Guest Editorial by Almaz Zelleke, Associate Professor of Practice in Political Science, NYU Shanghai

Fifty years ago, on August 8th, 1969, President Nixon proposed a new anti-poverty plan in an address to the nation. The Family Assistance Plan (FAP) would provide families with an annual guaranteed minimum income (GMI) of $500 for each adult and $300 for each child. Unlike “welfare” the GMI would go to all, ending the distinction between the working and non-working poor that had bedeviled previous attempts to alleviate poverty.

The introduction of a surprisingly liberal policy by a Republican administration was spurred in part by the end of a multi-year investigation of poverty commissioned by President Johnson. The bipartisan commission’s report, Poverty Amid Plenty, documented the futility of expecting jobs to lift all Americans out of poverty. Steady jobs were simply unavailable in some areas of the country, and paid too little to provide a decent standard of living in many others. Targeted relief to the unemployed could address the first problem, but not the second. But any benefit level high enough to afford a decent standard of living to the unemployed poor would likely pay more than the jobs that might become available, creating a “poverty trap” of a life on welfare with no opportunity to achieve higher earnings, or a life of poverty-level wages with no access to welfare. Furthermore, since the nation’s largest welfare program, Aid to Families with Dependent Children (AFDC), only benefited families without a potential breadwinner present, welfare policy seemed to encourage low-earning men to desert their families.

Nixon’s proposed solution to these structural dilemmas was to make the same benefits available to the working and non-working poor, and to allow those benefits to phase out slowly as earned income rose, rather than ending all at once when any wages were earned.

FAP would act as a cushion against low or intermittent wages–for those whose only employment option was seasonal agricultural work, for example–and would phase out once annual income rose to a level high enough to meet a family’s needs. Benefits would go to both single parents and married couples, bolstering family stability amid the changing social norms of the 1960s.

FAP faced resistance from those who thought any welfare benefits would discourage the poor from trying to find work, but the President promised that adult FAP recipients would have to work if jobs were available, unless they were mothers with small children at home. Nixon believed he could build support for the bill because FAP had something for everyone, regardless of party or regional affiliation: FAP would alleviate poverty, incentivize work, uphold traditional family values, relieve Northern cities from the burdens of growing welfare rolls, and send a much-needed financial stimulus to the poorest regions of the US, including Appalachia and the South, which had been left behind in the country’s post-war economic boom.

Had FAP been signed into law, its positive effects would have been evident within a year. The ability to combine FAP and wages would have reduced the number of families living in poverty to historic lows and increased labor force participation, since accepting even part-time, low-wage work would have made families better off. Child poverty would have been virtually eliminated. FAP would have raised living standards in the South and boosted its economy in response to increased consumer spending and local investment power. The shift to a federally-funded FAP from the federal-state partnership of AFDC would have led to overall cost savings for the states because it eliminated much of the administrative cost of monitoring eligibility for welfare: FAP benefits were to be distributed by the Social Security Administration, and any necessary adjustments based on earnings were to be made through the IRS during tax filing at the end of the year. The portability of FAP as a federal benefit would have enabled families to move to where higher paying jobs were located, and helped finance the higher education and training levels many jobs increasingly required.

FAP’s success would have come at a cost, of course, more than doubling the federal government’s annual spending on AFDC, but the necessary tax increases would have come just at the time, in the early 1970s, when GDP growth was beginning to be captured by the very wealthy rather than shared among all Americans. Taxation of the wealthy to fund and eventually expand FAP would have helped the US avoid the steep increases in inequality we began to experience at the end of the 20th century and which continue today.

None of this actually happened, of course, because FAP never became law. The poverty rate is the same as it was when President Nixon proposed FAP, and participation in the labor force by working-aged Americans is declining and projected to return to rates not seen since the 1960s, when most women did not work outside the home. Child poverty is actually higher now than it was in 1969, and the US has infant mortality and maternal death rates higher than any advanced economy and many current and former communist regimes. Welfare programs–those that remain after a supposedly liberal President Clinton ended AFDC in the 1990s–are still administered by intrusive and costly state bureaucracies. Income tax rates are lower, and income and wealth inequality much higher than during the Nixon administration.

What happened to FAP? FAP’s demise is often attributed to racism and misogyny: whites wanted an end to welfare, which they believed was going overwhelmingly to blacks, and AFDC’s restriction to families without a breadwinner further narrowed its perceived beneficiaries to black women. Others attribute FAP’s defeat to Americans’ cultural resistance to erasing the distinction between the “deserving” (working) poor and the “undeserving” (work- and family responsibility-avoiding) poor.

