By Pat Kane

See original post here.

WHEN speaking on BBC Scotland’s excellent Debate Night show on Wednesday, I was lobbed a perfectly formed audience question. It was so appropriate I felt like Robert Redford in The Natural, ready to smash the ball into the floodlights.

I kinda missed, expectedly. But here was the question: Can Scotland influence the opportunities and threats posed by artificial intelligence (AI) – or are we essentially just bystanders? And was I pessimistic or optimistic about AI?

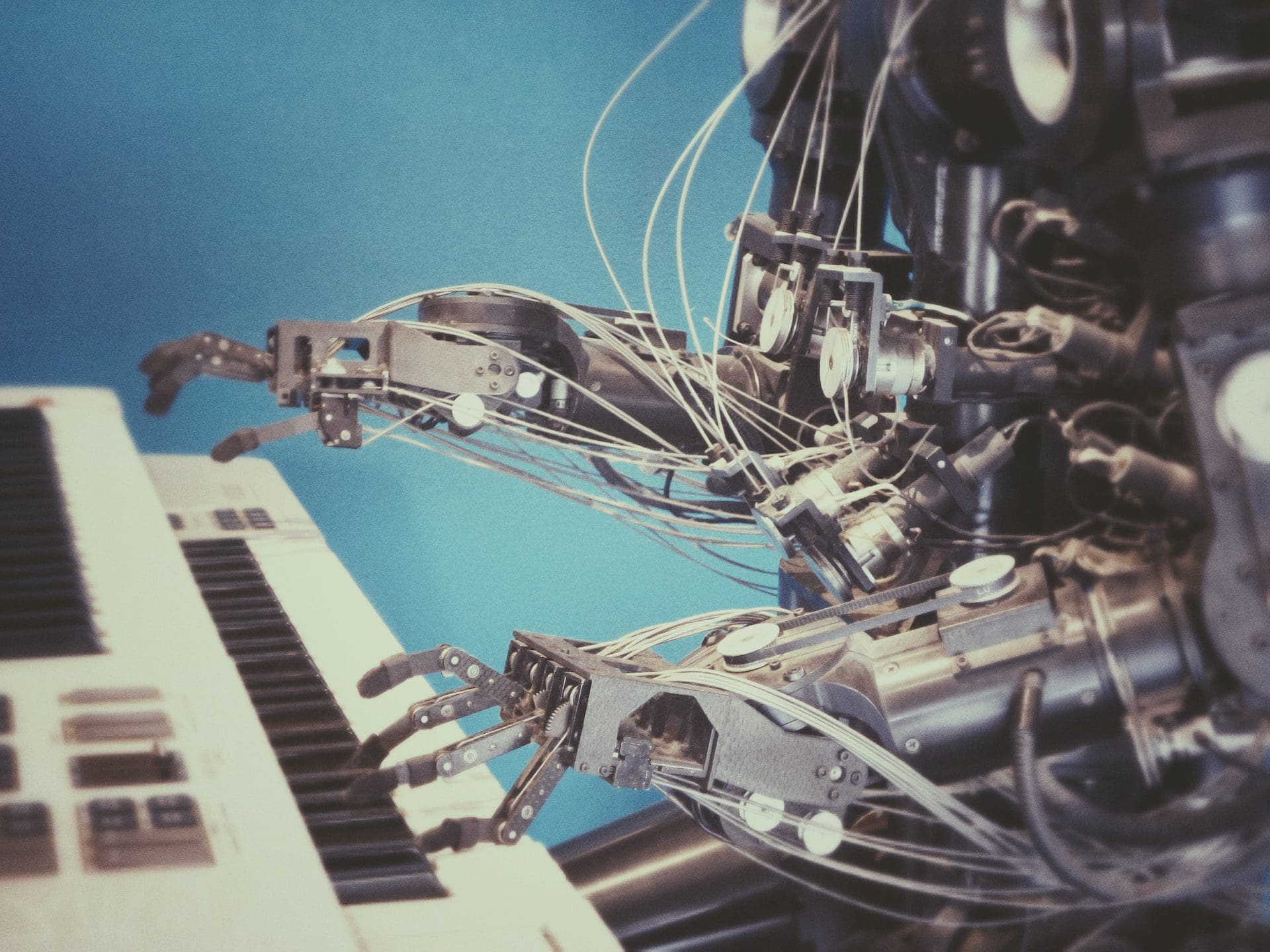

Here, a bit tidied up, is my reply: “I’ve been dreaming of this moment most of my adult life. Musicians (like me) love technology – we make it do beautiful things, we’re not alienated by it. And the artistic life is upon us all, ladies and gentlemen – if we use these machines properly.

“What’s interesting about AI is that it takes what the anarchist thinker David Graeber called ‘bullshit’ jobs – routinised jobs that seem to have no purpose or meaning – and puts them most in danger.

“And humans at either end of the spectrum – whether you want to be purely expressive on one extreme, or you want to be hands-on with care and craft at the other – these are the people who will survive this moment. It’s potentially a time of great liberation.

