Stimulus Checks Just Enough To Plug A Few Financial Holes Right Now

The federal government sent out checks for families under the CARES Act since March. People could get up to $1,200 plus an additional $500 for each child in their household. The amount of those payments declined and eventually fell to zero at higher incomes. Congress intended these payments to help struggling families navigate the uncertain waters of the ongoing recession. Policymakers and economists understood that families would use the money to help them pay their bills right now and over the coming weeks and months. But the latest data show that the checks were not enough to boost people’s financially security for very long, especially not among African-American and Latinx families.

Most people received some money from the stimulus checks, according to the latest Census data. In early June, 85.5% of people said that they had already received their stimulus payments. And the shares of households receiving stimulus payments decline with higher incomes. For instance, 87.6% of households with incomes below $25,000 got a stimulus check, while only 51.1% of households with incomes above $200,000 did. The stimulus payments largely went to those who needed the money the most.

There are also some key differences in receipt of the stimulus checks by race and ethnicity. A high of 90.2% of African-Americans said that they got a check and still 80.5% of Asians said they did, the lowest share of any population group by race or ethnicity. In comparison, 85.4% of whites, 83.2% of Latinx and 87.9% of those self-identifying as other races, mainly Native American, Alaska Natives and Pacific Islanders, as well as those identifying as multiple races said that they had received a check. More than four-in-five people in each group got some money from the stimulus payments, highlighting the widespread impact of income support in the deepest recession since the Great Depression.

People generally use the money to pay everyday expenses. More than two-thirds of all people, 70.1%, said that they already used or plan on using their stimulus money to pay for things like groceries, utilities and personal care.

The share of people who used the extra money for such expenses declines with income. The overwhelming majority, 87.6%, of households with incomes below $25,000 spent their money on everyday expenses. But only 51.1% of households with incomes above $200,000 did. About half of all higher income households clearly have some room to put part of their stimulus money away for a rainy day, which may come sooner than expected, given the depths of the recession.

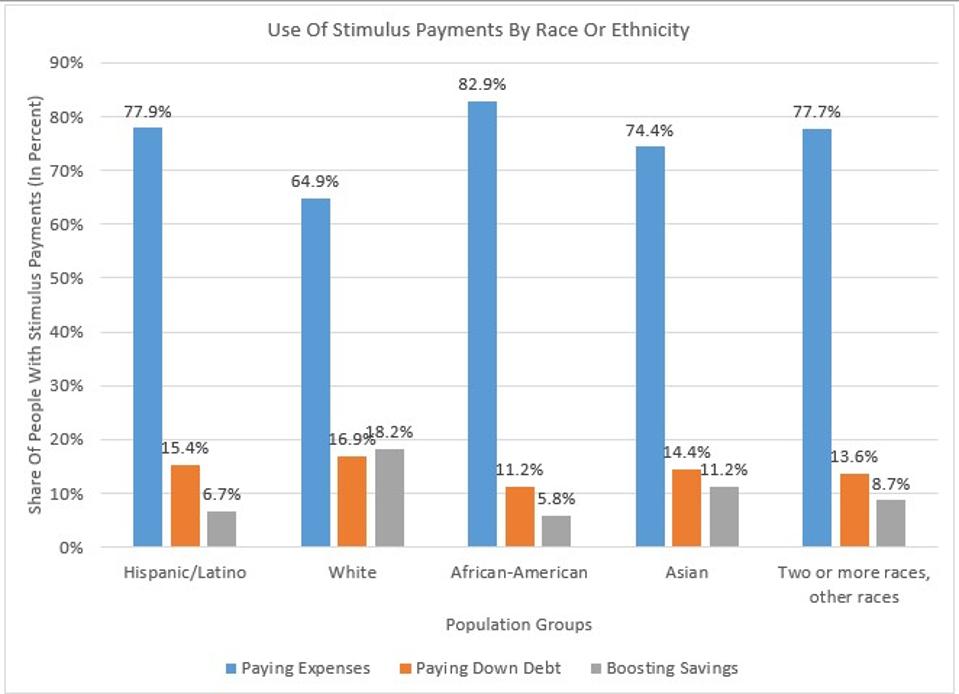

Similarly, there are some key differences in the use of money by race and ethnicity. A high of 82.9% of African-Americans said that they will use their stimulus payments to pay for things like groceries, utilities and personal care items, the three largest spending uses of stimulus checks (see figure below). Still almost two-thirds, 64.9% of white respondents indicated that they will use the stimulus money to cover expense. The stimulus payments play their expected role as emergency funds when job and income losses mount.

Using Stimulus Money To Pay Down Debt Or Boost Savings Varies By Race And Ethnicity

CALCULATIONS BASED ON U.S. CENSUS. HOUSEHOLD PULSE SURVEY.

The flip side, though, is that there is a substantial gap by income, race and ethnicity in using these funds to build up more savings that could be used for future emergencies. People, who did not use or intend to use their stimulus checks for expenses, could either pay down their debt or boost their savings. The share of whites who planned on using their stimulus to increase their wealth was more than twice as high with 35.1% as that of African-Americans with 17.1% (see figure above). White families were thus more likely to use their stimulus money to build a cushion for future unexpected spending needs, for instance, due to prolonged spells of unemployment than was the case for non-white or Latinx families.

The data illustrate the need for additional stimulus help as the deep recession with double-digit unemployment rates continues. In the short run, the checks mainly did what they were supposed to do: help struggling families pay their bills. They worked to stave off even more economic pain, especially among non-white or Latinx families as my colleague Connor Maxwell has detailed. The first round of checks was also enough for about half of high-income households and more than a third of white families to create additional wiggle room for future emergencies. This was the case for far smaller shares of lower-income and non-white or Latinx families. Yet, those are often the families that struggle the most from high unemployment and food insufficiency. They also have much smaller emergency saving than higher-income families and whites do. Another round of government support for hard-hit families is sorely and quickly needed to avoid massive increases in racial economic inequality.