“Work is the best remedy for any shock,” wrote Arthur C. Clarke in his classic novel, 2001: A Space Odyssey. Today, we’re living in a culture of shock. We have been shocked out of our curated lifestyle bubbles as we collectively witness a terrifying rise of extreme right-wing rhetoric and a massive upheaval in global political systems. Work provides not only a distraction, but a means of survival. Finding work though, isn’t guaranteed. To those who are paying attention, there’s a lot to be alarmed about. Between immense economic inequality and the automation of thousands of jobs, economists are warning that millennials are at risk of becoming a lost generation.

“Every generation expands its definition of equality,” said Mark Zuckerberg in his Harvard commencement speech to the graduating class of 2017 back in May, “and now it’s time for our generation to define a new social contract.” The challenge for millennials, he stated, “is to create a world where everyone has a sense of purpose.” Purpose, for most of this generation, stems largely from work—it’s part of your “personal brand.” But very few people get the chance to pursue their dreams, and even if you do achieve professional success, are you truly free to live your life?

One route to economic equality is universal basic income, or UBI, a concept that can be traced back as far as the 13th century according to Guy Standing, co-founder of the Basic Income Earth Network, and Professor of development studies at the School of Oriental and African Studies in London. It’s a form of government social security that guarantees all citizens a basic and unconditional sum of money every month in addition to other earned income. International beta tests—past and ongoing—from India to Canada, show the promise of UBI, with co-signs from Elon Musk to Bill Gates. “We should explore ideas like UBI,” said Zuckerberg in his Harvard speech, “to make sure that everyone has a cushion to try new ideas.”

At present, UBI is being explored as a potential way to alleviate the forecasted wave of mass unemployment due to automation. Experts are warning of a post-work future, one that’s already become a reality for many people with routine manual jobs. Nobody is safe from this type of disruptive innovation; robots are learning how to think which means non-routine cognitive work is at risk too. UBI could provide a safety net against this type of displacement.

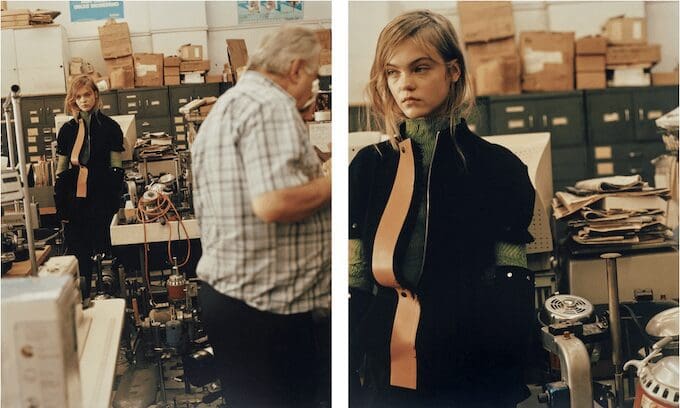

Most of the styles of clothing we wear are birthed from working class necessity. Today, the utilitarian aspects of denim and canvas are considered attractive for aesthetics rather than function. In a post-work future where manual labor is lost, what kind of twisted workwear will we come up with? Craig Green is already designing workwear-inspired garments that could become the uniform for a disillusioned workforce yearning for the return of real craftsmanship. As we invent new automated industries, maybe we’ll turn to tech-wear instead, for a new, maximum utility. In a post-apocalyptic state of mind, gear that’s made for AI industries could be the perfect fit. “When you don’t have Obamacare, dress up in tech-wear,” reads the Hypebeast comment section.

In a bout of nostalgic futurism, maybe we’ll turn to a Victorian redux, the puffed sleeves of a Loewe jacket resembling these silhouettes. With immense class divides, mutated 18th century aristocratic aesthetics could provide the uniform for unemployed millennials and an elite, thriving upper class.

Should we be skeptical of messages about economic inequality coming from billionaires, though? Many of the most vocal proponents for UBI are the very ones creating the technology that’s displacing jobs. Enabling increased entrepreneurship seems to be their focus, rather than solving the root issues that cause economic inequality in the first place. Technological revolutions have always come with growing pains, one could argue that automation will create new jobs in place of outdated ones. One thing here is likely: regardless of technological advances, workers will continue to put in the same hours with the same pay. The rhetoric that increased entrepreneurship equals a utopian society is one-sided. What about equality as a means for liberation from these systemic ideals?

“UBI is voluntary participation capitalism. What we have now is mandatory participation capitalism. I believe this model of mandatory participation capitalism is an affront to a free society,” says Karl Widerquist, Associate Professor of political philosophy at SFS-Qatar at Georgetown University and author of Independence, Propertylessness, and Basic Income: A Theory of Freedom as the Power to Say No. “Capitalism is based on people who own all the resources, and other people who can only use those resources if they take a subordinate position. Most of us will have no choice but to participate in the capitalist system, not as a capitalist, but as a worker for years. Basic income gives you the power to say no to that. To say, ‘I work because I want to, not because you threaten me with homelessness and starvation.’

“The potential for robotics to give us more leisure is incredible if we’re allowed to take it. But most of us can’t demand that. If we don’t work 40 hours a week, 50 weeks a year, we don’t have any income,” says Widerquist. “We should all receive some of the benefits of automation. If you’ve had a job anytime in the last 40 years, you’ve done something to further the great economic growth we’ve had.”

Chronic economic insecurity is toxic and a sense of freedom doesn’t come from an Instagram feed filled with pictures of nature. Nor does it come from endlessly climbing the corporate ladder. The scarcity mindset that is perpetuated by the lack of proper compensation and workers’ rights only worsens mental health issues, making for an increasingly volatile social and political climate. History proves that the only way to change things is to mobilize. “Remember the 1% is only 1% of the people,” says Widerquist. “We have the other 99%.”

Romany Williams is a stylist and associate editor at SSENSE.

Text: Romany Williams

Photography: Étienne Saint-Denis

Photography Assistant: Melissa Gamache

Styling: Romany Williams

Hair and Makeup: Ashley Diabo / Teamm Management

Model: Daria / Folio, Daynis / Another Species

Production: Jezebel Leblanc-Thouin

Production Assistant: Erika Robichaud-Martel