Cutting off unemployment insurance early is all politics, not economics. This is why UBI is so critical.

By: Emily Stewart

Karen just needs a few more months to finally get her massage business back off the ground. Business was booming before the pandemic, and relying on unemployment insurance hasn’t been easy. “I’ve been saving every penny,” she tells me, describing, with what sounds like a hint of shame, how she’s “learned to live without lights” to try to keep her electricity bill low and has started to shower less to cut down on the water. “I made a lot more money when I was working,” she says.

It’s taking her some time to get clients to return, and she expected to be back to work and off unemployment insurance by August. But the rug is being pulled out from under her: Texas Gov. Greg Abbott (R) has decided to opt his state out of expanded unemployment benefits early. And he’s hardly alone in that choice.

Federal unemployment programs that added extra weekly money and extended benefits to those who wouldn’t normally receive them, such as freelancers and people who have been unemployed long-term, were put in place in response to the pandemic. They were supposed to end on Labor Day. Now 25 states — all Republican-led — are cutting them off as early as this week, arguing that the extra support is no longer needed.

They say that generous benefits are keeping people out of work and causing a labor shortage, even though it’s far from clear that’s what’s going on.

States are about to undertake a reckless and unnecessary experiment in cutting off expanded unemployment in the midst of a rocky recovery, with the lives and livelihoods of an estimated 4 million workers in the balance.

“We’ve had this message throughout the pandemic that we’re going to make sure that people who were disadvantaged by it would have the support they needed until things recover,” said Andrew Stettner, senior fellow at the Century Foundation. But from some corners, that message has gone away. “Sympathy for the unemployed disappeared the minute some people got two vaccine doses.”

Many workers, including Karen (whose last name is being withheld to protect her privacy), have been caught by surprise and are scrambling to figure out what’s next. “I don’t know how I’m going to be able to make my rent,” Karen says. “I’m going to have to start begging clients to come in.”

Cutting off unemployment early is a political decision, not an economic one

When the Covid-19 pandemic took hold in 2020, millions of people lost their jobs seemingly overnight, and Congress took sweeping measures to try to provide them with extra support. The federal government added an extra $600 in weekly federal benefits through July 2020. (Those dollars expired for a while but were then reinstated as $300 in extra benefits.) It also enacted programs that would support people who don’t normally qualify for unemployment, such as freelancers, independent contractors, and gig workers, and for people who are long-term unemployed. They also lengthened the number of weeks an unemployed worker could receive benefits once they exhausted their state benefits in an effort to help the long-term unemployed.

That decision — namely, the extra dollars in federal benefits — was politicized from the start. Many Republicans and even some Democrats argued that $600 was just too much, noting that some people would make more on unemployment than they would at work.

They also fretted that overly generous unemployment would keep people from returning to work, a perennial talking point among businesses and conservatives. “The extra money was very politicized, even more politicized than other unemployment insurance issues in the past,” Stettner said.

As vaccines have become more widespread and the economy has started to recover, the fretting around unemployment insurance has reached a fever pitch amid chatter that there’s a labor shortage and speculation about what’s causing it. There’s a simple, capitalistic answer if companies are struggling to find workers willing to work at the wages and conditions they’re offering: raise those wages, and make the conditions more attractive to workers. But the chatter continued, and the April jobs report, which showed far fewer jobs were added to the economy than expected, became the tipping point. Business groups, including the Chamber of Commerce, upped calls for states to end unemployment.

Montana and South Carolina said they were going to opt out of enhanced unemployment programs, and now half of all states, all Republican-run, have followed suit. All are axing the extra $300, and most are getting rid of the other expanded programs. May’s jobs report didn’t provide much clarity on the situation: The US economy added 559,000 jobs last month, a number that was neither terrible nor stellar.

“Sympathy for the unemployed disappeared the minute some people got two vaccine doses.”

Those in support of cutting off jobless benefits early say that it’s an economic decision. But it’s hard not to see it as one largely driven by politics.

About 8 million fewer people are currently employed than prior to the pandemic, and people ages 20 to 24 continue to see double-digit unemployment rates. While vaccine rates are rising and businesses are reopening, the economy is going through many fits and starts, and the recovery is going to take time. Nearly 16 million people are still receiving benefits under all unemployment programs, which, as the Associated Press points out, is about eight times as many people as were getting benefits in August 2014, when the unemployment rate was about what it is now. Rep. Don Beyer (D-VA), chair of the US Congress Joint Economic Committee, released a report that found cutting off unemployment early could cost local economies over $12 billion, and just ending the $300 will cost would-be beneficiaries $775 million each week.

