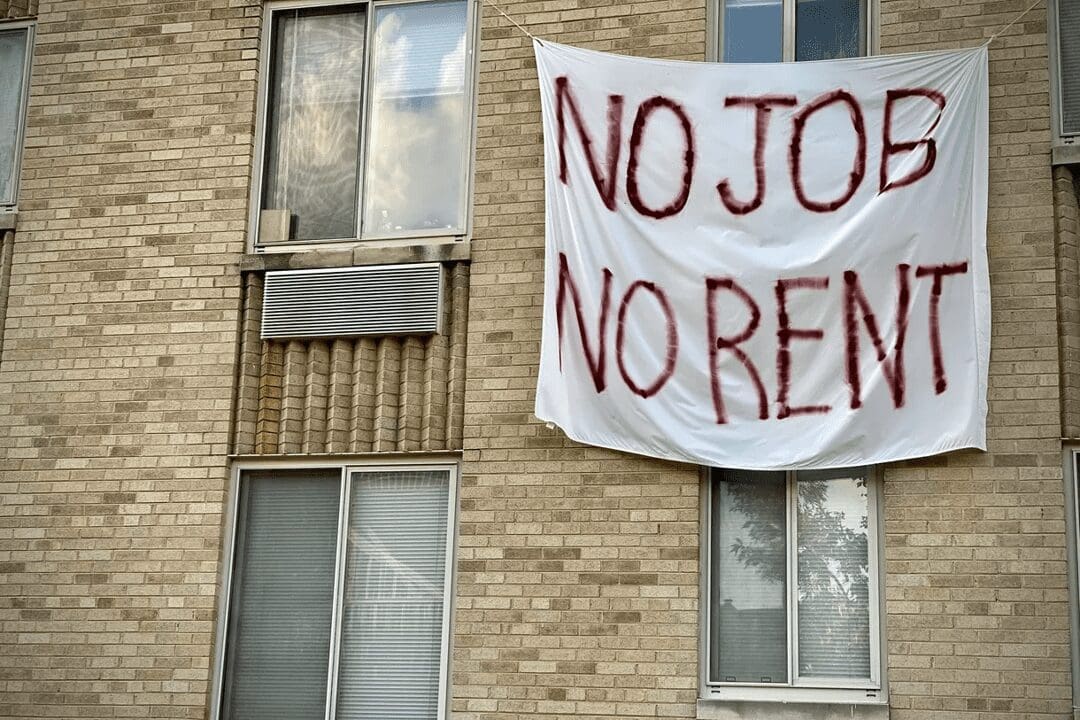

Instead, 2021 is just weeks away, and most of the mechanisms put in place under the first congressional stimulus package, the CARES Act passed in March, are about to expire or already have. An estimated 12 million Americans are poised to lose their unemployment insurance benefits on December 26, the day after Christmas. Tens of millions of people face possible eviction or foreclosure once a federal eviction moratorium expires on January 1. States and cities are facing enormous budget shortfalls. Student borrowers who have has their student loan payments put on pause are waiting month by month to see whether they’ll start to owe again.

With these crises weeks away, Congress is still haggling. Democrats in the House passed the $3 trillion HEROES Act — on the low end of what Hersh and Paul believe is needed to really help the economy — back in May, but beyond that, there just hasn’t been much progress. The Senate never voted on the HEROES Act, and Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell seems reluctant to get on board with much of anything. There’s hope in the new $908 million bipartisan proposal, but it’s hard to believe that will be enough.

Ultimately, the economy is made up of people, people are hurting, and lawmakers aren’t helping them. Past recessions have made it clear that recovery can take a long time, meaning today’s inaction will be a drag on the country, and financial problems for its people, for years to come.