By: Isabelle Kirk.

See original post here.

A universal basic income (UBI) is a fixed payment, paid equally by the government to every citizen of a country, regardless of whether they are in work. The pandemic saw the advent of payments similar to a UBI – ‘stimulus checks’ in the US, for example – and some countries have conducted experiments with basic income programmes.

People in favour of a universal basic income argue that all citizens deserve a decent standard of living and propose that a UBI could radically reduce poverty. A universal basic income is not means-tested. While this means that recipients are not required to jump through hoops or face the stress and uncertainty of a non-guaranteed benefit, it has also been argued that it is unfair as it’s paid equally to everyone, including wealthy people who do not need it.

Do Europeans support introducing a universal basic income, and what level should it be set at?

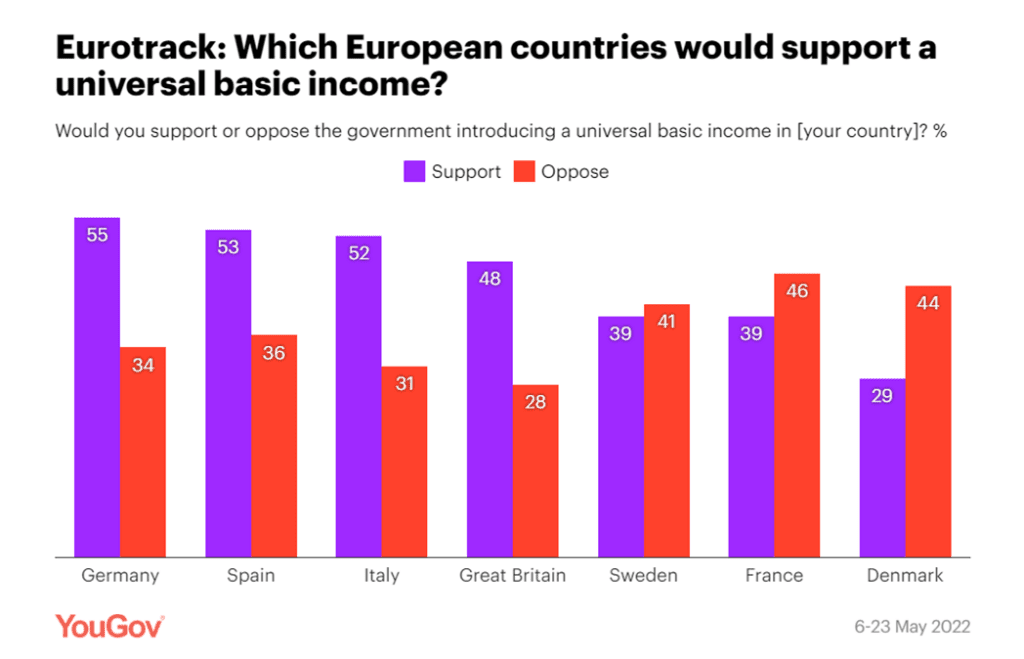

YouGov’s Eurotrack shows varying support for the introduction of a universal basic income across seven European countries, with support being highest in Germany (55%) and Italy (52%) and lowest in Denmark (29%).

Great Britain, Germany, Spain and Italy are all more in favour of a basic income than against it, with Sweden split, and France and Denmark more opposed.