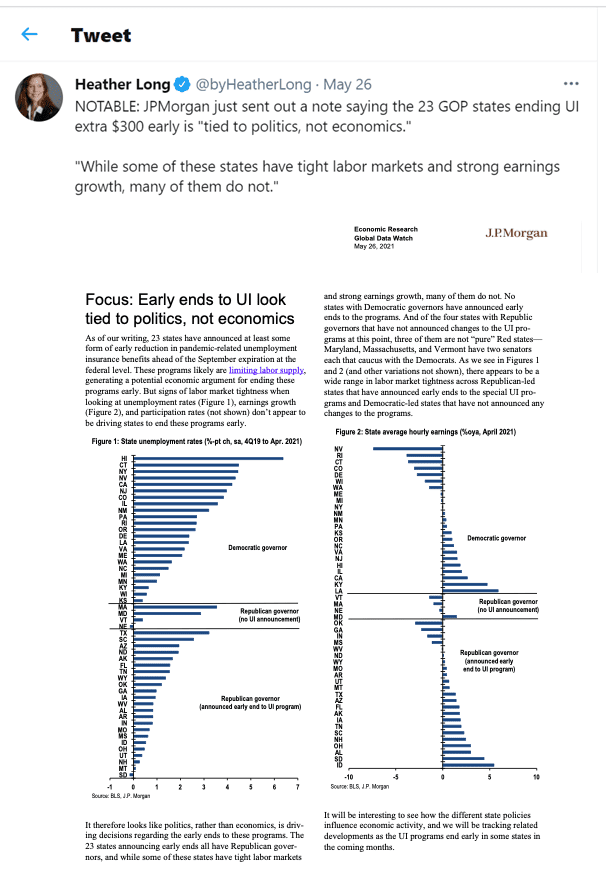

JPMorgan’s economic research team wrote in a note in late May that opting out of UI before the timeline set by Congress appears to be “tied to politics, not economics.” They noted that indicators of economic health didn’t really coincide with unemployment-related decisions. “While some of these states have tight labor markets and strong earnings growth, many of them do not,” they wrote.

The unemployment rate in Texas, for example, is still above the national unemployment rate. And many people looking for work there know just how hard it can be. Lynn, who lost her job as an office manager near Houston in March, has sent out over 100 résumés but so far has only gotten two callbacks.

“There isn’t anything I haven’t tried to get a job over the last two months,” says Lynn, whose last name is being withheld to protect her privacy. “Do you think I like sitting on my tookie all day?”

At her age — she’s 59 — she worries a lot of companies just aren’t interested. But she’s really not in a position where she can take just anything: She needs to make enough money to pay for her mortgage so she can keep her home. Her partner uses a motorized wheelchair, and they can’t easily pick up and move. She’s already strategizing how she can make extra money while she continues to look for steady work, by mowing lawns and cleaning houses. “We’re going to be so screwed,” she says. “There’s going to be a lot of sleepless nights here.”

Karen told a similar story of anxiety over Abbott’s decision. “I’ve had nightmares for two weeks since this has been announced,” she said. Her dog is on anti-anxiety medication, and she said she’s snuck one sometimes just to sleep.

It’s not clear what this will prove, or whether proving anything is worth it

There’s been quite a fierce debate about what is contributing to some workers feeling hesitant to go back to work and how quick or slow the labor market recovery will be. While some business groups and economists point to unemployment insurance as the culprit, there are also plenty of other explanations — continued concerns about the pandemic, a lack of access to child care, people rethinking their career paths or holding out for better jobs. It’s difficult, if not impossible, to figure out exactly what is motivating who, and many people could be motivated by multiple factors.

A working paper out of the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco estimated that the $300 weekly unemployment supplement has been making a “small but likely noticeable contribution to job-finding rates and employers’ perceptions of worker availability.” How small: They estimate that if seven of 28 workers receive job offers they would normally accept in the early months of this year, just one would say no in order to hold on to the $300.

The question then becomes: Does the choice made by that one worker to stay unemployed a little longer really need to outweigh the lifeline that many workers desperately need?

“If you’re saying I’m just going to shut off your benefits, but I still don’t have child care, and I still don’t have a way to ensure my child is attending their digital school, how is that going to force me into the labor market?” said Rebecca Dixon, executive director of the National Employment Law Project (NELP). “It may force me into homelessness. It may force me to be hungry. There’s an enormous amount of workers that are still behind on rent. This whole narrative is just completely wrong, and it’s incomplete.”

She also nodded to the racial undertones of what’s happening with unemployment: Many of the states cutting off pandemic programs early are those with many Black workers, and they’re also often the states with the stingiest and hardest-to-navigate unemployment systems. “At the root of all this is this narrative that Americans have to be forced to go to work, and it is completely and totally rooted in structural racism,” Dixon said. “Because who was being forced to work in the 1800s? Black people.”

The point of unemployment isn’t to make workers take just any job. It’s designed to give workers the time to match with a job that’s at least on par with the job they had before, which is what many of them are doing.

Justin, who runs an electric taxi operation in downtown Austin, didn’t want or need to find another line of work during the pandemic. He took out two Paycheck Protection Program loans for small businesses and took advantage of unemployment. Now that nightlife is picking back up and people are out and about, he’s headed back to work and off of jobless benefits. For him, the system worked. “Not having a job wasn’t my issue; it was not being able to work,” he said.

“If you’re saying I’m just going to shut off your benefits, but i still don’t have child care, and I still don’t have a way to ensure my child is attending their digital school, how is that going to force me into the labor market?”

