See original post here.

New Zealand is suffering many of the same ills that afflict American cities. Tenants facing ever-rising rents, young people and ethnic minorities being priced out of homeownership, widening inequality driven by soaring land values, sprawling cities and congested streets. A long and bitter debate that blamed land use regulations for these problems has largely been won by ‘YIMBYs’, with several waves of upzoning producing a budding building boom for townhouses and apartments. While there are some signs that rents may be easing as a result, these problems are far from solved, and public attention has begun to look for alternative solutions.

One topic that has been tiptoed around for years is the tax system. Like the US, New Zealand has a tax system that largely favors property ownership, with capital gains and imputed incomes from homeownership not being taxed, and mortgage interest (previously) being deductible for property investors. As a result, effective tax rates for property ownership are significantly below those of alternative investment options, encouraging kiwis to funnel their savings into real estate. While successive tax working groups have endorsed land taxation as a solution to this problem, the current government has entirely ruled out the possibility of raising taxes on homeowners or capital gains in general. A desperate scramble to climb onto the property ladder remains essential for access to membership of the middle and upper classes.

It is therefore incredibly heartening that one of New Zealand’s minor political parties has now made land value taxation a central plank of their policy platform. While not currently in Parliament, The Opportunities Party (TOP) has been active since 2016, campaigning on a proposal to tax imputed incomes from homeownership. Unfortunately, this proposal does not differentiate between a house and the land underneath it, both of which it would tax in the same way. Here at the Center for Property Tax Reform, we have long presented evidence demonstrating the benefits of shifting taxes from improvements and onto land values. However, as New Zealand heads into an election in 2023, TOP has finally announced a bold policy platform that raises taxes on land values, cuts taxes on earned income, and ultimately redistributes revenues through a universal basic income (UBI). Though TOP face tough hurdles in their battle for a seat in parliament––they must receive over 5% of the national vote or see leader Raf Manji win his local electorate of Ilam in Christchurch, there are still many lessons to be learned from their proposals. TOP’s plan would roll out in two phases, which we analyze in turn.

Phase 1 of TOP’s plan combines a land value tax (LVT) with income tax cuts and additional support for the underprivileged. Residential land would face an annual tax of 0.75% on its market value. New Zealand already has an established statutory process for assessing the value of both land and buildings every three years, making it very easy to implement this LVT. A full cadastre of property ownership will make this LVT difficult to avoid, although the exemption of commercial land could lead to some distortionary behavior if some landowners seek to convert residential land to a commercial zoning. Other exemptions, including for rural, conservation and Māori land, are more justifiable and less prone to avoidance.

While this LVT is below 1%, it is expected to raise $7bn in revenue (US$4bn), equivalent to around 8% of existing tax revenues. TOP proposes to cut taxes on earned income (including by making the first $15,000 income entirely tax-free), expand support to people with disabilities by $400m, expand tax credits for low-income working families by $500m, and wipe $2 billion of debt currently owed to the Ministry of Social Development.