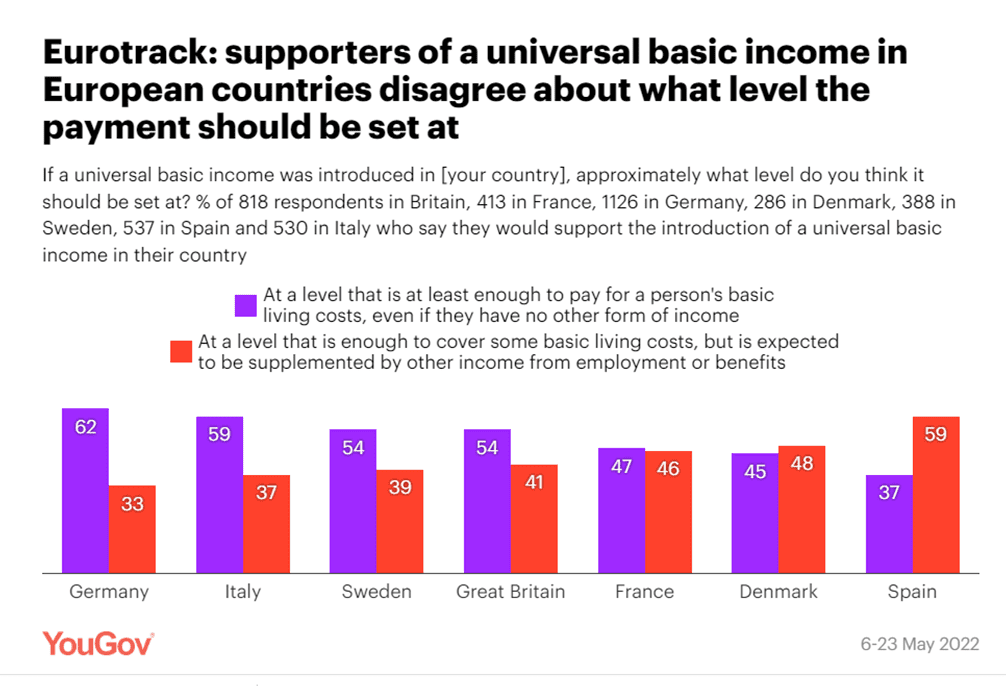

For those who support the introduction of a UBI, the question then becomes what level the payment should be set at. Finland’s universal basic income experiment, conducted in 2017-18, set the level at €560 (£490) a month, but the main debate centres on whether a person should be able to survive wholly on a universal basic income, or whether it should be supplemented by other forms of income.

Supporters of the scheme in European countries differ on what level the payment should be set at. Six in 10 Germans who support a basic income say a UBI should be set at a level that is at least enough to pay for a person’s basic living costs (62%), even if they have no other form of income. This view is shared by 59% of Italians and 54% of Britons and Swedes who support introducing UBI.

In Spain, 37% of supporters of a UBI favour this basic costs-level, but the majority (59%) would set it lower than this: at a level that is enough to cover some basic living costs, but is expected to be supplemented by other income from employment or benefits. French and Danish supporters of a UBI are split.

Can governments afford the cost of a universal basic income?

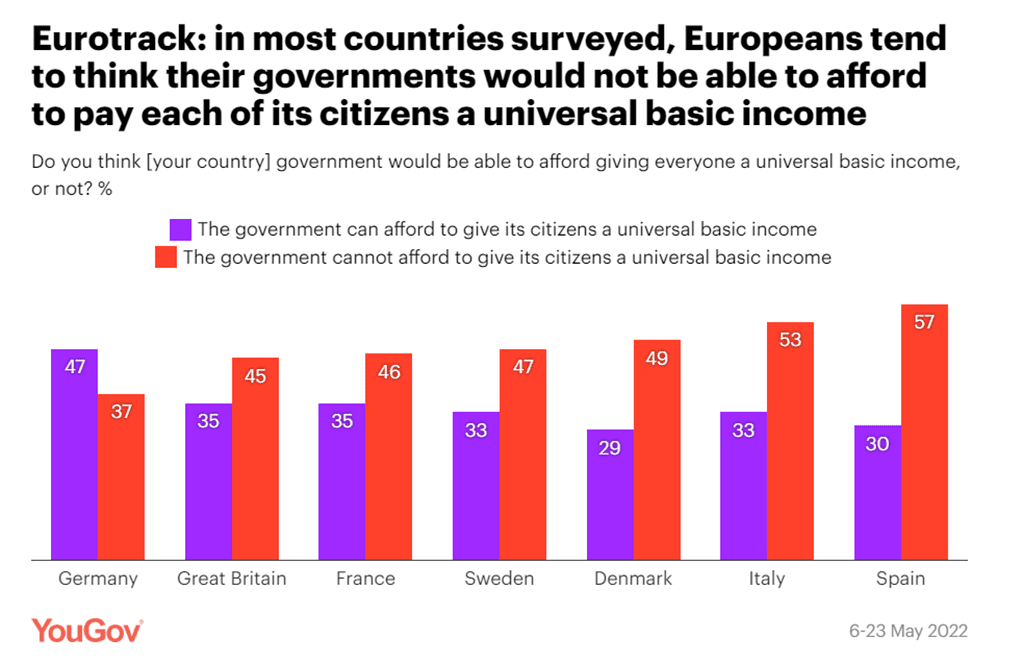

A major argument against the introduction of a universal basic income is the cost of the scheme. In the UK, estimates of the cost of a UBI range from £67 billion a year (the cost of the Covid-19 furlough scheme) to £427 billion a year. For a basic income that every individual can survive on, money could be raised from axing benefits entirely, but the scheme would nevertheless be exceptionally expensive in order to give a liveable wage to every citizen.

