Article originally published April 26, 2019.

Up to 60% of millenials (soon to be the largest living adult generation) consider themselves entrepreneurs, and yet less than 4% are currently self-employed. The number of young people that start companies has been steadily declining since the mid-90s. In 1996, young people launched 35% of startups. By 2014, this number was down to 18 percent.

In fact, we haven’t seen a measurable increase in entrepreneurial activity in over 40 years, with the rate of new businesses as a percentage of all U.S. companies dropping by 29% between 1977 and 2016. While economists and policy makers might argue over the reasons behind this stagnation, as with any normal distribution curve, the obvious answers lie in the short tail.

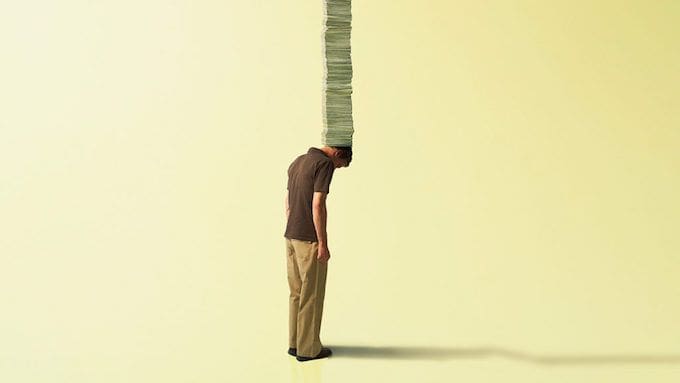

More than 44 million Americans collectively have over $1.5 trillion in student debt, $521 billion more than total credit card debt.

Over time, the mounting pressure from this growing debt crisis coupled with slowing wage growth has likely instilled fear among younger generations. Simply put — they’re far more averse to the risk that comes with trying to create something new.

When the majority of college graduates (nearly 70%) leave school with an average of $29,800 in debt, the thought of doing anything but getting a well-paying job to try to reduce this burden might seem irresponsible, at best. Even if one does land a job that affords them the luxury of steady loan repayment, they are likely to continue to pay off their loans for many years. Research from Citizens Financial Groupsuggests that 60% of student debt borrowers expect to be paying off their loans into their 40s.

While normalizing the cost of tuition might be the long term answer, in the short term, the power to reignite innovation and entrepreneurial venture creation lies within the parties that help pay the bills of most individuals and entities: employers and capital providers.

Employers can help put us back on track

To start, the relationship between employers and employees needs to adapt to the changing needs of the modern workforce. Job security is no longer enough to satisfy the new workforce, jaded by false promises of guaranteed opportunities after college. Employers competing for the best talent need to recognize this trend, and double down on treating employees as an investment and not an expense.

As with any investment that promises healthy returns over time, it’s important to look at things at the macro level. Today, most companies are optimizing for rapid productivity — hiring employees who can do their work as quickly as possible while also bringing in enough profit to pay for themselves as quickly as possible. But truly investing in your workforce may mean forgoing certain short-term gains in order to prosper in the long run. Forward-thinking institutions prioritize the well-being of their constituents.

What does this mean in practice? You have to start with what the majority of people value most — stability and freedom of choice. Solve the former, and you’ll enable the latter.

Today, student debt is the biggest contributor to the financial burden of the adult population. Providing employee benefits that alleviate this burden beyond the current loan forgiveness programs available (which a very small percentage of people are eligible for), could be the first step towards creating a sense of stability for your employees.

Fortunately, some companies are already taking the lead on this, making student loan and college savings benefits available to their workers. Companies like Fidelity Investments and Aetna offer their employees up to $2,000 a year toward repayment of their student loans by partnering with organizations like Tuition.io and Gradifi to administer these benefits. This practice is likely to spread to more organizations as it becomes increasingly evident that a salary alone isn’t enough to recover the cost of a college education, the very education that almost every employer today requires.

While in the short term this may translate into a slight increase in the overall payout to each new employee, in the long run organizations that are able to attract the best talent will win. Even if some of these employees go on to start their own businesses, they will be more likely to partner with or even refer high quality talent from their networks to the companies that invested in them.

If programs like this become normal practice over time, they could inspire a renewed sense of confidence among the Millennial workforce and the generations that follow, leading to a renewed tolerance for risk — something that’s required for innovation to flourish. After all, if Phil Knight had to worry about decades of student debt repayment, he may have never taken that trip to Japan shortly after graduating from business school which lead to the founding of Nike.

Capital funders will have to change or adapt their funding practices

To sustain a growing and diverse set of entrepreneurs and innovators, new sources of funding will need to become available. Today, most of the available investment capital ends up in the hands of a very small percentage of new ventures and initiatives. In the field of science and research, particularly, funding is typically reserved for PhDs that have the full backing and support of major institutions and the ecosystems they provide.

But, as observed by Patrick Collison of Stripe and economist Russ Roberts, many of the world’s most impactful contributions to science came from people that made their discoveries outside of this normal structure. Think of Nikola Tesla toiling away at his personal lab, or Albert Einstein sneaking away from his responsibilities as a patent clerk. Making funding available to a wider group of people that follow less traditional paths is critical for innovation.

In the area of commercial venture capital, access is even more limited. In 2017 alone, VC firms invested $61 billion in new capital, a sizeable number until you realize that it went to less than 1% of all ventures created that year. The rest of the 99% were funded through more common means — credit card loans, bank loans, money from friends and family, and side income (aka consulting projects).

Clearly, more debt isn’t the way to go, so what other sources of capital are there?

Many funds are starting to rethink the standard VC model of injecting massive amounts of capital to accelerate growth across a relatively small set of companies in the hopes that one or two “unicorns” will recover losses from all of the remaining investments. This model is simply not aligned with what most entrepreneurs actually need — steady and sustainable growth.

New kinds of capital are already becoming popular among entrepreneurs that don’t see the traditional equity-based VC model as the right path for them. Organizations like RevUp Capital offer revenue-based financing and funds like Indie.vc make equity investments that companies can repay over time as a percentage of their profits. While these new models are a great start for organizations that are already generating revenue, there are still more opportunities for innovation to fund earlier stage investments that are inherently riskier.

The education sector is developing new models that capital investors can learn from. The Lambda School, for example, gives students the option to enter into Income Sharing Agreements. Students agree to pay back tuition costs as a percentage of future income, in place of taking on more student loans. A similar model might work for people that want to start companies — agreeing to pay back investors through a percentage of their future income, or perhaps through shares of their future companies.

The first step to making any change is awareness of the problem, followed by education, and finally, action towards a resolution. While the pace of innovation is not defined by any one opinion or belief, it is influenced by our collective actions. Employers, investors, entrepreneurs, and educators all have a role to play in re-igniting innovation. Younger generations deserve to have a fair chance at the starting line — our future depends on it.