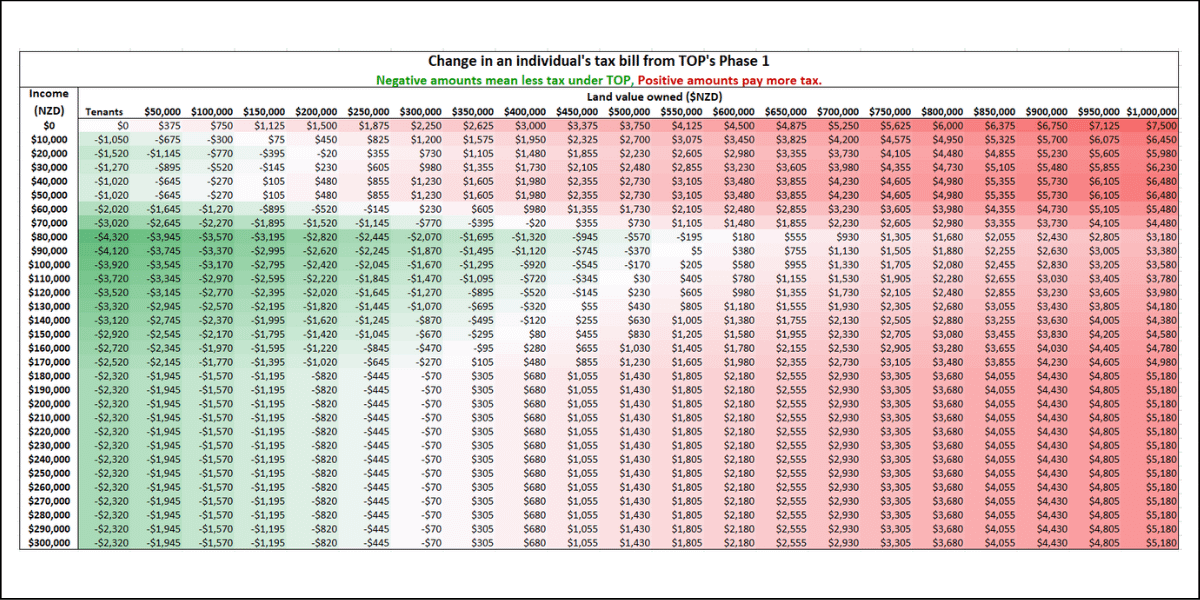

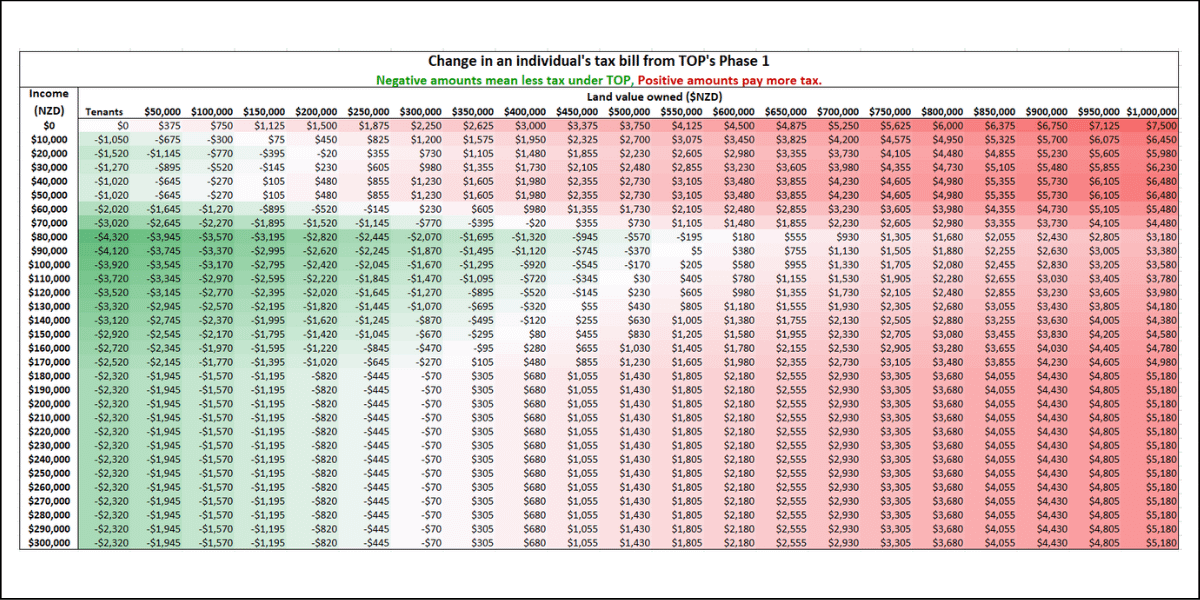

Here at CPTR, we have calculated how these tax changes will change the tax bills of individuals at different combinations of income and land ownership, which are presented in the figure below. For reference, the median household owns around $400,000 worth of real estate, of which around two-thirds is land. Split between two adults, each would own around $130,000 of land value. A person who is working full-time at the median wage earns around $63,000.

