Garry Kasparov is perhaps the greatest chess player in history. For almost two decades after becoming world champion in 1985, he dominated the game with a ferocious style of play and an equally ferocious swagger.

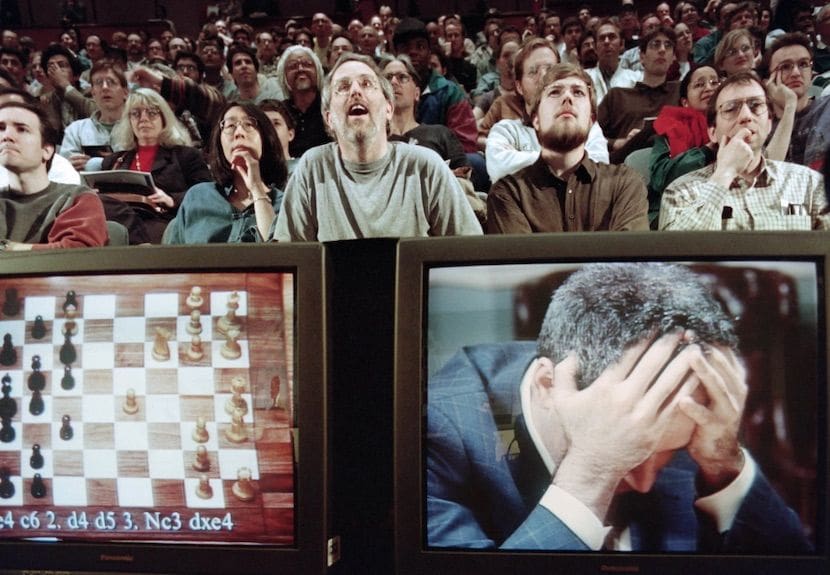

Outside the chess world, however, Kasparov is best known for losing to a machine. In 1997, at the height of his powers, Kasparov was crushed and cowed by an IBM supercomputer called Deep Blue. The loss sent shock waves across the world, and seemed to herald a new era of machine mastery over man.

The years since have put things into perspective. Personal computers have grown vastly more powerful, with smartphones now capable of running chess engines as powerful as Deep Blue alongside other apps. More significantly, thanks to recent progress in artificial intelligence, machines are learning and exploring the game for themselves.

Deep Blue followed hand-coded rules for playing chess. By contrast, AlphaZero, a program revealed by the Alphabet subsidiary DeepMind in 2017, taught itself to play the game at a grandmaster level simply by practicing over and over. Most remarkably, AlphaZero uncovered new approaches to the game that dazzled chess experts.

Last week, Kasparov returned to the scene of his famous Deep Blue defeat—the ballroom of a New York hotel—for a debate with AI experts organized by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence. He met with WIRED senior writer Will Knight there to discuss chess, AI, and a strategy for staying a step ahead of machines. An edited transcript follows:

WIRED: What was it like to return to the venue where you lost to Deep Blue?

Garry Kasparov: I’ve made my peace with it. At the end of the day, the match was not a curse but a blessing, because I was a part of something very important. Twenty-two years ago, I would have thought differently. But things happen. We all make mistakes. We lose. What’s important is how we deal with our mistakes, with negative experience.

1997 was an unpleasant experience, but it helped me understand the future of human-machine collaboration. We thought we were unbeatable, at chess, Go, shogi. All these games, they have been gradually pushed to the side [by increasingly powerful AI programs]. But it doesn’t mean that life is over. We have to find out how we can turn it to our advantage.

I always say I was the first knowledge worker whose job was threatened by a machine. But that helps me to communicate a message back to the public. Because, you know, nobody can suspect me of being pro-computers.

What message do you want to give people about the impact of AI?

I think it’s important that people recognize the element of inevitability. When I hear outcry that AI is rushing in and destroying our lives, that it’s so fast, I say no, no, it’s too slow.

“I always say I was the first knowledge worker whose job was threatened by a machine.”

GARRY KASPAROV

Every technology destroys jobs before creating jobs. When you look at the statistics, only 4 percent of jobs in the US require human creativity. That means 96 percent of jobs, I call them zombie jobs. They’re dead, they just don’t know it.

For several decades we have been training people to act like computers, and now we are complaining that these jobs are in danger. Of course they are. We have to look for opportunities to create jobs that will emphasize our strengths. Technology is the main reason why so many of us are still alive to complain about technology. It’s a coin with two sides. I think it’s important that, instead of complaining, we look at how we can move forward faster.

When these jobs start disappearing, we need new industries, we need to build foundations that will help. Maybe it’s universal basic income, but we need to create a financial cushion for those who are left behind. Right now it’s a very defensive reaction, whether it comes from the general public or from big CEOs who are looking at AI and saying it can improve the bottom line but it’s a black box. I think it’s we still struggling to understand how AI will fit in.

A lot of people will have to contend with AI taking over some part of their jobs. What advice do you have for them?

There are different machines, and it is the role of a human and understand exactly what this machine will need to do its best. At the end of the day it’s about combination. For instance, look at radiology. If you have a powerful AI system, I’d rather have an experienced nurse than a top-notch professor [use it]. A person with decent knowledge will understand that he or she must add only a little bit. But a big star in medicine will like to challenge the machines, and that destroys the communication.