But FAP wasn’t killed by voters. Nixon easily won re-election after he proposed two versions of the bill during his first term. And it wasn’t killed by the House–the chamber most directly influenced by voter opinions. Both versions of FAP cleared the House Ways and Means Committee and passed the House with bipartisan support in 1970 and 1971. FAP was killed by the Senate–stalled by the Senate Finance Committee and ultimately doomed by opposition from its members. Democratic Louisiana Senator Russell Long, chair of the Senate Finance Committee at the time, was vehemently opposed to FAP, but he was not alone. The ranking Republican on the committee, Delaware Senator John Williams, opposed FAP from the start and badgered the Nixon administration to make changes to the bill that he knew would increase its cost beyond what even the administration was prepared to defend. Democratic New York Senator Abraham Ribicoff also opposed the initial bill because he wanted the benefit level–only two-thirds of the federal poverty threshold and less than AFDC payments in New York at the time–to be raised.

Long’s opposition to FAP is the most interesting, not only because of the power he wielded as the committee chair, or because he might have been expected to support it as the son of populist Huey P. Long, who championed a much more generously redistributive program called “Share Our Wealth” in the 1930s. Long’s opposition is the most interesting because its effects extended fifty years into the future. Long was not only able to keep the FAP bills from passing, he skillfully used the Congressional struggle over FAP to enact his own version of welfare reform with a very different approach to the poor, with lasting effects that continue to shape US poverty programs today.

Long is characterized by his biographers as liberal on tax and spending issues and conservative on social issues–mostly on civil rights legislation and maintaining the segregated “Southern way of life.” He was not opposed to redistribution in general, voting for minimum wage and Social Security increases, supporting the creation of Medicaid and Medicare, and working to eliminate some tax benefits for the wealthy over the course of his career. Unlike many of his fellow Southern senators, Long had supported President Johnson’s anti-poverty programs, including the creation of the Job Corps, Volunteers in Service to America, and loans for businesses that hired unemployed workers. He would later support President Nixon’s establishment of safety standards in workplaces through the Occupational Safety and Health Act (OSHA), and the Finance Committee under his leadership would propose adding deductions for businesses that hired welfare recipients to Nixon’s 1970 tax reform proposal. Long is best known as the driving force behind the Earned Income Tax Credit (EITC), Employee Stock Ownership Programs (ESOPs), and Supplemental Security Income (SSI) for seniors whose Social Security payments do not provide an adequate income–all programs designed to promote the economic interests of the poor and working class.

At the heart of Long’s opposition to FAP was not its redistribution of federal funds to the poor, it was its empowerment of the poor without regard to whether they worked or not. Despite Nixon’s promise of work requirements, at least for able-bodied male recipients, Long correctly intuited that FAP’s GMI would allow poor men to be a little more selective about the jobs they took and would allow poor mothers to exempt themselves from the workforce altogether–at least in the South, where FAP benefits would go further than they would in the north. Vividly illustrating this concern, a New York Times article written after FAP’s final defeat quotes Long as having exclaimed to HEW Secretary Elliot Richardson during deliberations over the bills “I can’t get anybody to iron my shirts!” To ensure a reliable workforce for low-paying, dead-end jobs even he recognized as unappealing, Long preferred workfare or wage subsidies–benefits conditioned on proof of employment–rather than a floor of unconditional economic security.

As with much of the opposition to FAP, Long’s motivations are often assumed to be racially grounded, and there is abundant support for that view in his many statements about how African-Americans would only improve their lot if they became more like whites in taking personal responsibility, striving for economic independence, and earning through hard work the same jobs as whites. But FAP wasn’t directed at African-Americans. It was specifically designed by the Nixon administration to help white low-income workers who were excluded from welfare programs, and especially those in the South, where almost half of poor Americans lived at the time, most of them white.

Tempting as it is to consider Long’s opposition to FAP as part of his segregationist civil rights position, doing so ascribes too narrow a meaning to his explicit desire to preserve the “Southern way of life.” The Southern way of life included class and gender stratifications as well as the obvious racial stratification. The South has always had lower wages and fewer worker protections–beginning with none for slaves, of course–than other regions in the US. Racism and segregation served not only to keep African-Americans economically dependent, it also reinforced divisions between working-class whites and their natural economic allies in fighting for higher wages and better working conditions. From this perspective, the Nixon administration’s strategic error was not in erasing the distinction between the working and non-working poor, but in assuming that funds sent to Southern workers would be welcomed by Southern elites whose own fortunes and lifestyles depended on the steady availability of disempowered workers–black and white–for their farms, textile mills, laundries, and domestic work.

All of Long’s efforts on behalf of the working-aged poor were in the form of wage subsidies, employment enhancements, and workfare programs, rather than in measures that would improve, even slightly, the bargaining power of workers against employers. The EITC, proposed by Long during the FAP debate and enacted three years later, has entrenched two ideological and demonstrably false claims in our contemporary poverty programs: that jobs are the road to economic advancement for the poor, and that the poor need the discipline of enforced work requirements to make them work at all.