Here we can observe some striking benefits of using LVT to cut income taxes. Someone with the median combination of income and wealth described above will enjoy a $1,300 tax cut under Phase 1 of TOP’s Higher Incomes Policy. Every single tenant in New Zealand will keep more of their pay. If they are on the median wage, TOP’s Phase 1 will boost their after-tax income by $2,000 each year. Conversely, for those who own half of an average home in Auckland, which is worth $610,000 of land value currently, tax bills are guaranteed to increase. This is a good thing, since these homeowners have enjoyed nearly $450,000 of untaxed growth in land value over the past decade.

One point to note is that those people with low incomes will face a higher tax bill if they own real estate. On one hand this is entirely reasonable given that these households have recently seen significant unearned growth in their household balance sheets due to rising land values. It is also important to note that their tax bills will be directly proportional to the value of their land. However, some homeowners are truly stuck in a position of not having sufficient cash flow to pay their LVT, such as those who are retired or disabled. In these circumstances, CPTR would advise TOP to allow for tax deferral, whereby the tax bill is allowed to accrue against the property title and be paid when it is next sold.

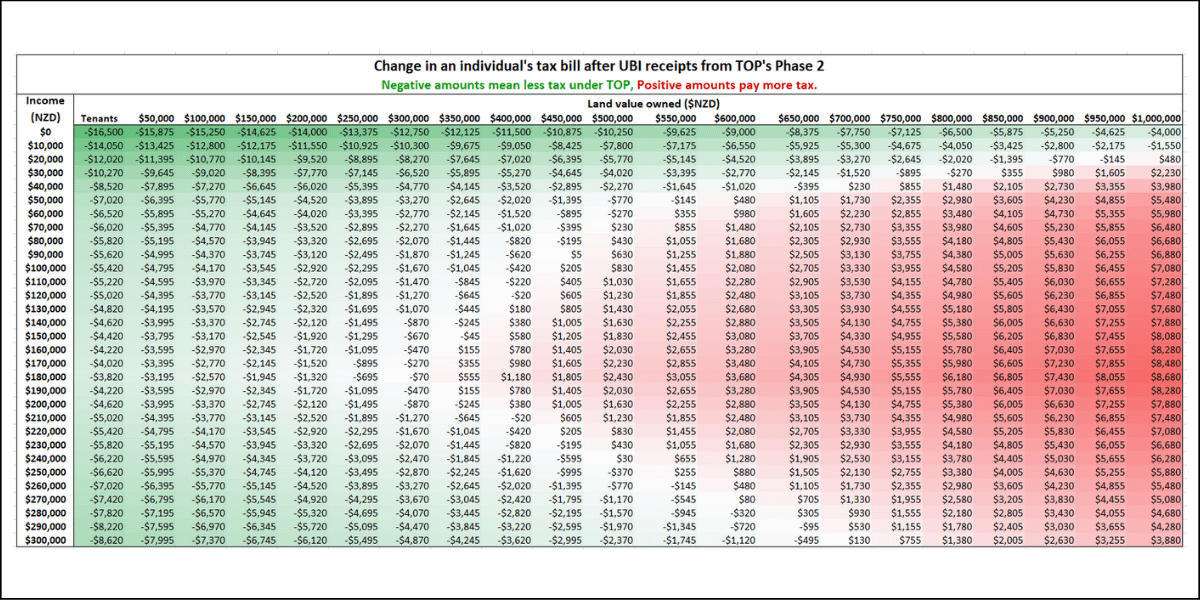

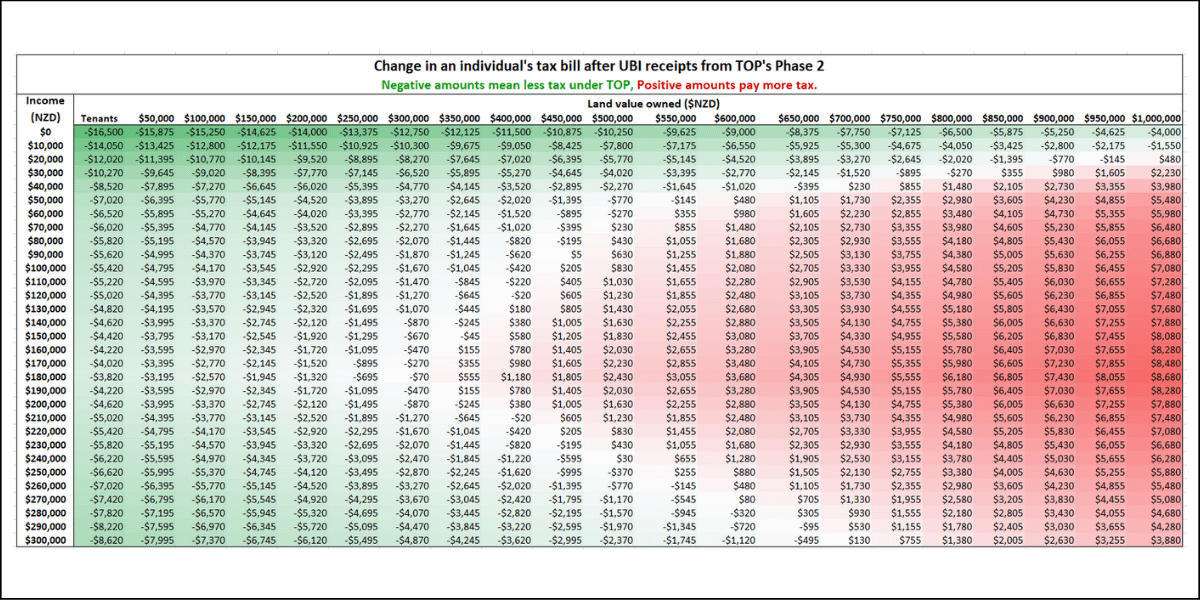

