The earned income tax credit is the leading example of smart centrist policy. In the 1980s and early 1990s, the U.S. saw bruising political battles over antipoverty policy, with conservatives charging that welfare discouraged work. In response, centrists cooked up the EITC as a compromise. Because the credit doesn’t give any money to people who don’t work, it is immune — at least in theory — to conservative criticism that it encourages laziness. In fact, because the EITC payment increases the more you earn, up to a certain threshold, it tends to encourages people to go to work:

Giving Credit Where It’s Due

The earned income tax credit rises with income, then phases out*

See the interactive chart here.

For parents with more children, the maximum payments are higher.

So the EITC fights poverty two ways — by giving poor people cash, and by encouraging them to go to work. They thus satisfy both liberal and conservative impulses. Meanwhile, the evidence has always seemed to be strongly on the side of the EITC. Economists Hilary Hoynes and Ankur Patel have found that EITC expansions tend to reduce poverty significantly among single mothers. There’s also evidence that EITC increases health and happiness for mothers and educational attainment for children. A 2015 review of the research literature by economists Austin Nichols and Jesse Rothstein appeared to confirm these findings.

Thus it’s unsurprising that the EITC has been increased repeatedly by both Democratic and Republican administrations over the years, even as other welfare programs have been scaled back under attack from the right. An EITC-like plan is at the heart of Senator and presidential candidate Kamala Harris’s economic program, and various states have been implementing their own EITCs.

However, just because the EITC is successful doesn’t mean it’s the best possible approach to combating poverty. The biggest criticism of the program is that it doesn’t give money to those who don’t work. First of all, this excludes people who are simply unable to work, due to disability, illness age, or the simple inability to find a job (these people may be eligible for other benefits, like Social Security and Social Security Disability, but not always). Second, it doesn’t reward parents for child care, elder care, and housework, which are valuable activities even though they aren’t compensated monetarily. This suggests that instead of phasing in benefits as people earn more, the government should simply pay a lump sum to everyone who makes less than a certain threshold — a basic income for the poor.

Defenders argue that the EITC, unlike a basic income, encourages people to go to work. And there seems to be plenty of evidence that it does. Nichols and Rothstein report:

Essentially all [researchers] agree that the [1993] EITC expansion led to sizeable increases in single mothers’ employment rates, [especially] less-skilled women and…those with more than one…child.

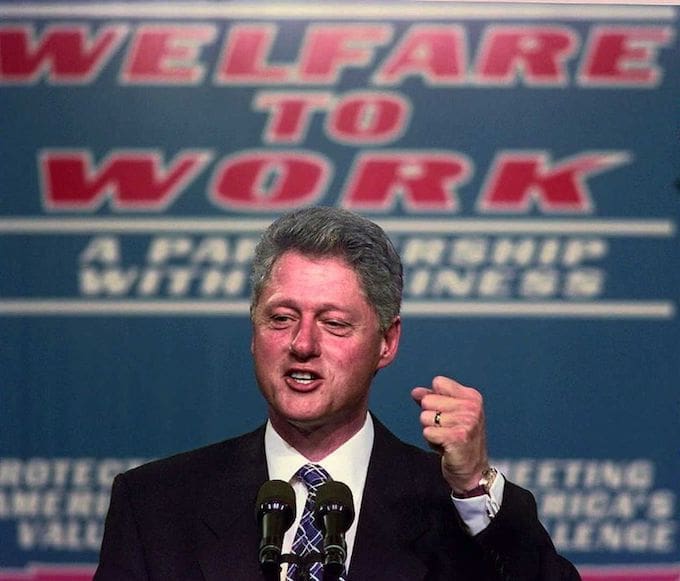

However, as Nichols and Rothstein note, most of the studies showing that the EITC puts single mothers to work is based on one single event — the big increase in the program under President Bill Clinton in 1993. But as the authors point out, there were other things happening in the ’90s — for example, welfare reform in 1996, which pushed single moms to get jobs. They argue that these other policy changes might also have given greater work incentives to moms with multiple kids, thus mimicking the expected labor supply effects of the EITC, which gives higher payments to people with more children.

Nichols and Rothstein believe that despite this possibility, the evidence that the EITC encourages work is still fairly robust. But in a recent presentation, Princeton University economist Henrik Kleven argued that this isn’t the case.

Kleven notes that the increase in labor-force participation for mothers with three children in the mid-1990s was much greater than for women with only two children, even though the EITC payment was only slightly higher for the former. He also points out that there appears to be no effect on married mothers, and that smaller EITC increases in other years don’t appear to have any visible effect on women’s labor- force participation. These all suggest other factors at work in the ’90s, such as welfare reform and the strong economy.

Kleven also reviews state-level EITC programs. Comparing each state that increased the EITC substantially to others that did not, he finds that these programs don’t appear to have successfully pushed people to get jobs.

If Kleven’s results are right, it deals a devastating blow to the idea of the EITC as a work incentive. It is worth noting that Kleven’s finding contradicts that of a 2001 paper by Bruce Meyer and Dan Rosenbaum and of a 2019 paper by David Neumark and Peter Shirley, both of which also look at state-level EITCs. Only time, and extensive debate, will clarify who is right.

But if it turns out that Kleven has it right, then that means the EITC needs reform. If benefit phase-ins don’t encourage the able-bodied to work, then the moral imperative of giving payments to the disabled and elderly, and of rewarding unpaid child care, clearly take precedence. In that case, the best program would be one that simply pays a basic income to all poor people.