By Joshua McCabe

See original post here.

After several months of negotiations, Ways and Means Committee Chair Jason Smith has released the details of the Tax Relief for American Families and Workers Act of 2024.

The proposed tax package includes several changes concerning business deductions, international trade, housing, and families. Specifically, it would make several changes to the child tax credit that address conservative concerns about work incentives and progressive concerns about distributional impact, which had held back previous efforts to come to a bipartisan consensus.

Currently, the credit has two components–a nonrefundable portion and a refundable portion–that ensure the credit phases in as household income rises. Families who have not earned any income in the past year are not eligible to receive the credit. The refundable portion provides families with a credit equal to 15% of their earnings that exceed an initial $2,500 earnings threshold (up to $1,600 per child). The remaining $400 can only be claimed as a nonrefundable credit.

The proposed tax package would make four significant changes.

First, it would speed up an already planned increase in the credit’s refundable portion. The 2017 tax reforms set it at $1,400 and indexed it to inflation so it would gradually rise yearly. Last year, it rose to $1,600. The proposal would retroactively raise it to $1,800 for 2023 and increase it by $100 annually until it reaches the total $2,000 in 2025.

Second, it would shift from a fixed phase-in per household to one that varies based on the number of children. The 15% phase-in rate currently applies to households regardless of how many children claim the credit. This increases the minimum earnings necessary to claim the maximum refundable portion of the credit for families with more than one child. A married couple with one child, for example, must earn at least $13,200 to receive the total $1,600. If they have a second child, they must earn at least $23,900 to receive the full $3,200 for both children. Under this proposal, the phase-in would shift from 15% per household to 15% per child after the same initial $2,500 earnings threshold.

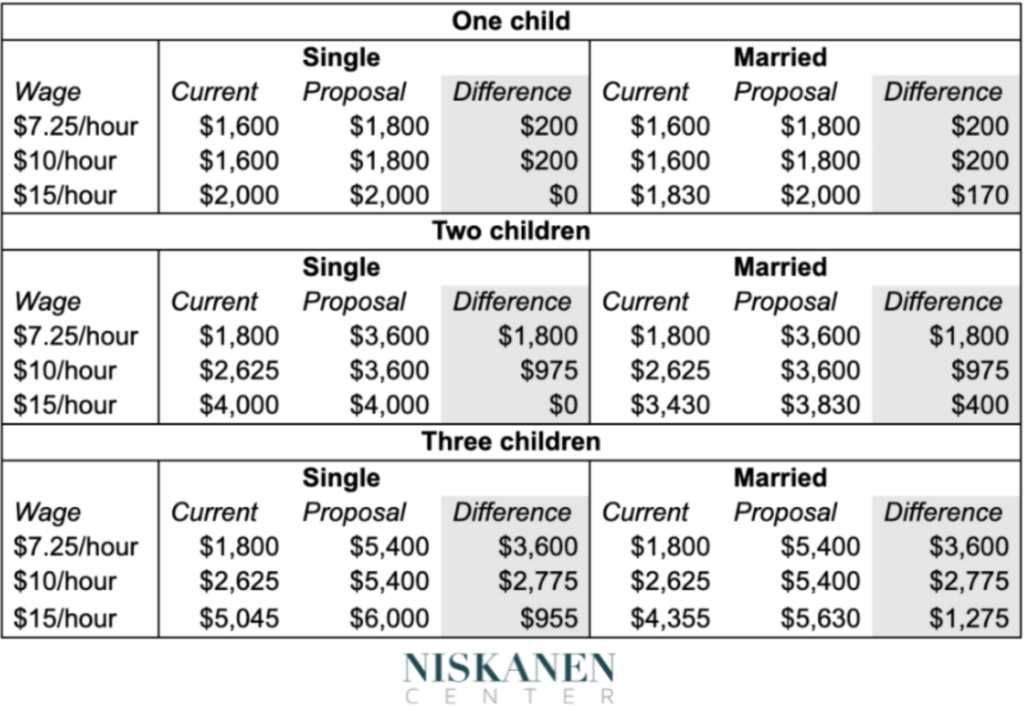

These two provisions would majorly impact low-income working families–particularly those with two or more children. Figure 1 looks at how the changes would impact households with one person working full-time at various hourly wages this past year.

