Chicago Alderman Ameya Pawar is worried about the future.

He is concerned that a coming wave of automation could put millions of people out of work and result in more extreme politics.

Pointing to investments in autonomous vehicles by companies like Tesla, Amazon, and Uber, Pawar observed that long-haul trucking jobs, historically a source of middle-class employment, may become obsolete. More people out of work means more political polarization, says Pawar.”We have to start talking about race and class and geography, but also start talking about the future of work as it relates to automation. All of this stuff is intertwined.”

Before leaving the race after being outspent by two billionaire candidates, Pawar campaigned for the Illinois Democratic Party’s nomination for governor. One of the themes of his candidacy was that politicians were scapegoating various racial or ethnic groups for their constituents’ material problems.

“You know, the British pit Hindus and Muslims against one another,” Pawar told The Intercept at the time, drawing on his Indian-American heritage. “Pit people against one another based on class and geography, caste … this is no different. Chicago versus downstate. Downstate versus Chicago. Black, white, brown against one another. All poor people fighting over scraps.”

Pawar now believes that a wave of mass automation will only compound this problem.

“From a race and class perspective, just know that 66 percent of long-haul truck drivers are middle-aged white men,” he observed. “So if you put them out of work without any investment in new jobs or in a social support system so that they transition from their job to another job, these race and class and geographical divides are going to grow.”

Pawar thinks that one way to battle racial resentment is to address the economic precocity that politicians have used to stoke it. He has decided to endorse the universal basic income — an idea that has been picking up steam across the world.

The UBI is based on a simple premise: People don’t have enough money to provide for their essential needs, so why not just give them more?

UBI schemes entail giving a standard cash grant to everyone — regardless of need. Traditionally, the United States has addressed poverty by delivering in-kind goods. For instance, the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, formerly known as the food stamp program, issues electronic cards that can be used to purchase certain types of food.

But some economists have countered that simply giving people money is more beneficial.

Research shows that cash transfer programs are more efficient overall, as they sidestep the administrative costs of distributing in-kind goods. The theory is that people know their own needs and can allocate money more effectively than the government. Moreover, the hope is that because UBI is a universal initiative, it will avoid some of the stigma associated with need-based programs, which have historically been criticized as handouts to the “undeserving” poor.