Despite high levels of support for the policy itself in some of the countries, all nations polled (except Germany) felt that their governments could not afford to give citizens a basic income. On average, 48% of Europeans felt that a UBI was too expensive, with Spain most emphatic – 57% say the Spanish government could not afford to give its citizens a basic income, with 30% saying they could afford it.

How would a universal basic income impact quality of life, poverty, work, and economic growth?

From existing pilot schemes, there is evidence that introducing a universal basic income would improve quality of life and well-being, radically reduce poverty and actually improve employment levels. Opponents of the scheme argue that a UBI undermines incentives to participate in work, and the Institute for Policy Research states that it is “impossible” to design a UBI that controls cost, meets needs and maintains work incentives.

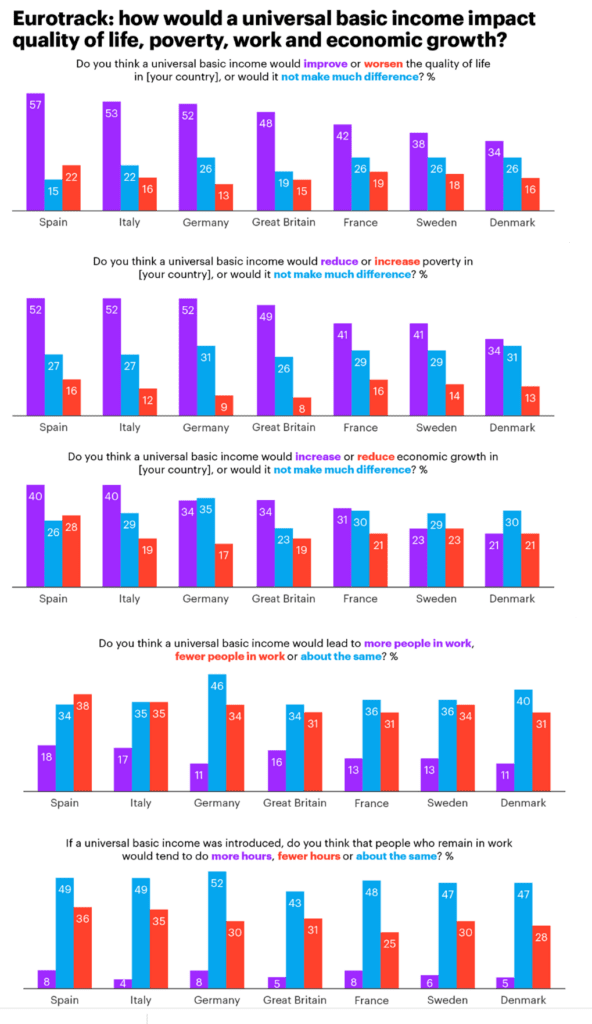

All countries polled in our survey were more likely to say a UBI would improve quality of life than worsen it, with Spain (57%), Italy (53%) and Germany (52%) most convinced. Between 13% and 22% of Europeans in our survey say a UBI would worsen quality of life, while 15-26% think it would make no difference to quality of life.

Similarly, between 34% and 52% of Europeans say a UBI would reduce poverty, while 8-16% say it would increase poverty and 26-31% say it would not make much difference. People in Denmark, which has lower support for the policy in general, are least convinced that a basic income would improve quality of life (34%) or reduce poverty (34%).

On the subject of work and economic growth, Europeans are less sure. Spaniards (40%) and Italians (40%) are most likely to say that a basic income would increase economic growth, while Danes (21%) and Swedes (23%) are least likely to have this view. However, there is more consensus in these countries that a UBI would not make much difference to economic growth (30% in Denmark, 29% in Sweden) than reduce growth (21% and 23%).

All countries polled did not think that a universal basic income would lead to more people in work, with most saying it would lead to about the same number of people in work, or fewer people in work.

For people who remain in work, Europeans tend to think they will do the same number of hours, with between Germans (52%) most likely to have this view. Few think that workers would take on more hours, while 25-36% think that people who remain in work would do fewer hours if a UBI was introduced.

See international topline results here and UK demographic results here