The nature of poverty in rich countries has changed. The sort of material deprivation common in developing nations is effectively a thing of the past. But millions of Americans lead precarious lives — always on the verge of getting evicted, not knowing where their next meal will come from, or unsure how they’ll be able to generate an income. This precarious existence has replaced abject deprivation as the fundamental marker of poverty.

Many believe such lifestyles are the result of low effort or poor individual choices. If people would simply follow the so-called success sequence — delay marriage and childbirth, stay in school, work hard, and so on — they wouldn’t fall into poverty. According to this view, welfare programs such as food stamps, housing vouchers or basic income are counterproductive, because they discourage the effort and perseverance that poor people need in order to lift themselves up by their bootstraps.

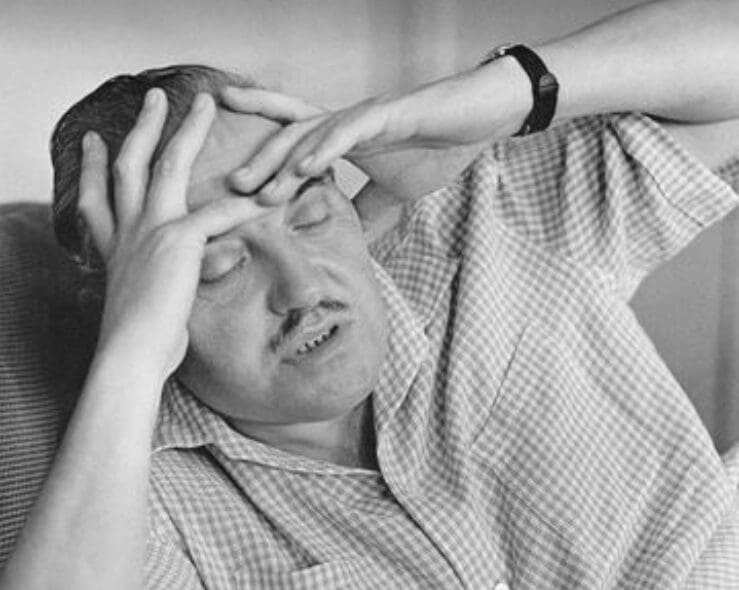

But this idea probably relies on a deep misunderstanding of what the lives of poor people are like. Economists are starting to accumulate evidence that instead of being indolent layabouts, poor people are harried and frantic. To deal with a world of precarity, where any misstep or piece of bad luck can lead to disastrous consequences, requires a massive amount of cognitive effort. And it’s the stress of that constant effort, rather than bad morals or welfare-inspired laziness, that drives many poor people to make subpar decisions.

Economist Sendhil Mullainathan of Harvard University has been at the forefront of the effort to better understand the challenges of poverty. In 2013, along with co-authors Anandi Mani, Eldar Shafir, and Jiaying Zhao, he published a groundbreaking paper entitled “Poverty Impedes Cognitive Function.” They found that when low-income shoppers in New Jersey thought about their finances, their cognitive performance went down. But that didn’t happen for higher-income subjects. This suggests that stress taxes the mind more than finances. In a second experiment on Indian farmers, they found that cognitive performance is worse before a harvest, when finances are tight.

Mullainathan expanded this result into a general theory of poverty. Scarcity, he believes, begets stress, which leads to bad decisions, which creates even more scarcity. Thus, poor people get trapped in an exhausting but inescapable cycle of precarity.

Before this theory can become conventional wisdom, it needs more evidence. A number of recent studies of poor people in developing countries (though not all of them) have found similar effects. In a 2019 paper, Mullainathan, along with economists Supreet Kaur, Frank Schilbach and Suanna Oh, discovered that Indian contract manufacturers boost their productivity right after they receive a cash payment. Mani and co-author Guilherme Lichand, studying farmers in a poor region of Brazil, found that both actual droughts and being forced to think about droughts reduce cognitive performance.

And in yet another recent paper, economists Vojtěch Bartoš, Michal Bauer, Julie Chytilová and Ian Levely found that when Ugandan farmers are primed to think about poverty-related problems, they become more likely to seek out entertainment and delay work. Thus, even when poor people avoid effort, it can be due to stress rather than complacency.

So evidence is starting to pile up in favor of Mullainathan’s theory. But these studies generally involve either lab experiments — which may not apply to the real world — or studies of developing countries. To really be certain that this is how poverty works, economists will need evidence on the everyday behavior of poor people in developed nations. Researchers might, for example, use the random timing of government stimulus checks to see if an infusion of cash made poor people less likely to make bad decisions.

Assuming the theory holds up, it has important consequences for how governments try to alleviate poverty. Instead of being conditional on work — which simply adds one more source of stress and risk — welfare benefits should be unconditional. The assurance of a basic income check each month, as well as guaranteed benefits like health care, would remove a lot of poor Americans’ cognitive load and allow them to re-focus on getting themselves out of poverty rather than simply surviving from day to day.

The U.S. also needs to reduce the transaction costs that add stress and hassle to poor people’s lives. Irregular working hours should be replaced with regular schedules. Perhaps marijuana should be at least decriminalized, if not legalized. And maybe cash bail should be abolished for nonviolent crimes. It should be easier to get a government-issued ID card. Police in poor neighborhoods should reduce the number of tickets given for minor infractions such as broken brake lights or slight speeding. Eviction should be more difficult.

These are just a few of the ways the U.S. can make life less of a hassle for its precarious poor.