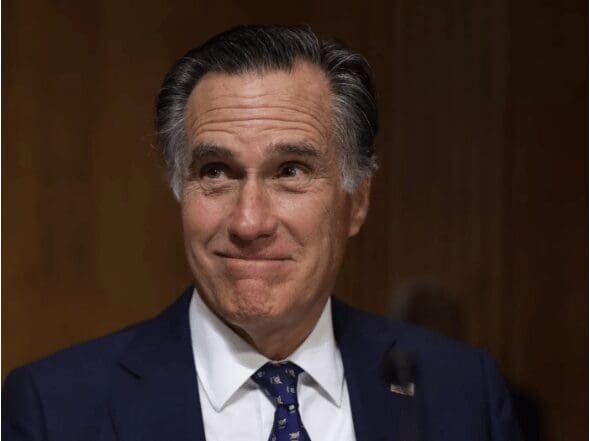

On Sunday, Sens. Mitt Romney (R-UT) and Michael Bennet (D-CO) announced a bipartisan plan to do something pretty extraordinary: establish a basic income for children in the United States.

The plan is relatively modest. Parents would get a guaranteed $1,500 in cash every year per child under the age of 6, no matter their income, and $1,000 per child aged 6 to 17. Another $1,000 in benefits per child, regardless of age, would phase in with income, as occurs under the Child Tax Credit already in the federal tax code.

Right now the Child Tax Credit is only refundable for people earning at least $2,500 per year, and even then, phases in gradually with earnings and is limited to only some of the credit. The result is that the poorest Americans — like disabled parents, or parents who don’t have any cash income — are cut off from the benefit, and parents working for low wages or low hours don’t get the full benefit.

Under Bennet/Romney, the full benefit would still be reserved for working parents. But for the first time in American history, the poorest parents would be guaranteed a benefit whether or not they are employed.

While the proposal hasn’t been formally analyzed yet for its impact on poverty, analysis of earlier, more generous proposals by Bennet and allies for a universal child allowance suggests this plan would reduce child poverty by millions of children, and make it less severe for millions more. A recent National Academy of Sciences report on child poverty found that an American child allowance would be an evidence-based, high-impact way to cut the child poverty rate.

Romney and Bennet would pay for the change in part by repealing “stepped-up basis.” That’s a federal tax rule that greatly reduces the taxability of inherited property. It says that if, say, wealthy art collector Milburn Pennybags Sr. buys a painting for $10 that is worth $1 million when he dies years later, then Milburn Pennybags Jr. can sell it for $1.1 million and only pay capital gains tax on the $100,000 it’s appreciated between inheriting it and selling it. Under Romney and Bennet’s proposed change, the younger Pennybags would have to pay tax on the nearly $1.1 million in value the painting gained since his father bought it.

Effectively, Romney and Bennet are proposing increasing taxation on the very wealthy to fund a benefit expansion directed at poor and working class families.

The Bennet-Romney proposal is offered in the context of an end-of-year congressional fight over a spending package and technical fixes to the 2017 Trump tax cuts law that Republicans desperately want. House Ways and Means Chair Richard Neal, the top House Democrat on tax issues, has been pushing for including two major expansions of benefits for poor Americans in the package: a provision making the $2,000 existing child tax credit fully refundable (that is, making it a basic income for kids), and an expansion of the Earned Income Tax Credit to include adults without children.

Republicans in the Senate, though, have historically been extremely hesitant to expand cash programs for the poor, and while making the child tax credit fully refundable has had some support in center-right intellectual circles, Romney is the first Republican senator to my knowledge to officially endorse the idea; others like Marco Rubio and Mike Lee have only endorsed limited refundability. The influential conservative think tank the American Enterprise Institute’s president Robert Doar and poverty scholar Angela Rachidi are notable, vocal opponents of the idea on the grounds that it might discourage work (an argument which research on other countries’ child benefits suggests is false).

That makes the proposed Romney-Bennet compromise so exciting: it suggests the dam has broken and there is now space for actual Republican politicians to support a true child allowance. Senate leadership may yet reject the deal, but Democratic control of the House means the Dems have leverage in pushing Republicans to accept some kind of fully refundable child benefit.

An aide to Bennet told me that as of early Monday morning, Romney remains the only Senate Republican to sign on to the compromise. But the situation is evolving fast, and Romney’s involvement increases the odds that some kind of refundable benefit makes it into the eventual bill.

Child allowances are the norm abroad but the US has been a holdout

A child allowance or similar policy exists in almost every EU country, as well as in Canada and Australia. In many countries, the payments are truly universal; you get the money no matter how much you earn. In others, like Canada, the payments phase out for top earners, but almost everyone else benefits. France has an unusual scheme in which only families with two or more children get benefits, as an incentive to have more kids.

