By: Joshua Preiss

See original post here.

Universal basic income is an idea usually associated with the political left. However, it also has surprising support from the Libertarian right in the form of Milton Friedman’s negative income tax. Indeed, Friedman’s case for NITs gets to the core of his case for free markets, freedom from coercion, and where government should intervene in our economies, writes Joshua Preiss.

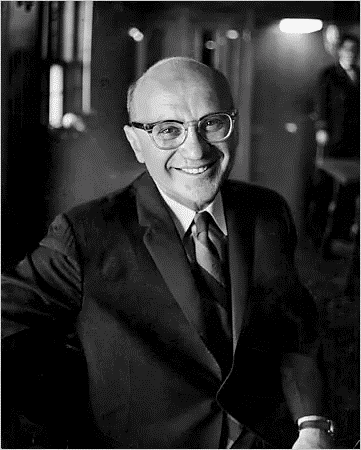

After John Maynard Keynes, Milton Friedman is arguably the most influential economist of the 20th Century. Like Keynes, his influence extends far beyond technical questions in economics. Friedman is known as a champion of small government who provided key talking points for Reaganomics, a political philosophy that in the public imagination is best captured by Reagan’s iconic declaration that “government is not the solution to our problem, government is the problem.” It may therefore come as a surprise that Friedman proposed a massive, government policy to alleviate poverty.

This policy is a negative income tax (NIT). While the mechanism for distribution (and therefore the politics) may differ from other forms of universal basic income (UBI), NIT also functions as an income floor for all families. Friedman’s plan would work through the existing income tax system. In practice, NIT is the standard deduction in reverse. For families whose earnings are below the relevant threshold, they would simply file an estimated earnings return (like those self-employed) and receive regular payments (say bi-weekly) over the year totaling 50 cents for every dollar their income is below the threshold. This government top-up ensures that their income never drops below a set amount.

The rationale for only making up 50% of the difference is to provide workers with the incentive to earn more income, rather than effectively taking every dollar that they earn back in taxes. To eliminate poverty, the NIT threshold would need to be set well above the 2023 standard deduction of $27,700 for a family of four.

Friedman argues that NIT is both more efficient and more consistent with individual liberty than the existing welfare state.

By replacing a myriad of federal agencies tasked with some form of poverty relief, NIT eliminates an enormous, complex, costly, and ever-expanding government bureaucracy. It also provides workers with incentive to work. The result, he argues, would almost certainly to lower the tax burden. By contrast with subsidies to certain workers, and programs that provide in-kind benefits, Friedman argues that NIT meets the basic needs of the poor without distorting the role that the price mechanism plays in efficiently allocating resources. It does so because it leaves recipients free to choose how and what to spend the money on. Under the existing system, by contrast, Friedman writes (endorsing a view he attributes to Herbert Kronsey):

“The people whose freedom is really being interfered with are the poor… A government official tells them how much to spend on food, rent, and clothing. They have to get permission from an official to rent a different apartment or secondhand furniture. Mother’s receiving aid for dependent children may have their male visitors checked on by government investigators at any hour of the day. They are the people who are deprived of personal liberty, freedom, and dignity.”

In response to prominent conservatives like William F. Buckley, who argue that there will always be a subset of “disorganized poor” who possess no desire to work and can’t be trusted to care for themselves or their families, Friedman counters that the last thing we should want is to create more government agents and agencies to “police” or “spy on” their fellow Americans. It’s degrading, inefficient, and a threat to liberty. Free people shouldn’t be expected to tolerate such treatment. While taxation is a form of coercion (on Friedman’s view) society needs to recognize and treat with dignity those who confront poverty. In his view, NIT (ideally complemented by robust private charity) meets this need most effectively. A central virtue of his proposal, he continues, would be equity: NIT “treats rich people and poor people the same.”

Markets enable cooperation without coercion

[It is worth noting that Buckley’s argument, which foreshadows decades of American welfare politics and policy, is prefaced on the condition that society is operating at full employment. In societies and regions with persistent or chronic unemployment, the conservative argument fails on its own terms].