The hope that governors and businesses have in cutting off unemployment is that it will force people back into the workforce and make it so that they have basically no option but to accept any job, no matter the pay or benefits or hours. It’s not clear how their experiment will work: Indeed found that job search activity rose modestly — and temporarily — when states announced they were opting out early.

Telling people they would have support through the summer and then unexpectedly taking it away doesn’t solve the problems that might be keeping them out of work; it just turns those problems into an emergency.

Unemployment insurance needs an overhaul

Once governors began announcing they were cutting off unemployment insurance, many people were shocked. Congress had said unemployment would go through Labor Day, and workers were caught off guard that this could even happen. After all, the programs being cut off are funded by federal money, not the states.

“These are temporary programs, and the way that these temporary programs are administered is an agreement between the secretary of labor and the governor of the states, and that agreement gives either side — the Labor Department or the state — 30 days to terminate it,” Stettner said. “That’s what’s happening. They’re exercising this termination clause in the agreement.”

Some experts, politicians, and advocacy groups have argued that the Labor Department should step in to try to stop states from ending benefits. NELP put out a memo laying out the case that the labor secretary has to figure out a way to keep Pandemic Unemployment Assistance (PUA), which covers self-employed people, part-time workers, and people who wouldn’t otherwise qualify for regular unemployment compensation, going. Sen. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) sent a letter to Labor Secretary Marty Walsh reiterating NELP’s case.

Thus far, the administration insists that its hands are tied on keeping unemployment going in states that are trying to shut it off. A Labor official told Vox that they believe their authority is nil on the matter, and that because states administer unemployment insurance, it’s next to impossible to find workarounds where the federal government or other states would pay benefits. The official said they are still open to ideas.

Some advocates and workers have expressed doubts that there’s really nothing the federal government can do, as well as frustration that many Democrats aren’t speaking out more about the matter. “I have been extremely disappointed by the silence from President Biden and from the secretary [of labor] to not sort of more publicly call out [what’s happening],” said Rachel Deutsch, who heads the Unemployed Action movement at the Center for Popular Democracy.

The White House hasn’t exactly offered a full-throated defense of expanded unemployment.

At a briefing on Friday, White House press secretary Jen Psaki said governors “have every right” to opt out of unemployment benefits and emphasized that no one in the administration “has ever proposed making these permanent or doing it over the long term.” She said that deciphering the extent to which expanded unemployment is keeping people out of work is “difficult to analyze.”

Telling people they would have support through the summer and then unexpectedly taking it away doesn’t solve the problems that might be keeping them out of work; it just turns those problems into an emergency.

Some unemployed workers are organizing to try to protest and keep their promised benefits, and advocates insist there are ways to help. But the current situation points to the broader problem of how deeply flawed America’s unemployment insurance system is. If it were more robust, we wouldn’t be here. “This is actually a microcosm of the full dysfunctionality of the unemployment insurance system as a whole,” Deutsch said.

This has been painfully evident for a long time, and particularly acute during the pandemic. Unemployment insurance is run as a state-federal partnership that gives states a lot of leeway in how they administer the program. That has translated to low benefits in many states and impossible-to-navigate bureaucracy. Even more than a year after the pandemic hit, workers still describe spending hours on the phone and on websites trying to figure out how to apply for unemployment. Ken, a Texas teacher who is trying to figure out what to do without unemployment for the last two months before he goes back to school in the fall, said Sen. Ted Cruz’s (R-TX) office finally helped him get through to the state agency to at least collect what he’s owed before he’s cut off. “If I send a message to Ted Cruz’s office, they get me on a call list, and I get a call back,” said Ken, whose last name is being withheld to protect his privacy. (Anecdotal evidence from a Facebook group of unemployed people from Texas suggests Cruz’s office is highly effective in helping people navigate the system.)

What happens consistently in downturns is that federal lawmakers need to step in to decide whether to help unemployed people instead of putting in some sort of automatic triggers, which would mean help is dictated by economic conditions and not political whims. Maybe some of the states cutting off benefits right now do have economies that merit it, but not all of them do.

“We have to have standards for the benefits at all times so we don’t have to so drastically increase them,” Stettner said. “And if we’re going to have federally supported programs, we may need to have some provision in law that allows the federal government to directly pay them if the state refuses.”

We don’t know when the next recession will come, but we know that it will. And the country and workers will be stuck in this doom loop unless there is real change or, perhaps, the entire system is overhauled.

“Fundamentally, if we are really serious about having an income support program that is countercyclical, that actually puts money into the economy when we’re heading into a downturn and provides people with money to meet their basic needs, we actually need to create that program,” Dixon said, “because what we have now is not adequate.”

Karen, whose husband died in 2017, is currently collecting about $418 a week in unemployment. It’s enough to pay the rent for her house and for the shared office she’ll soon be working out of yet again, but not much more. “It’s just enough to make it by,” she said, “and live in the dark.”

Later this month, she thinks it will be cut to $0.

_________________________________________

Original article appeared in Vox: https://www.vox.com/platform/amp/policy-and-politics/2021/6/3/22465160/states-ending-unemployment-labor-shortage-texas