Phase 2 of TOP’s plan actually demonstrates an alternative solution to this problem: combining LVT with a UBI. For this final stage of their plan, TOP proposes to raise the LVT to 1.25% and simplify the rest of the tax system to a flat 35% tax rate on all earned income. Revenues will be sufficient to pay $16,500 a year to every citizen aged 18 to 65, with parents receiving $2,300 for every child under 18, and retirees continuing to receive superannuation payments. Below we depict how this proposal will impact tax bills, again by comparison to the current tax system.

We can immediately see how combining LVT with a UBI ensures that low income homeowners will have sufficient cash flow to cover their tax bill. People on low or no incomes will be better-off than they are under the existing tax system right up until they own $1.3m of land value. Likewise, tenants are universally made better-off by TOP’s Phase 2, with their annual income net of taxes being at least $3,800 higher than they are currently, and being $6,500 higher if they currently work full-time at the median wage. Someone with the median combination of income and wealth is made $4,700 better off. Tax bills will rise for those New Zealanders who own valuable land and earn high incomes, ultimately making the tax and transfer system more progressive than it is currently.

Thus, the policy platform of The Opportunities Party neatly demonstrates the options that are available when land rents are captured for the public good and deployed to cut income taxes or boost household incomes. New Zealand’s failure to meaningfully tax land has allowed wealth to flow from tenants and younger generations into the pockets of property owners, widening inequality and producing sclerotic cities. One crucial way to fight these forces is to raise taxes on land rents and redistribute these revenues through UBI payments or by reducing the taxes paid by workers.