Proponents say no-strings-attached payments can boost urban development, narrow the racial wealth gap outside of emergencies too

by Carey L. Biron | @clbtea | Thomson Reuters Foundation

Highlights:

> Controversial plans are seen as effective and equitable ……

> Cities increasingly experimenting with cash handouts …….

> Pandemic has fueled policymakers’ interest …..

WASHINGTON, April 20 (Thomson Reuters Foundation) – Handouts lead to laziness and breed dependency, according to the critics. Advocates counter that cash can lift the left-behind out of poverty. What better time to test it out than a pandemic?

A high-stakes experiment is underway in a deprived corner of the U.S. capital, with backers eager to see what happens when poor Americans are given cash payments for a limited time, no strings attached.

“What we’ve learned is it works,” said Dionne Bussey Reeder, executive director of the non-profit Far Southeast Family Strengthening Collaborative.

Hers is one of four non-profits in a $4.2 million program that launched last summer in Anacostia, a mostly Black community that has missed out on a flood of investment over the past decade that transformed much of the city.

The work – called THRIVE East of the River – was jumpstarted by the pandemic and is now part of a nationwide wave of pilot projects aiming to keep people afloat through the COVID-19 crisis and propel recovery thereafter.

Under the initiative, 500 low-income Anacostia families get $5,500, either as a lump sum or in monthly instalments, as well as groceries and other supplies free for five months.

The philanthropic program is likely “the largest payment of short-term private emergency cash relief ever offered” in the United States, according to the Urban Institute think tank.

Direct financial assistance is the “missing link” that goes beyond standard programs such as housing or education, Bussey Reeder said, adding: “The pandemic gave us the leverage to move it forward quickly.”

Organizers hope the pilot leads to a model that can be replicated in cities across the country.

PARTY TRICKS

When Jamesa Lewis was accepted into the program in March, she could not believe her luck.

A mother of three, 31-year-old Lewis had not earned since the birth of her daughter, now 4, but had attended classes in preparation to resume work – then the pandemic hit.

So she shifted gears and began making accessories for girls’ birthday parties. Business took off, but was hobbled by her dependence on public transport.

Now she plans to use the THRIVE assistance to buy a car.

“The car will help so much,” she said. “Now if I have one child here and another there and orders to complete, we can get it all done and keep the money flowing.”

Yet critics like Angela Rachidi, a scholar with the American Enterprise Institute think tank, warn against potential negative impacts of long-term cash assistance, such as reducing employment as people substitute government payments for work.

Over time, she said, “reduced employment can harm individuals if their income is less than it would otherwise be without employment and harm communities when an increasing share of people do not work.”

Still Rachidi, who previously oversaw New York City’s Department of Social Services’ policy research and program evaluation efforts, likes that new interest in these programs is taking place particularly at the local rather than federal level.

She hopes that “local organizations and philanthropy will study these programs … and assess the costs and the benefits.”

The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development declined to comment.

LONG-TERM STABILITY

Debates over cash-based programs such as THRIVE have been brewing for decades, said Mary Bogle, a principal research associate with the Urban Institute, with some federal usage until the 1970s.

Nordic countries are big fans, she said, while the U.S. state of Alaska has long run a cash transfer program.

Cash assistance became increasingly politicized in the United States, seen by some as handouts that would breed laziness, but data suggests otherwise, Bogle said.

“For all kinds of reasons, it’s one of the more equitable solutions we can come up with,” said Bogle, who is part of formal monitoring of the THRIVE program.

“It gives people a choice,” she said, noting that recipients often spend the money more wisely than they would under the rules of a more traditional assistance program.

Early anecdotal findings on THRIVE are also encouraging on the social impact, be it more family time or less parental stress.

Bogle points to recipients, like Lewis, who use the money to kickstart home-based ventures, saying: “They couldn’t get the cash they needed any other way.

“And they’re saying that rather than spend it on anything short term, they’re going to see whether they can spend it on something to stabilize and get out of poverty in the long run.”

GUARANTEED INCOME

Because THRIVE specifically targets a community that has traditionally missed out on investment, experts say it also addresses the racial wealth gap.

But in the United States, the pandemic has also supercharged a much broader national discussion about cash assistance, including guaranteed or universal basic incomes.

The idea rose to new prominence last year as a focus of presidential candidate Andrew Yang, now a candidate for mayor of New York City, who proposed giving $1,000 a month to every U.S. adult.

The idea is “proliferating wildly”, said Natalie Foster, co-chair of the Economic Security Project, a nonprofit that backs the handouts. “This is a moment for cash transfer.”

Polling from the Pew Research Center shows that eight in 10 Americans back at least two rounds of coronavirus payments.

The Appeal and Data for Progress, both think tanks, also found solid support among voters for cash programs of $500-$1,000 a month.

Foster has been part of the first mayor-led pilot project on guaranteed income, in Stockton, California, which gave $500 a month to 125 low-income residents from 2019 until last year.

During the first year, full-time employment went from 28% to 40%, while recipients reported being happier and healthier, according to a preliminary study released last month.

Other programs have followed in multiple cities, several using federal pandemic stimulus money, Foster said.

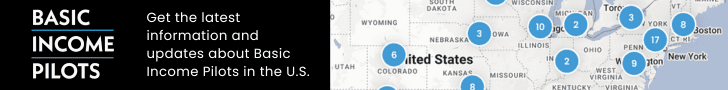

Saadia McConville – of the Mayors for a Guaranteed Income network – said her group started last year with 11 members and has since grown to 40; at least nine programs are currently underway, with six more in the pipeline, she said.

While cities are at the forefront, Foster expressed hope that the pandemic has spurred the federal government to catch up.

“So much of what we’re seeing today with forward-thinking community organizations like THRIVE are guaranteed-income demonstrations that hopefully will inform the federal income guarantee in America.”