Distinguishing a GMI, like FAP, and a wage subsidy like the EITC may seem like splitting hairs, but it goes a long way toward explaining why half a century and billions of dollars after the federal government first undertook policies designed to alleviate poverty it remains as entrenched in American society as it was in Nixon’s day. Income support can be targeted to the needy in a number of ways. It can be structured as a flat grant, like FAP or AFDC, that is provided in full when earned income is 0 and then is taxed away as earned income rises or, like the EITC, as a wage subsidy that only begins once earnings rise above 0, increases in size as earnings increase to a specified amount, and then is taxed away as earnings rise above that amount. In either case, the subsidy can be additive, meaning that multiple eligible recipients can keep their full individual subsidies when they join together in marriage or household, or scaled to household size, with smaller incremental benefits for additional family or household members. A flat, additive grant is a more generous and transformative form of income support than a scaled wage subsidy.

While AFDC was a scaled flat grant, FAP would have been an additive flat grant; the EITC is a scaled wage subsidy. FAP’s primary improvement over AFDC was that it could be combined with earned income, rather than lost as soon as a recipient took even a low-paying job. Even more importantly, FAP included an independent child benefit that would not have been forfeited even if the father and mother–who in the second version of the bill was no longer exempted from work requirements–failed to maintain eligibility for their benefits; neither AFDC nor the EITC included an independent child benefit. Most significantly, FAP would have provided a full benefit for those without jobs as long as the adults were willing to work, and would have provided a relatively large supplement to low-wage workers or those with only the possibility of intermittent work; the EITC pays its largest benefits to full-time workers, and nothing to those without jobs. FAP, with the most generous supplement going to the poorest–whether they had earned income or not–would have had a larger effect on alleviating poverty than the EITC, which gives its largest benefits to workers higher up the income scale.

Of course, the upfront cost of FAP would have been much higher than the cost of the EITC. But that calculation takes account only of the initial outlay, not of the potential gains generated by the economic stimulus to poor communities, taxes from benefit recipients no longer prohibited from working, the increased productivity of a more secure, better trained and educated workforce, or the economic efficiencies induced by industries forced to modernize in the face of higher costs for low-skilled labor.

Had Russell Long raised himself up to his elite position by dint of hard work and sacrifice, his view of work as the road to economic security for the poor might carry weight. But that wasn’t his story. Long’s status as the son of Huey Long, and the nephew of Earl Long, Governor of Louisiana after his brother’s assassination, paved the way for his election to the US Senate at age 30 after nothing more than a local law practice and a year in his uncle’s administration. His father’s machine politics and crony capitalism–the corrupt side of his populist economic views–resulted in Russell Long owning shares worth millions of dollars in an oil company his father co-founded with insider knowledge and appropriation of state resources. Long was able to use the Finance Committee’s oversight of federal taxes to grant favorable tax status to the oil and gas industry, to the benefit of his own family and other industry insiders, for decades. In 1976, Long’s wealth was estimated to be over $100 million–not bad for someone with a Senate salary of less than $50,000 at the time. At the end of his career Long told a reporter he considered FAP’s defeat the most rewarding victory of his four decades in the Senate.

FAP wasn’t perfect, and its conditionality would have excluded those deemed to be avoiding work, rather than unable to find it. President Johnson’s commission had recommended an unconditional GMI–what we now call a basic income–in its report, precisely to avoid having any of the poor fall through the cracks of conditional programs. But FAP would have been the first step toward a more effective poverty alleviation strategy. A benefit that went to both the working and non-working poor could have created a large constituency for its expansion, and could have empowered the poor to agitate for a greater redistribution of income and wealth through other means. Long’s defeat of FAP has left the EITC as our main poverty alleviation program–a program that subsidizes the payroll of low-wage employers and does nothing to empower workers to fight for higher wages or better working conditions, because employers know they need their jobs to qualify for the benefit. Our stagnant poverty numbers, worsening wellbeing statistics, and politically powerless poor are the lasting legacy of Long’s defeat of FAP.

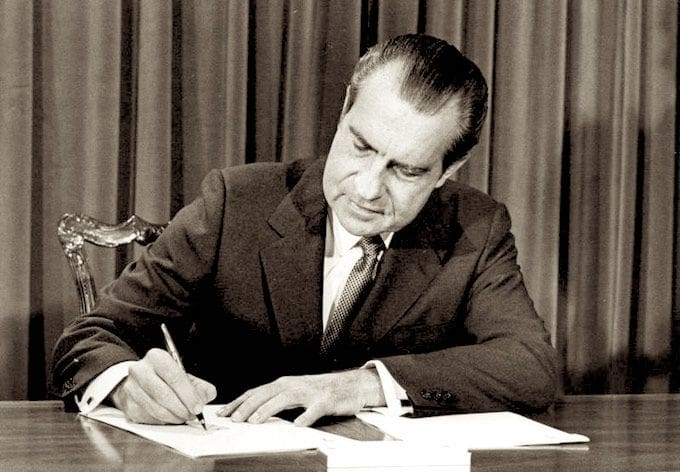

WATCH THE VIDEO:

President Nixon Unveils the Family Assistance Program On August 8, 1969, President Nixon addressed the nation on his administration’s domestic program proposals.