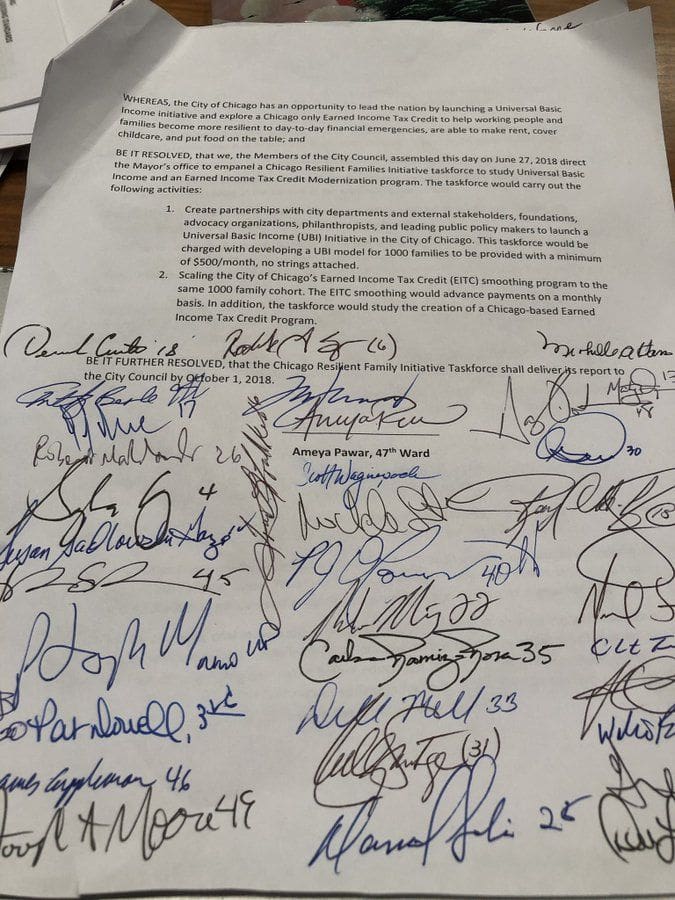

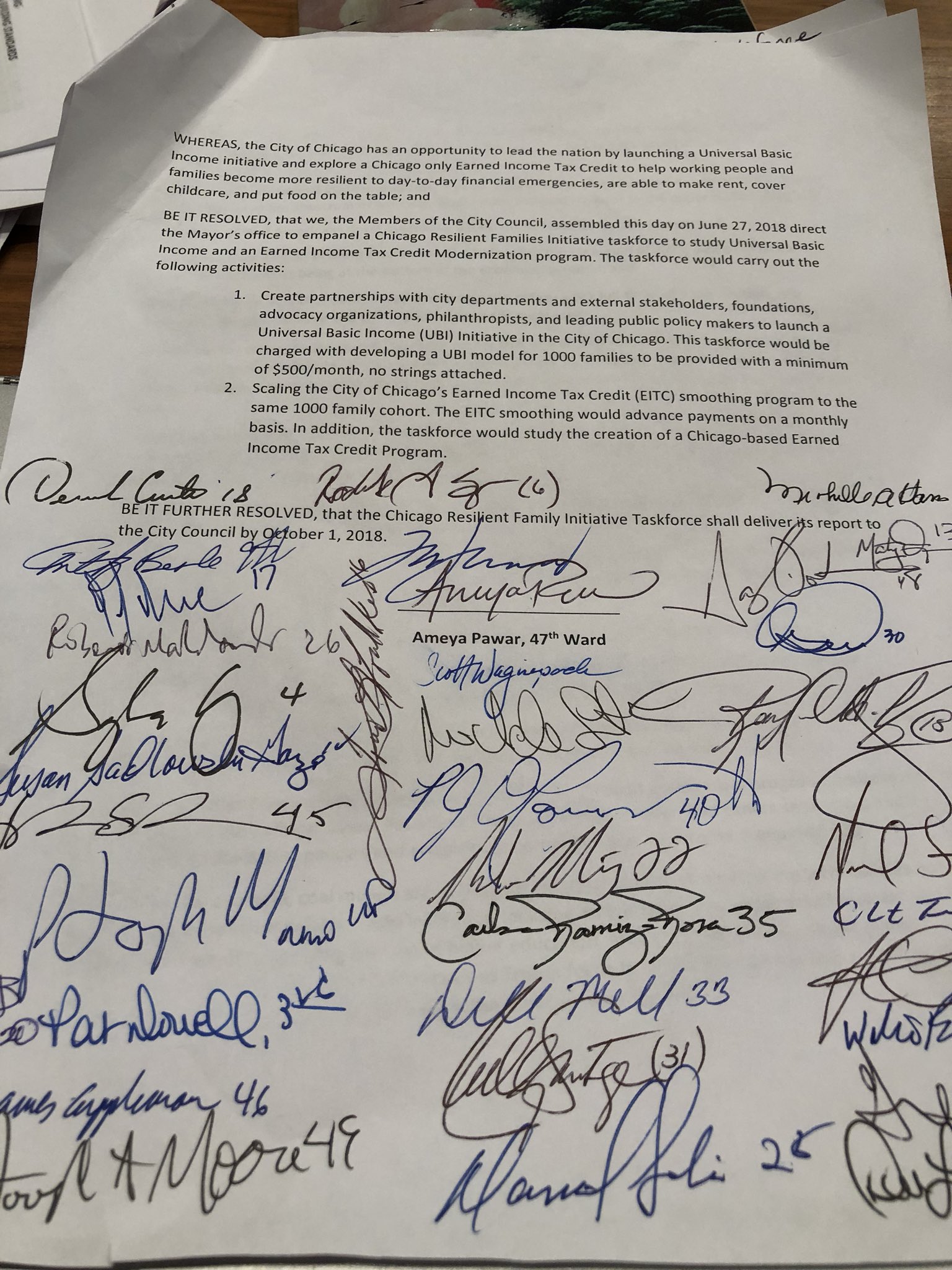

Pawar recently introduced a pilot for a UBI program in Chicago. Under his program, $500 a month would be delivered to 1,000 Chicago families — no strings attached. Additionally, the proposal would modify the Earned Income Tax Credit program for the same 1,000 families, so they’d receive payments on a monthly basis instead at the end of the year — a process known as “smoothing” that enables families to integrate the tax credit into their monthly budgets.