But the core principle is the same in every system: Low- and middle-income families are entitled to substantial cash benefits to help them raise their children.

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6522525/Child-benefit-comparison.0.png)

This helps explain why European countries are so much better at fighting child poverty than the US. While about 11.8 percent of US children live in absolute poverty (as indicated by the US poverty line), only 6.2 percent of German children do, and only 3.6 percent of Swedish children do (note, though, that this absolute poverty data isn’t updated regularly and is a bit out of date).

The numbers become even worse when you define poverty like most European countries do, as living under half of the median income. By that standard, 20 percent of children in the US live in poverty, compared to only about 10.3 percent in Germany and 4.9 percent in the Netherlands.

This isn’t exclusively due to child benefits, but they play a crucial role.

For instance, in 1999, Tony Blair and the Labour Party dramatically increased cash benefits for families with children in the UK. But it wasn’t a standalone initiative. The measure was part of a broader set of proposals meant to tackle child poverty, including tax credits, means-tested programs, a national minimum wage, a workers’ tax credit, universal pre-K, expanded child care, and much longer parental leave.

The result was that absolute child poverty fell by more than half from 1999 to 2009, while relative poverty (the share of children under 60 percent of the median income) fell by 15 percent. The decrease in relative poverty was smaller because while things got dramatically better for the poor, the middle class gained, too.

While child poverty in the US declined slightly over the same period, a comparison of the two trend lines put together by Columbia University professor of social work Jane Waldfogel is still startling:

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/6484127/Screenshot%202016-05-13%2016.55.34.png)

After Blair took office in 1997, the child poverty rate in Britain began to plummet, and kept plummeting as the reforms were implemented through 2001. Then it continued to gradually decline. In the US, by contrast, child poverty fell with the late-’90s boom, and then rose in the 2000s.

The UK benefit and tax credit increases from 1997 to 2005 caused incomes for the bottom 10 percent of households to grow 20 percent, according to researchers Tom Sefton, John Hills, and Holly Sutherland.

While concerns over “welfare queens” living high on the hog and misspending benefits have often stopped the US from expanding safety net programs, there’s no evidence that child benefits would be used this way. Sam Houston State University’s Christian Raschke found that Kindergeld, the delightfully named German child benefit program, leads families to spend more on food but not to drink more alcohol.

One study of the US’s earned income tax credit found that receiving cash actually makes mothers more likely to get prenatal care, which in turn reduces the amount they smoke and drink. A Canadian study found that each dollar spent on child benefits reduced spending on tobacco by 6 cents and spending on alcohol by 7 cents.

What’s more, a growing body of evidence suggests that investments in early childhood development can pay off in lower crime, higher earnings, and greater educational attainment later on.

Programs that give families cash, according to UC Irvine economist Greg Duncan, result in better learning outcomes and higher earnings for their kids. One study found a $3,000 annual income increase for poor parents is associated with 19-percent higher earnings for their child once they grow up. That implies that a child allowance of that size could dramatically improve the lives of children decades later.

There’s plenty of other research where that came from:

- When the Eastern Band of Cherokee Indians’ casino began paying dividends to its members, psychological problems among children decreased, crime rates dropped, and on-time high school graduation rates increased, according to Duke University’s Jane Costello.

- Canada’s child benefit expansions boosted test scores and health outcomes, the University of British Columbia’s Kevin Milligan and University of Toronto’s Mark Stabile found.

- A short-lived universal child benefit program in Spain increased the time mothers spent with children in the first year of life, according to a study by Libertad González at Pompeu Fabra University in Barcelona, and reduced the risk of couples with newborn babies breaking up.

Cash subsidies can even extend lives. Brown’s Anna Aizer, University of Toronto’s Shari Eli, Northwestern’s Joseph Ferrie, and UCLA’s Adriana Lleras-Muney looked at the Mothers’ Pension program, the first federal welfare program in American history, which ran from 1911 to 1935. They found that male children of mothers who were accepted for the program lived one year longer, got more schooling, and had incomes 14 percent greater than children of mothers who were rejected.

A child benefit would even have some effects that social conservatives might like. It encourages having more kids, and would likely reduce abortion rates by making it less costly to raise children. Money troubles are also a leading cause of marital strife, family instability, and divorce. Endicott College sociologist Josh McCabe has argued for a universal child benefit in pieces for the conservative National Review on exactly these grounds.

McCabe’s argument is compelling but has not been enough to persuade existing Republican politicians to support a fully refundable credit. Romney’s support for the policy suggests this might be changing, however slowly.