Table 1. Total child tax credit amount under current law and proposed reform, 2023

This would effectively make any family working full-time at the federal minimum wage eligible for the maximum refundable credit amount – $1,800 for one child, $3,600 for two children, and $5,400 for three children. Larger families would see the most considerable increase in their total credits. For example, a minimum wage worker with three children would see their credit triple from $1,800 to $5,400 at tax time.

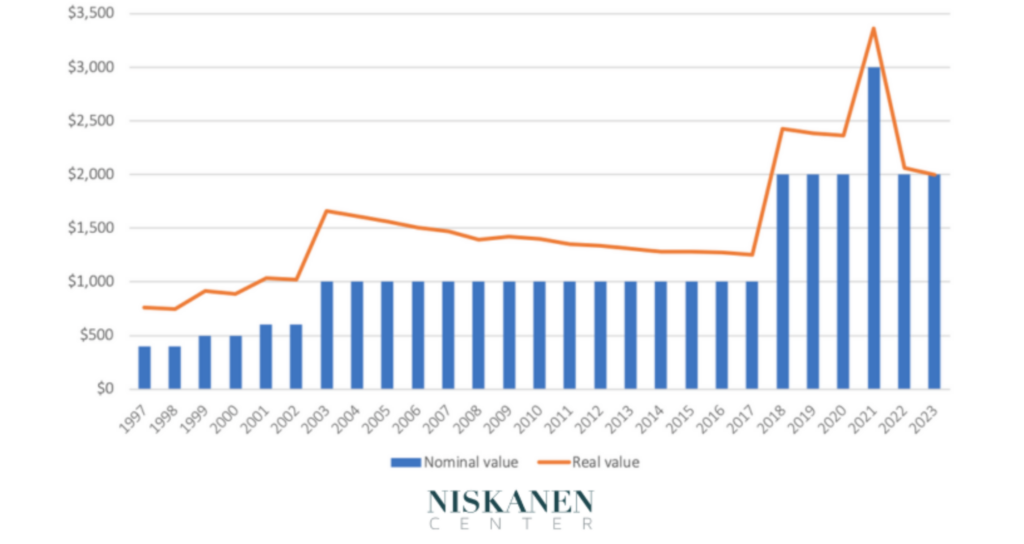

Third, the proposal would begin indexing the value of the child tax credit in 2024. Unlike most other family provisions in the federal tax code, the child tax credit is not automatically adjusted for inflation each year. As a result, the credit’s real (inflation-adjusted) value erodes each year unless Congress increases its nominal value. The recent spell of higher-than-usual inflation has led to a significant decline. If Congress had indexed the credit when it expanded it as part of the 2017 tax reforms, for example, it would be closer to $2,400 rather than the $2,000 it stands at today (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Maximum value of child tax credit, 1997-2023

The proposed indexation will not reverse this previous erosion but will prevent it going forward. This will be particularly important for middle-income families who have borne the brunt of the erosion.

Lastly, the proposal will allow families to choose between the current or previous tax year when calculating their earnings to determine their credit amount. Under current law, families must use their current year’s income to determine how much credit they can receive during tax time. Because annual income can be volatile, particularly for low-income workers, families could see their total credit swing up or down from year to year. Under the proposed reform, for example, a worker whose annual earnings drop from $15,000 in one year to $10,000 the following because his hours were cut could still claim the maximum refundable portion of the credit by “looking back” to his previous year’s earnings and using that to calculate the credit.

If Congress is looking for a way to help struggling families, these four proposed changes would provide low-income working families with a much-needed boost to support them with the cost of raising children.