“What can Scotland do in relation to AI? Well, with the powers of independence – which means jurisdiction over your institutions, your labour and welfare laws – we can look at these technologies and say: How long should a working week be?

“Rather than the profits going to the corporations that are bringing these technologies into our lives, we can say: Why couldn’t some of these revenues fund universal basic services, universal basic income? This is a time of great liberation – if the citizens can rise up and seize it.

“And if Scotland gets the nation-state capacity to build the institutions that ride this future – and choose to be part of, say, the EU’s fantastically detailed regulation of AI – we’ll be in the driving seat.”

There endeth the sermon. I reproduce my response here because, out of the usual panic before the television camera, it actually comes from a very authentic place. Which doesn’t mean to say I can’t see the flaws and gaps in my argumentation.

It’s true to say I have been waiting for superintelligent AI to come along all my life. However, I’m not deaf to the charge that this might be a God-replacement fantasy.

My rejection of the Catholic religion during my Higher exams (it’s my efforts that will get me there, not His!) came at the same time as I was lost in the sci-fi classics – Isaac Asimov, Robert Heinlein, Ray Bradbury, Philip K Dick. As well as the rougher narratives in British sci-fi comics such as 2000 AD, Warrior, and Crisis.

Like the aliens in these stories, I was actively looking for robots and AI to present a profound challenge to human nature. A nature which, as manifested in the reactive, cut-down-the-tall-poppy environment of school (and Coatbridge) that I was growing up in, I wasn’t that impressed with.

I am currently (and happily) using the AI chatbot GPT-4 nearly every other day, and I think this early conditioning of mine explains why.

Here I sit, with a calm, polite, not shouty, not abusive conversation partner. Unfazed by almost any cultural or intellectual reference I bring to it, GPT-4 unfailingly reacts in a steady and constructive manner. What a relief, just as I always dreamed someone/something would.

The musicians with technology point, I’d reinforce. Drummers have been faced with drum machines; physical studios with virtual versions of the great recording rooms; singers with their vocals digitally nudged into perfection.

Yet “playing around” with tech, subjecting it to human whims and experiences, means that musicians come up with hybrid forms of smart tech.

For example, they’ll use many shades of “generative” tech – from complete simulation to none at all – in order to generate an unprecedented thrill in themselves and their listeners.

UNTIL we get lovelorn or rebellious AI, with insatiable appetites and sensual drives, I doubt the humans will be kicked out of music anytime soon. Indeed, we should look to artists as an example of how we can best draw the line – and it’s a wavy, fuzzy one – between the human and the machine.

And “bullshit jobs”? Chatbots passing high-end legal and medical exams with honours is spectacular. But think for a minute what that means for you if your job is based on having ingested lots of bureaucratic and organisational precedent, which you then assess and regurgitate on request.

At the very least, the possibility of nine out of 10 of those jobs disappearing – with the remainder in a supervisory role – is real, according to several assessments.

The AI godfather Stuart Russell, who I engaged with at his Reith Lecture in Edinburgh a few years ago, is behind my point about the consequences of routine organisational labour being automated. Freely creative minds, and hands-on care and craft, will both be given new impetus, Russell predicted.

On the question of the political economy of AI – the institutions and regulations that will transition humans into a future not defined by the work ethic – I do think we have the best chance of building those under conditions of independence.

Professor Shannon Vallor, director of the Centre for Technomoral Futures at the University of Edinburgh, gave me a quote on Scotland’s leadership in this area.

“The Scottish Government is in a particularly strong position to model this pragmatic, grounded approach; it pioneered an AI strategy in 2021 focused on trustworthy, ethical and inclusive AI innovation that serves the wider public interest, rather than AI for AI’s sake”, she writes.

“We need to bring AI and political leaders back to earth to craft evidence-based and practical AI governance strategies that keep our interests at the centre.”

“So I think as the debate unfolds about how the UK, EU, USA and other governance bodies globally should respond to AI, Scotland should not only move forward with implementing its own strategy, which is very well suited for this moment, but seek to shape the debate internationally about AI governance priorities.”

I’d also recommend watching the Trustworthy, Ethical and Inclusive Artificial Intelligence MSP debate on the Scottish Parliament website.

If you want the opposite of Sam Altman and Elon Musk touring the conference halls – whipping up fears in order to present themselves as the lead assuagers of those fears – this debate was it.

But the calm intelligence on display in the Holyrood chamber models, for me, how I want these AIs to be in my own life. I want them as amplifiers of my strengths and visions.

As the philosopher Roberto Mangabeira Unger puts it: “These machines do what’s repeatable, so that I can do what humans do – the unrepeatable.”

The problem is how to instil a sense of agency in people – a belief that such an advanced human civilisation is really possible, by means of the ethical use and arrangement of this tech.

Thus my gesticulations, and wild metaphors, on a Wednesday night telly debate.

Sorry/not sorry.