The proposal also leaves room for the creation of a Chicago-specific EITC program.

Pawar has convinced the majority of Chicago lawmakers to co-sponsor the plan, and he is hoping that the Chicago City Council will soon work with the mayor to implement it.

“Nearly 70 percent of Americans don’t have $1,000 in the bank for an emergency,” Pawar told The Intercept. “UBI could be an incredible benefit for people who are working and are having a tough time making ends meet or putting food on the table at the end of the month. … It’s time to start thinking about direct cash transfers to people so that they can start making plans about how they’re going to get by.”

Simply giving people money so they can cover their expenses seems like a radical idea — especially in America, where individualism and personal responsibility are considered chief virtues, and the notion of getting something for nothing is scorned. But there’s an easy rejoinder — at least to those skeptics who doubt UBI because they think the money will be squandered on nonessential goods. UBI-style direct cash transfers have been implemented elsewhere. And they work.

One of the most effective anti-poverty programs in the 21st century is Brazil’s Programa Bolsa Familia. Deborah Wetzel, a senior staffer at the World Bank, called the program a “quiet revolution,” noting that PBF “has been key to help Brazil more than halve its extreme poverty — from 9.7 to 4.3 percent of the population.” Moreover, the program also helped to shrink income inequality by about 15 percent, says Wetzel. One studyby the Inter-American Development Bank noted that the program cost about 0.5 percent of the gross domestic product of Brazil, but was credited with reducing the infant mortality rate caused by undernourishment and diarrhea by more than 50 percent.

PBF is not a universal program, as payments go only to Brazilians living below a certain wage threshold. (In 2013, about one quarter of Brazilians received this benefit). Another key difference is that unlike PBF, which requires that children of recipient families attend school and regularly visit the doctor, UBI is unconditional. But PBF is a useful model for UBI, as both are direct cash transfer programs.

The best domestic example of UBI can be found in Alaska. Since 1976, Alaska’s state government has maintained the Alaska Permanent Fund, which invests in financial assets like public and private equities, real estate, and infrastructure to generate revenues for the state government. The fund, which is also fed by residuals on oil from public lands, then issues a check every year to every resident of Alaska. In 2017,that payment amounted to $1,100.

Back in the continental United States, the 27-year-old mayor of Stockton, California, Michael Tubbs, started rolling outa local UBI pilot program earlier this year. The Stockton program, which is being implemented in partnership with Facebook co-founder Chris Hughes’s Economic Security Project, will provide $500 monthly to 100 families. The 18-month study will start in 2019.

In an interview with Politico, Tubbs rejected the argument that paying people for doing nothing is inherently undignified.

“There’s this interesting conversation we’ve been having about the value of work,” he said. “Work does have some value and some dignity, but I don’t think working 14 hours and not being able to pay your bills, or working two jobs and not being able — there’s nothing inherently dignified about that.”

If Pawar’s program is implemented by Mayor Rahm Emanuel, Chicago would be the largest city in America to experiment with UBI. Matt Bruenig, the founder of the People’s Policy Project and a UBI advocate, is skeptical that a municipality can run a successful UBI because cities tend to have limited capacity to collect revenue. However, he does think that the pilot project has merit.

“This looks like a UBI pilot program, which is a good idea, just to study its effects and produce data that can help guide other UBI efforts,” he told The Intercept.

“Our hope, that I know will be born out in this pilot, is that it will show that when we smooth out the EITC, and we provide a monthly basic income to 1,000 families, that they will be able to plan for expenses, they can make decisions about savings, they can make decisions about investing, they could make decisions about how they could deal with a financial emergency, just like all families do,” Pawar told us. “And once implemented, we’ll be able to hopefully scale it.”

To the alderman, the question is not so much whether the country can afford to implement UBI so much as whether it can afford not to.

“My response to Amazon, and Tesla, and Ford, and Uber … we need to start having a conversation about automation and a regulatory framework so that if jobs simply go away, what are we going to do with the workforce? … If [those companies are] reticent to pay their fair share in taxes and still want tax incentives and at the same time automate jobs, what do you think is going to happen?” Pawar asked. “These divisions are going to grow and, in many ways, we’re sitting on a powder keg.”