Increasingly, economists are discovering that government spending on programs like healthcare and cash aid is an investment that pays future dividends, refuting old assumptions about the efficiency of welfare spending.

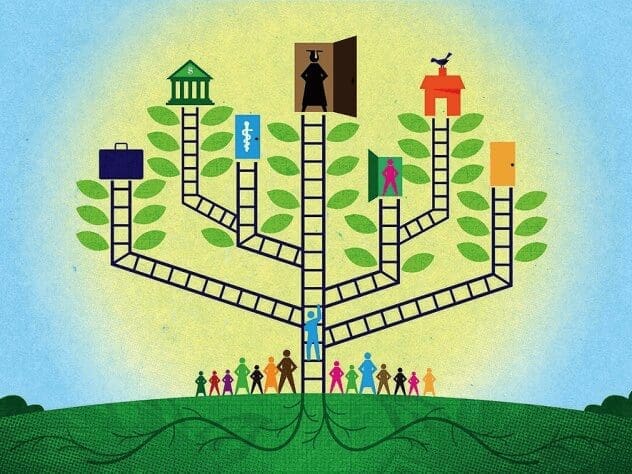

Increasingly, economists are discovering that government spending on programs like healthcare and cash aid is more than just humane policy. It’s also an investment that pays future dividends, refuting old assumptions about the efficiency of welfare spending.

Professor of economics Nathaniel Hendren is one of the young scholars at the forefront of research on the long-term consequences of welfare spending.

In a paper published earlier this year, he and economics doctoral student Ben Sprung-Keyser used data from 133 U.S. tax-and-spend policies implemented during the last half-century to argue that many such programs more than make up their cost to taxpayers over time.

That’s especially true for programs designed to lift low-income children out of poverty. Spending on services like Medicaid expansion, K-12 education, and college financial aid, they found, reduces long-term medical costs and makes children more likely to attend college, find high-paying work, and pay more in taxes as adults. “From a taxpayer perspective,” the authors write, “these expenditures on children are investments, rather than just transfers.”

The payoff for children’s programs is so dramatic, the paper suggests, that it may not make sense to think of them as “spending” at all.

A 2016 study by Hendren and Harvard economists Raj Chetty and Lawrence Katz, for example, found that giving low-income families vouchers that helped them move to lower-poverty neighborhoods substantially improved college attendance rates and lifetime earnings for their children. Spending to support adults can have a similar effect. In one example, states across the country between 1979 and 1992 expanded Medicaid to pregnant women, giving them better access to prenatal care. That policy change reduced future hospitalizations for their children, increased college attendance, and ultimately raised incomes. By the time their children were 36 years old, according to the new paper, increased tax revenue attributable to their higher earnings had already made up for the cost of the Medicaid expansion (about $3,473 for each mother).

One of his goals, Hendren explained in an interview, was to compare the benefits of different types of welfare programs, to help policymakers better understand which ones to prioritize, and why. “In the last 30, 40, 50 years, there’s been a really big advance in empirical work that has sought to identify the causal effects of government policy changes,” he says. But when government resources are limited, as they always are, making comparisons among the relative benefits of investing in education or food stamps or children’s medical care becomes more complicated.

“What we wanted to do in this work was to try to put everything on a level playing field,” Hendren says. “And for each of these different policies, we wanted to calculate: for every dollar that the government spends, how much benefit did it provide to the policies’ beneficiaries?”

It’s understandable that investments in children’s health and development are particularly likely to pay for themselves. But that doesn’t mean that spending on disability payments or unemployment insurance, which don’t usually raise more tax revenue for the government and aren’t designed to, are a less important use of taxpayer money. “There are a lot of policies that have low payoff to taxpayers, but you still might want to spend the money,” Hendren says. “My favorite example of this is disability insurance for kids.…We might be willing to spend money to make sure that disabled children in our population don’t starve.” While his research is a useful yardstick for quantifying the trade-offs between different safety-net programs, it’s not meant to be the only criterion used in policymaking.

Indeed, a major caveat is that state or city governments that provide for their populations’ needs may not reap the rewards of their investment. A child who grows up poor in Youngstown, Ohio, and moves to New York for better work opportunities might see a boost to her income, but none of that will accrue to her home state as tax revenue. Even children who do stay in their hometowns, Hendren stresses, will pay most of their taxes to the federal government, not to the local and state governments that decided whether to invest in high-impact programs like Medicaid, K-12 education, and subsidized housing.

Now, as state and city governments face a crushing fiscal crisis in the wake of the pandemic-induced economic crash, they have even fewer funds to spend on social policies that pay off in the long term. That exacerbates what Hendren calls “the fundamental problem” with the structure of U.S. social spending: that investment “happens at a state level, but all the benefits accrue at a federal level. It’s really a fiscal federalism problem. That’s one of the things I’m hoping we can fix,” he adds, “so that places like Youngstown have the right incentives to make these investments right now.”