People ask me, “What can you do to assist another chess engine against AlphaZero?” I can look at AlphaZero’s games and understand the potential weaknesses. And I believe it has made some inaccurate evaluations, which is natural. For example, it values bishop over knight. It sees over 60 million games that statistically, you know, the bishop was dominant in many more games. So I think it added too much advantage to bishop in terms of numbers. So what you should do, you should try to get your engine to a position where AlphaZero will make inevitable mistakes [based on this inaccuracy]

“Technology is the main reason why so many of us are still alive to complain about technology.”

GARRY KASPAROV

I often use this example. Imagine you have a very powerful gun, a rifle that can shoot a target 1 mile from where you are. Now a 1-millimeter change in the direction could end up with a 10-meter difference a mile away. Because the gun is so powerful, a tiny shift can actually make a big difference. And that’s the future of human-machine collaboration.

With AlphaZero and future machines, I describe the human role as being shepherds. You just have to nudge the flock of intelligent algorithms. Just basically push them in one direction or another, and they will do the rest of the job. You put the right machine in the right space to do the right task.

How much progress do you think we’ve made toward human-level AI?

We don’t know exactly what intelligence is. Even the best computer experts, the people on the cutting edge of computer science, they still have doubts about exactly what we’re doing.

What we understand today is AI is still a tool. We are comfortable with machines making us faster and stronger, but smarter? It’s some sort of human fear. At the same time, what’s the difference? We have always invented machines that help us to augment different qualities. And I think AI is just a great tool to achieve something that was impossible 10, 20 years ago.

How it will develop I don’t know. But I don’t believe in AGI [artificial general intelligence]. I don’t believe that machines are capable of transferring knowledge from one open-ended system to another. So machines will be dominant in the closed systems, whether it’s games, or any other world designed by humans.

David Silver [the creator of AlphaZero] hasn’t answered my question about whether machines can set up their own goals. He talks about subgoals, but that’s not the same. That’s a certain gap in his definition of intelligence. We set up goals and look for ways to achieve them. A machine can only do the second part.

So far, we see very little evidence that machines can actually operate outside of these terms, which is clearly a sign of human intelligence. Let’s say you accumulated knowledge in one game. Can it transfer this knowledge to another game, which might be similar but not the same? Humans can. With computers, in most cases you have to start from scratch.

Let’s talk about the ethics of AI. What do you think of the way the technology is being used for surveillance or weapons?

We know from history that progress cannot be stopped. So we have certain things we cannot prevent. If you [completely] restrict it in Europe, or America, it will just give an advantage to the Chinese. [But] I think we do need to exercise more public control over Facebook, Google, and other companies that generate so much data.

People say, oh, we need to make ethical AI. What nonsense. Humans still have the monopoly on evil. The problem is not AI. The problem is humans using new technologies to harm other humans.

AlphaZero “values bishop over knight. I think it added too much advantage to bishop in terms of numbers.”

GARRY KASPAROV

AI is like a mirror, it amplifies both good and bad. We have to actually look and just understand how we can fix it, not say “Oh, we can create AI that will be better than us.” We are somehow stuck between two extremes. It’s not a magic wand or Terminator. It’s not a harbinger of utopia or dystopia. It’s a tool. Yes, it’s a unique tool because it can augment our minds, but it’s a tool. And unfortunately we have enough political problems, both inside and outside the free world, that could be made much worse by the wrong use of AI.

Returning to chess, what do you make of AlphaZero’s style of play?

I looked at its games, and I wrote about them in an article that mentioned chess as the “drosophila of reasoning.” Every computer player is now too strong for humans. But we actually could learn more about our games. I can see how the millions of games played by AlphaGo during practice can generate certain knowledge that’s useful.

It was a mistake to think that if we develop very powerful chess machines, the game would be dull, that there will be many draws, maneuvers, or a game will be 1,800, 1,900 moves and nobody can break through. AlphaZero is totally the opposite. For me it was complementary, because it played more like Kasparov than Karpov! It found that it could actually sacrifice material for aggressive action. It’s not creative, it just sees the pattern, the odds. But this actually makes chess more aggressive, more attractive.

Magnus Carlsen [the current World Chess Champion] has said that he studied AlphaZero games, and he discovered certain elements of the game, certain connections. He could have thought about a move, but never dared to actually consider it; now we all know it works.

When you lost to DeepBlue, some people thought chess would no longer be interesting. Why do you think people are still interested in Carlsen?

You answered the question. We are still interested in people. Cars move faster than humans, but so what? The element of human competition is still there, because we want to know that our team, our guy, he or she is the best in the world.

The fact is that you have computers that dominate the game. It creates a sense of uneasiness, but on the other hand, it has expanded interest in chess. It’s not like 30 years ago, when Kasparov plays Karpov, and nobody dared criticize us even if we made a blunder. Now you can look at the screen and the machine tells you what’s happening. So somehow machines brought many people into the game. They can follow, it’s not a language they don’t understand. AI is like an interface, an interpreter.