Friedman should take the freedom argument further. NIT is essential for him to redeem a central tenet of his political philosophy: markets enable cooperation without coercion. To defend this claim, he asks the reader to imagine a simple market model where each household controls resources that enable it to provide indispensable goods and services either for itself or for exchange. “Since each household always has the alternative of producing directly for itself,” he writes in Capitalism and Freedom, “it need not enter into any exchange… cooperation is thereby achieved without coercion.” Here, Friedman is more or less adopting the economic core of Jeffersonian republicanism: freedom comes from economic independence, the ability to produce all you need for yourself and your family. Unlike wage-earners who lack this independence, Jefferson argues, free citizens are not subject to the will and whim of employers. This philosophy provides a central justification for the Louisiana Purchase and, half a century later the Homestead Act. For republicans, the diffusion of productive capital (and economic power) is critical to a free republic.

That Friedman’s argument recalls Jeffersonian republicanism is not surprising. In his later work Free to Choose he frequently invokes Jefferson in support of his proposals. What is surprising is that Friedman draws precisely the opposite conclusion from this example. Just as in the simple model, Friedman continues,

“in the complex enterprise and money-exchange economy, cooperation is strictly individual and voluntary provided: (1) that enterprises are private, so that the ultimate contracting parties are individuals and (2) that individuals are effectively free to enter or not enter into any particular exchange, so that every transaction is strictly voluntary.”

Notice the change from a simple to a complex economy. In the former, it is access to productive resources, and therefore the ability to produce for yourself, that made market exchange free or non-coercive. In the latter, Friedman suggests that simply being free to decline a particular exchange will do. What is missing, in short, is the widespread access to productive resources and economic power that republicans from Jefferson to Abraham Lincoln understood as essential for workers to claim the status of free citizens.

Fortunately for Friedman and like-minded libertarians, NIT can help fill this gap; provided the threshold is both (1) substantial, enabling workers to not only escape poverty but achieve a decent quality of life for themselves and their families and (2) not conditioned on their ongoing search for employment. As in the simple model, workers will not only be able to decline a particular employment contract. They will also be free to not take orders from any of their fellow citizens. If a more egalitarian distribution of productive resources is neither feasible nor desirable, NIT can take the place of these resources in one crucial respect: it can give workers the freedom to say no.

F.A. Hayek, another champion of the free market, also defends a government-funded economic floor for all citizens and their families. Hayek’s endorsement of UBI is best understood in the language of republicanism. In The Constitution of Liberty, Hayek contrasts being free with being “subject to the will of another.” UBI furthers individual freedom by ensuring that they always have a quality alternative to subjugation, even if the local or national economy fails to afford them a wide range of quality employment opportunities, or they lack the skills or mobility to command such employment.

While in the past I’ve criticized aspects of Hayekian political economy and other forms of free-market or commercial republicanism, one of their great virtues is that they don’t treat economic freedom as simply or fundamentally a matter of freedom of choice in the marketplace. What commercial republicans recognize is that just as state actors pose a significant threat to economic freedom, freedom depends on public policy in ways beyond the mere (but crucial) protection of person and property. For example, center-right republican Robert Taylor argues that these policies should include vigilant use of anti-trust, relocation assistance, “capitalist demogrants” to provide capital for people to start businesses, and UBI.

Conservatives, republicans, and libertarians that take domination seriously, in short, understand the need for a bit of “big government”

Commercial republicans have reason to see “closed-shop” unionism as a potential threat to liberty. As Taylor notes, however, absent policies that lower the cost of exit by providing workers with a wide range of quality alternatives, and the resources to take advantage of them, “right-to-work” legislation and other policies that weaker worker power will on the whole diminish rather than further freedom. His critique of labor unions depends on government playing its limited but essential role effectively. Conservatives, republicans, and libertarians that take domination seriously, in short, understand the need for a bit of “big government.”

My claim is not that Friedman is best understood as a commercial republican. Instead, I argue that without NIT securely in place, many proposals to shrink the size of government, on Friedman’s own reasoning, make millions of Americans less free. Indeed, Friedman’s argument that economic freedom is necessary for political freedom – the foundation of Capitalism and Freedom – depends on the ability of a complex economy to provide citizens with a wide range of valuable alternatives to their present employer. NIT ensures that they always have one. Friedman’s endorsement of NIT is neither aberrative nor regrettable. It is essential to his case for free markets.